Rasquiña’s revolution: How the Choneros took control of Ecuador’s prisons.

It took Ecuador’s police nine months to track down the country’s most wanted fugitive. But when they found him outside an apartment complex in Bogotá, Colombia, the leader of the Choneros gang, Jorge Luis Zambrano, better known as “Rasquiña,” or simply “JL,” seemed calm.

As a police video released to the media later showed, Rasquiña – dressed in a polo shirt and sporting a slick-back hairstyle – looked completely unsurprised, reported by insightcrime.

“You made me walk a long way,” the arresting officer tells him as he pushes him to the floor and handcuffs him.

Rasquiña laughs. “You took your time,” he says.

hat brief moment marked a turning point in the evolution of Ecuadorian organized crime. And it would prove the catalyst for the criminal takeover of the nation’s prison system.

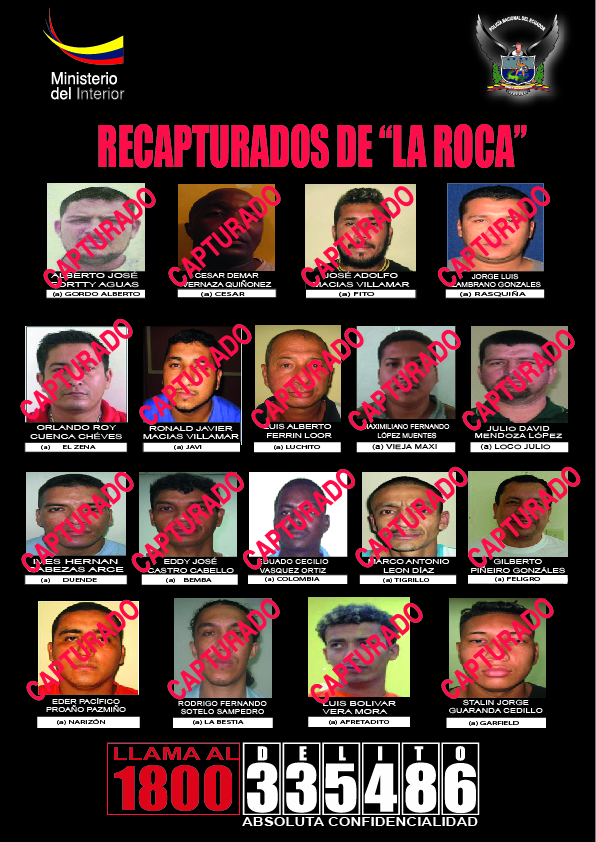

Rasquiña had escaped along with 17 other inmates from the La Roca prison under cover of Carnival festivities on the night of February 11, 2013. When the police entered La Roca that night, they found 14 guards handcuffed and locked in cells. A fence had been cut several days before, and footprints led to a nearby riverbank where they found a boat containing prison guard uniforms, munitions, and rifle magazines.

For the government of President Rafael Correa, it was a humiliation. Inaugurated just three years earlier, La Roca was a central pillar of Correa’s planned overhaul of the prisons. As a high security, or what is often called supermax, prison, it was the hardline counterweight to his progressive plans for a more humane system based on rehabilitation. But the escape exposed a painful reality, an early sign of what would become a central characteristic of Correa’s prison reforms: They were failing.

When police investigated, they found the prisoners had not masterminded an impossible escape from an Alcatraz-style fortress. They had broken out of a facility where many of the lights were out, the doors did not lock, the cameras and X-ray machines did not work, and the external electrical fence was disconnected. They had coordinated their plans with accomplices on the outside with contraband cell phones and launched their assault with smuggled weapons. And, authorities would come to believe, they did it all with the complicity of guards and police.

The dysfunction on display in the La Roca jailbreak was symptomatic of the broader institutional weaknesses and endemic corruption that was eating away at Ecuador’s prison system. But the state’s failings had created criminal opportunities, and the recaptured Rasquiña, with his dreams of escaping jail crushed, was now poised to take advantage.

Although there was little in his record to suggest it, Rasquiña was a criminal visionary. Within a matter of years, he would lead the Choneros in a bid to take over the prison system. And his driving ambition would turn the streets into a bloody mirror of its penitentiaries, tipping Ecuador into a security spiral that a decade later would see the president declare an “internal armed conflict” with “terrorist” groups.

An Education in Organized Crime

Rasquiña was born in Manta, a port city in the central province of Manabí. There, as a young man, he met two people who would change the trajectory of his life: Jorge Bismarck Véliz España, a.k.a. “Teniente España,” an up-and-coming criminal from the nearby town of Chone, and José Adolfo Macías Villamar, alias “Fito,” a chubby, boyish-faced friend who played sports with Rasquiña. The first would draw Rasquiña into the world of organized crime. The second would become his partner and, later, Ecuador’s most wanted criminal.

In Chone, Teniente España led a gang that had progressed from robberies into extortion, microtrafficking, kidnapping, and assassinations. As they expanded into Manta, they became known as the Choneros, a nod to their hometown. But even as their infamy spread locally, there was little clue to what they would become.

“The Choneros organization was not so notable at that time. It was a sort of group of people involved in criminal activities, but it didn’t have the magnitude or the grand scale that it has now,” said a local Choneros commander, who spoke to InSight Crime on condition of anonymity.

It was 2005, when the Choneros first entered the wider public conscious. A rival group, the Queseros, ambushed Teniente España. He escaped, but his wife was killed. The attack sparked a war between the groups, and eventually, the fighting would cost Teniente España his life, but the Choneros would emerge intact.

“The Queseros ceased to exist, and the Choneros became renowned,” said the Choneros commander.

The Choneros’ new fame put them in the sights of the law. Teniente España’s successors were gunned down by the police one by one, opening the way for Rasquiña to take over as leader with Fito at his side.

But even though they had risen to the top of the organization, when there was killing to be done, Rasquiña and Fito would still do it themselves. And that would lead them to La Roca, after they were arrested and charged with murder in 2011.

At the time, La Roca housed Ecuador’s most dangerous and most powerful prisoners. There, Rasquiña was one of many killers, bank robbers, extortionists, kidnappers, drug pushers and traffickers.

Rasquiña was the last of the La Roca fugitives to be recaptured. Credit: Ecuador Ministry of Government

“When Rasquiña arrived, he didn’t have much power, he was just like everyone else,” said Alexandra Zumárraga, who oversaw La Roca after its opening in her role as Director of Social Rehabilitation in the Ministry of Justice. “They treated him badly.”

But he quickly imposed himself. Shortly after his arrival, Rasquiña got into a fight with a fellow prisoner who, according to witness testimony in his case file, had called him a snitch. A month later, that prisoner was dead. Witnesses in the case accused Rasquiña of contracting another inmate to shoot the prisoner dead.

The murder left its mark.

“Jose [sic] Luis Zambrano is a very dangerous subject, everyone knows it. He is the boss of the Choneros and with his money, he can do what he likes,” the cellmate of the victim told prosecutors as he pleaded to be put into witness protection.

Violence, though, was not Rasquiña’s main tool. He was smart and charismatic, and he knew how to use both.

“He had a lot of social intelligence, and he began to make allies, above all with the poor because those are the people who would really give him power and protection,” said Zumárraga.

He also began to forge alliances with the other criminals in La Roca.

“They transferred the most dangerous [criminals] there and I said to them, ‘You can’t have them here because those that were enemies are going to become friends,’” said Zumárraga. “And that is what happened, almost all of them became friends, and then they escaped.”

For Rasquiña, Fito, and the other Choneros, La Roca, which held drug traffickers with connections to international cartels and influential politicians, was a place to make more powerful friends and learn their trade.

“They were common criminals, but they went to prison with narcos and Mexican [drug traffickers],” said a military intelligence official, who spoke to InSight Crime on condition of anonymity.

La Roca was shut down shortly after the jailbreak, and when Rasquiña and Fito were recaptured they would enter a very different prison system, one that was rapidly changing. But La Roca had already laid the foundation for the next phase of the Choneros evolution.

The Renaissance

Around the time of the La Roca jailbreak, the Correa administration had begun construction on a series of “mega-prisons” in an attempt to combat overcrowding. Soon, over half of the prison population was housed in just four facilities. But the new prisons were poorly built and run, lacking guards, infrastructure, and basic services such as running water and adequate food. For the prisoners and prison officials, it was clear that Correa’s promises that rehabilitation programs would be at the heart of the system existed on paper alone. Corruption ran rampant.

“The famous prison management model was not like they sold it to us. It was a campaign thing, empty propaganda that was never institutionalized,” said a former government official who investigated the prison system for congress.

The government’s failures, though, created criminal opportunities. The provision of services became an extortion racket, where prisoners had to pay for the basics. The prisons were flooded with contraband and illegal businesses flourished, from restaurants to loan sharking. What’s more, by concentrating the population in the mega-prisons, the government took what had been a cottage industry of crime and corruption and ramped it up to an industrial scale.

“This business, which has always been there, started to get stronger,” said the former government official. “Before, it wasn’t this mega-criminal economy that you have now. With the mega prisons, everything was suddenly centralized.”

Controlling a single wing in the mega-prisons could mean an income of millions of dollars a year, and the profits on offer were potentially transformative for a group like the Choneros. But Rasquiña’s vision extended well beyond the prison walls.

“They realized that if they took control of the prisons, they would have an army,” said the intelligence official.

Rasquiña did not build that army from the ground. Instead, he recruited existing gangs in the prisons. He offered them access to drugs, guns, corrupt officials, and the sort of top criminal connections he had forged in La Roca. And he gave them some independence, the chance to run their crews and operations, as long as they answered to him.

“He was someone who was really permissive,” said a local leader from the Ñetas gang, who was imprisoned around this time. “He allowed [gangs] to be their own faction with their own names, as long as they worked for the Choneros.”

The strategy allowed him to create a federation of criminal groups within the prisons: He brought in bands of robbers, extortionists, and drug dealers. And he recruited from among the thousands of prisoners that were members of youth gangs like the Latin Kings, the Vatos Locos, and the Master of the Street. Above all, he targeted the Ñetas, an international gang born in the prisons of Puerto Rico.

“The youth organizations were used by these mafias and their leaders,” said the Ñetas leader. “They realized that we managed a lot of people, and they started using us as shock troops, an armed wing.”

These connections also gave Rasquiña a way to expand on the outside.

“They took control of the streets, the same way they took control of the prisons because most of the gang bosses with people on the streets are in prison,” said the Choneros commander. “They would arm the leadership, so they could order them to take charge of a neighborhood.”

Rasquiña had his army. Next, he would put it to use.

Tapping the Cocaine Boom

Rasquiña’s reformation of the Choneros created many of the organizations that would later be declared terrorist groups at war with the state: the Lobos, led by a bank robber who had been in La Roca with Rasquiña and Fito; the Tiguerones, formed by a prison guard who smuggled in contraband for Rasquiña; the Águilas, headed by a criminal who the Choneros commander said Rasquiña saved from an assassination plot; the Chone Killers, a Ñetas hit squad rebaptized in honor of their new paymasters; and the Fatales, Fito’s own faction within the Choneros.

But it was what Rasquiña did with his new federation that would position the Choneros at the center of the Ecuadorian underworld. He converted it into an army of criminal mercenaries, then placed that army at the service of the elites of organized crime – among them transnational drug traffickers.

At that time, Ecuador was emerging as one of the most important hubs in the global cocaine trade. And a new generation of Ecuadorian drug traffickers was emerging to capitalize on the boom.

The first major opportunity for the Choneros to stake their claim to this business came in their own backyard, Manabí. There, a fisherman named Washington Prado Álava, alias “Gerald” had built a drug trafficking empire, dispatching hundreds of tons of cocaine on boats to Mexico and Central America. And Fito leveraged his local connections to place himself at the heart of Gerald’s network.

“They were allies,” the Choneros commander said.

Fito organized trafficking logistics for Gerald, such as arranging the high seas refueling points for the drug boats, court documents show. And he escorted shipments, guarded stash points, and watched over safe houses packed with cash, anti-narcotics officials who participated in the investigation into Gerald told InSight Crime.

Fito was also in charge of violence.

“He gave Fito money to take care of him, to protect him,” the commander added.

The relationship gave Fito and the Choneros a foothold in the transnational trade as Gerald would pay them in drugs added to the loads, according to the Choneros commander. But Gerald’s trust in Fito was misplaced.

According to case files and the anti-narcotics investigators, Fito was allegedly behind a heist of a stash house holding $3 million of Gerald’s money. Gerald’s bloody search for the culprit would expose him to police, eventually leading to his arrest in Colombia. The antinarcotics officials said that with Gerald out of the way, Fito launched a campaign to wipe out what remained of his network, and he would later take over the Manabí corridor.

For the police, though, the Choneros were still just a blip on the radar.

Rasquiña Makes his Move

The police were not the only ones who were complacent about what was brewing in Ecuador’s prison system. By 2019, the new government of President Lenin Moreno had slashed the budget for the prisons, dissolved the ministry responsible for the penitentiary system and turned over operations to a newly created body that has since become a byword for incompetence and corruption – the Comprehensive Care Service for Adults Deprived of their Liberty and Adolescent Offenders (Servicio de Atención Integral a Personas Adultas Privadas de Libertad y Adolescentes Infractores – SNAI).

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) would later conclude that the reform represented a “true dismantling of the prison system.” And it left the prisons at the mercy of the Choneros.

The timing was crucial. Inside the prisons, rivals remained, in particular a coalition of Guayaquil gangs that would eventually coalesce under the banner of an organization called the Lagartos, or Lizards. Among their leaders was William Humberto Poveda Salazar, alias “El Cubano.”

“El Cubano was the most powerful, he had control of Guayaquil, not only inside the prisons but also outside,” said Zumárraga, who encountered El Cubano in La Roca, where he was known among officials as the “director killer” for ordering a hit on a prison director in 2007.

El Cubano’s power in Guayaquil gave him leverage in Ecuador’s most important cocaine dispatch point, the port city of Guayaquil. There, he and his allies offered security and hitman services to drug traffickers.

The Choneros’ assault against this alliance began in May 2019, when they stabbed to death a top rival leader in Latacunga prison in Cotopaxi. Weeks later, they murdered six members of another rival gang in the Litoral prison in Guayaquil.

Then they got their shot at El Cubano. For more than six months, El Cubano had been in a secure, holding cell, away from the general population. But in June, case files show, an order signed by two police colonels arrived instructing officials to transfer him to the maximum-security wing of La Regional, a Choneros stronghold. El Cubano’s sister would later tell prosecutors how El Cubano had called her when he was taken to his new cell. This looks wrong, he said. Get the lawyer, tell him to get me out of here, he pleaded.

But it was too late. Mere hours after their conversation, a group of more than a dozen prisoners took their guards hostage and forced them to open the door to El Cubano’s cellblock. After prying open his cell door with a crowbar, they stabbed him, burned his body, then kicked his decapitated head around the courtyard.

For many Ecuadorians, the moment became a grim milestone marking the point of no return in the country’s rapid descent.

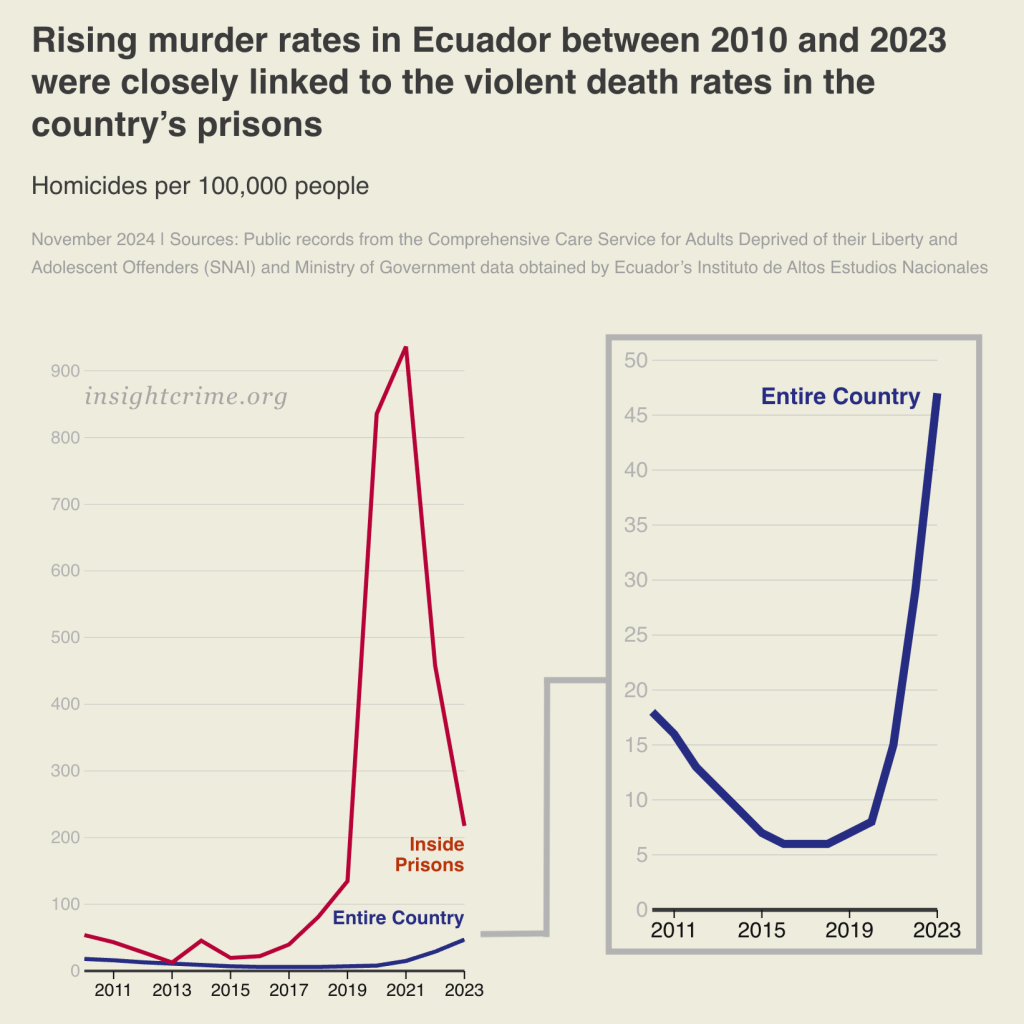

Murder rates inside and out of Ecuador’s prisons began to rise at the time of the Choneros expansion.

Murder rates inside and out of Ecuador’s prisons began to rise at the time of the Choneros expansion.

Almost a year later, in August 2020, the Choneros moved to finish the job when they launched an attack against the Lagartos in the Litoral prison that left 11 dead and forced the remaining Lagartos to lay down their weapons and negotiate their transfer to a secure facility.

Climbing the Underworld Pyramid

With their main enemies isolated and confined, the Choneros were at the height of their power, and Rasquiña began to partition the prison system into fiefdoms for the different factions of his federation.

“That was when they gave out the wings as a prize, every organization [within the Choneros] had its own wing,” the Ñetas leader told InSight Crime.

But Rasquiña’s ambitions were still not satiated.

Their next target, according to security and judicial officials, was Telmo Castro, a former army officer who had started escorting drug shipments through the country for the Sinaloa Cartel in the 2000s and became the most famous of the generation of Ecuadorian drug traffickers that emerged in the 2010s.

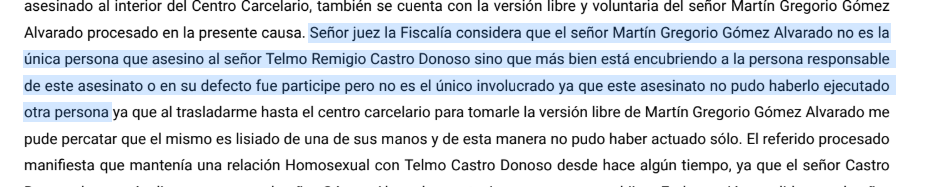

Castro was arrested in 2013, but like the Choneros, he had only grown stronger within the prisons. However, in December 2019, Castro was found dead in his prison cell – naked, bound by his hands and feet, and with 46 stab wounds. A fellow prisoner named Martín Gómez immediately confessed to the crime, providing authorities with an elaborate story of bondage sex play that spilled over into threats against his family.

However, investigators had trouble believing the confession, with the prosecutor telling the court he believed the prisoner either had not killed Castro or at least had not killed him alone, and he was covering for other people.

Excerpt of the case file in the murder of Telmo Castro

Excerpt of the case file in the murder of Telmo Castro

The prosecutor’s office never charged anyone else with the crime, but, according to the military intelligence official, a former police official and an organized crime prosecutor who spoke to InSight Crime, Rasquiña and the Choneros were likely behind the murder. A Choneros faction had provided Castro with his own security detail in prison, and it was those bodyguards who murdered Castro on the orders of Rasquiña, the intelligence officer said.

It is a theory strengthened by what would happen a year later, when three convicted cocaine traffickers that had worked with Castro – and were known as La Banda de los Mexicanos, or the Mexicans’ Gang, for their drug connections – were stabbed to death in Latacunga. One was Castro’s brother-in-law, according to court documents. Once again, the Choneros were reportedly responsible.

According to the intelligence official, behind the killings was Rasquiña’s ambition to move up in the drug world. As Fito had done with Gerald, Rasquiña was coming for the intermediaries between him and the transnational traffickers, he said. There were variations of these theories. The organized crime prosecutor, for example, claimed the Choneros took out Castro and his network because they had begun working with the Sinaloa Cartel’s rivals, the Jalisco Cartel New Generation (Cartel de Jalisco Nueva Generación — CJNG).

Whatever the exact motives, the results were the same: one of Ecuador’s most influential traffickers was removed from the chessboard, and the Choneros were rising through the ranks.

By that time, the Choneros had won another important, but ultimately, short-lived victory: Rasquiña was a free man.

The Danger of Freedom

Rasquiña’s leadership had been central to the Choneros’ rise. But the federation’s dependence on him would lead to their decline. Because while the Choneros’ network was based on cold, hard, criminal logic, it was held together by a cult of personality.

“They all saw him as a leader, and they saw him as someone intellectual,” said a former prison director, who did not want to be identified for security reasons. “They idolized him.”

That veneration was on full display in June 2020, when Rasquiña strode out of Latacunga prison flanked by a guard of honor, rows of prisoners applauding and shouting their support.

He had been granted parole after a legal process riddled with suspicions and controversies, and which would later land one judge in prison and put another under investigation. The powerful but controversial former minister of the interior, Jose Serrano, who has himself faced accusations of ties to organized crime, went public with allegations the government had made a deal with Rasquiña, allegedly swapping his freedom for a pledge to maintain order in the prisons – allegations the government denied.

But it made no difference. Rasquiña was free. It was a moment that appeared to seal his ascent to the upper levels of Ecuadorian organized crime, the levels of not only power and wealth, but also of impunity.

Instead, it sealed his downfall. On December 28, 2020, while Rasquiña sat at a café in a Manta mall, a man in a white vest and baseball cap bounded over to him, raised a gun, and fired at point-blank range.

Rasquiña was dead, and although it was hard to see it at that moment, Ecuador had begun its fall into the criminal abyss.

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus