Allah giveth, and Allah taketh: what remains of Hezbollah after Israeli strikes

Over the past month, Israel has launched several unprecedentedly powerful strikes against the Lebanese terror group Hezbollah.

Its long-time leader, Hassan Nasrallah, was killed in one of them, and several of his potential successors, including the proposed new leader of Hezbollah, Hashem Safieddine, were similarly eliminated in quick succession.

The explosions of pagers disabled Hezbollah’s lower-level command and disrupted its primary alert system, while heavy missile barrages destroyed its weapons stockpiles. It is evident that the organization will no longer be as influential or dangerous as it once was: there is no one with sufficient authority to step in as the clear successor to Nasrallah, and the arms the group has accumulated over the years seem likely to be eradicated by the Israeli military within a matter of weeks. However, it is still too early to count Hezbollah out entirely — its fate will ultimately be decided by Iran.

Exporting the revolution

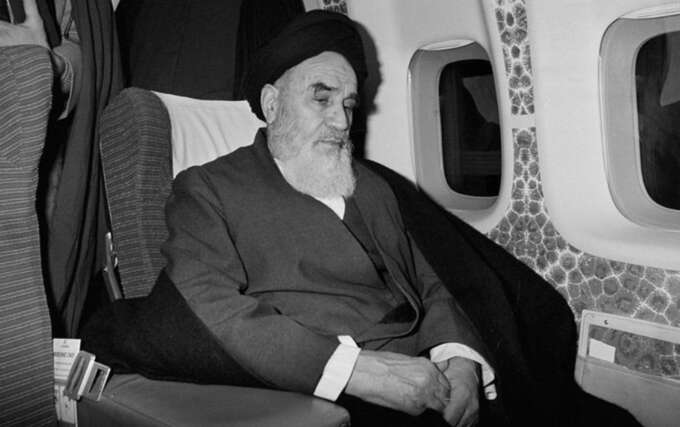

“We must do everything in our power to export our revolution around the world!” — declared Ayatollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader of the newly established Islamic Republic of Iran back in the 1980s. He and his allies saw it as self-evident that the victorious Islamic Revolution in Iran should spread, at the very least, throughout the Middle East and, ideally, become a global movement. However, several key factors stood in the way of these ambitions, the most significant of which was religious. Iran is a Shiite country, whereas in the Arab states, either the population is overwhelmingly Sunni, or, as in the case of Bahrain or Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, Sunnis had seized full control and governed over a Shiite majority. Under these circumstances, Iran found it easiest to establish a foothold in Lebanon.

Ayatollah Khomeini

Lebanon is a country unlike any other in the world. Isolated from its neighbors by forests and mountains, its territory has served for centuries as a refuge for religious groups and sects considered heretical — or outright hostile — by the Islamic authorities. Christians (Catholics, Orthodox, and followers of the Armenian Apostolic Church), Shiites, Druze, Alawites, and Sunnis all found a home here.

The territories of what is now Lebanon have served for centuries as a refuge for religious groups and sects considered heretical and hostile by the Islamic authorities

For centuries, these communities lived under the (often nominal) rule of Arab caliphs, Ottoman sultans, and, after World War I, the French. The latter devised Lebanon’s intricate political system in the 1940s as they were withdrawing from the Middle East. This system, known as confessionalism, allocated a fixed number of seats in the national parliament to each religious community and ensured that key governmental positions were distributed among the largest groups. According to the constitution, only a Maronite Christian can be president, the prime minister must always be a Sunni, and the speaker of parliament is elected exclusively from among the Shia. This approach was meant to provide every community with a role in governing the country. However, things did not go as planned.

At the time of Lebanon’s independence in 1943, Christians made up the majority of the population. But soon, Muslims, with their traditionally larger families, began to catch up numerically. The demographic balance was further impacted by the influx of thousands of Palestinian refugees — predominantly Sunnis — who were driven into the country by the Arab-Israeli wars. Muslims began demanding a greater say in Lebanon’s internal affairs and sought to revise the parliamentary quotas, while Christians resisted such pressure as best they could. In 1975, sectarian tensions escalated into a civil war. At the start of the conflict, the largest Shia group was the Amal Movement, which emerged shortly before the outbreak of hostilities, declaring its aim to protect Shia from potential threats emanating from Sunnis and Christians. Amal’s main adversaries soon became the Sunni refugees associated with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

At the time of Lebanon’s independence in 1943, Christians made up the majority of the population

In the early 1980s, a new front against the Palestinians was opened via Israel’s invasion of southern Lebanon. Although there were neither formal relations nor even a temporary alliance between Amal and the Israelis, the intervention led to a serious crisis within the Shia community in Lebanon. Amal leaders advocated for negotiations with the Israelis and the preservation of a secular state model, with some redistribution of parliamentary and governmental seats in favor of Muslims.

The birth of Hezbollah

Meanwhile, ideas of a global Islamic revolution began to spread among Lebanese Shia militants — and not without the involvement of agents sent by Tehran. Supporters of these ideas demanded the establishment of an Islamic Republic in Lebanon and rejected any compromises with Israel. They believed that the Jewish state should be destroyed and that all Sunni Palestinians from Lebanon, possibly along with any other Lebanese who did not wish to live in a pro-Iranian republic, should relocate. These Shia radicals broke away from Amal and formed their own militant organization. Funding, weapons, and instructors were brought in from Iran. In this way, the ayatollahs fulfilled the mandate of their own constitution, which calls for the creation of conditions for the spread of the Islamic revolution worldwide. Thus, Hezbollah was born.

Shia radicals broke away from Amal and formed their own militant organization. Thus, Hezbollah was born

Without Iran, Hezbollah would not exist — at least not in its current form. Throughout its history, the organization has been ideologically, politically, and financially linked to Tehran. However, the question of whether Hezbollah was originally an Iranian project or if the ayatollahs merely took control of an organization ideologically close to them remains open. What is undeniable is that Hezbollah has become one of the most dangerous terrorist organizations in the world.

“Beirut has become synonymous with death and destruction,” stated an editorial in the Pittsburgh Post, published in April 1983, shortly after a large-scale terrorist attack in the Lebanese capital. In that particular instance, a suicide bomber had detonated a van packed with nearly a ton of explosives outside the U.S. Embassy, killing over 60 people. A few months later, in October 1983, 307 people lost their lives when explosives-laden trucks were detonated at the gates of barracks housing American and French troops. Both attacks were carried out by Hezbollah, which in 1983 was still so inconspicuous that its involvement in some of the bloodiest attacks in history became known only years later.

A column of smoke over the U.S. Marine Corps Headquarters in Beirut, October 23, 1983

Hezbollah officially announced itself in 1985 when it released a political manifesto calling for the expulsion of all Western armies from Lebanon (such troops were only in the country in the first place because of the civil war). The manifesto expressed loyalty to the Supreme Leader of Iran and promised to destroy Israel. At that time, Hezbollah was just one of many armies fighting in Lebanon, but it would soon become one of the main political forces in the country under the leadership of Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah.

Born a Sheikh

“When I was 10 or 11 years old, my grandmother had a scarf. A long black scarf. I would wrap it around my head and tell my family, ’I am a theologian; you must pray behind me,’” recalled Hassan Nasrallah, who has never appeared in adulthood without a black turban on his head.

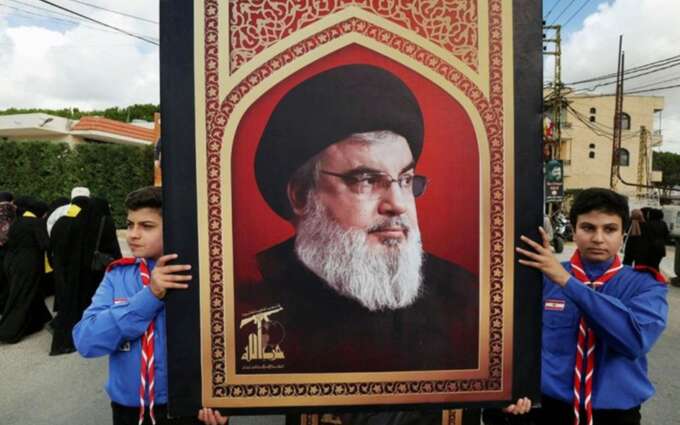

Hassan Nasrallah

This type of turban is not just a distinguishing feature of a theologian — its color in Shia Islam signifies that the wearer is a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad. In reality, there are tens or even hundreds of thousands of descendants of the Prophet in the world (there has even been speculation that British monarchs belong to this lineage), but Hassan Nasrallah has become the most famous among them. At first glance, there was nothing to suggest this: his parents were not religious, they operated a small business, and they sent Hassan, like his many brothers and sisters, to a secular school. Hassan pursued religious education on his own and even organized a Quran study group.

When the war broke out in Lebanon, the future sheikh was only 15 years old, but he was already influential enough to be appointed as the official representative of Amal in the village where his family lived. After finishing high school, Nasrallah went to Iraq to study theology, but he was soon expelled (along with other Lebanese Shiites) by Hussein’s government. The young Shiite returned home fully indoctrinated with the ideas of the Islamic Revolution and was even included in a small circle of Shiite intellectuals, through whose efforts Hezbollah split from Amal.

Since the establishment of the organization’s political wing in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Nasrallah has been one of its leaders and ideologists. In 1992, he was elected Secretary General of Hezbollah, and in the first post-war elections, the new party secured eight seats in the Lebanese parliament. The structure of the organization’s political wing was formed then and remains unchanged to this day. Hezbollah is led by its Secretary General, who oversees the organization’s Supreme Council (Shura), which also includes the Deputy Secretary General and the heads of five other councils. Among them are the Political Council, responsible for cooperation with other parties and organizations; the Parliamentary Council, which regulates Hezbollah’s legislative activities; the Executive Council, whose members manage economic and charitable activities; the Legal Council; and the Jihad Council, which is in charge of planning military operations. The Secretary General has the authority to intervene in the work of any of these councils, and no decisions made by them can be implemented without the approval of the head of the organization.

In 1992, Nasrallah was elected Secretary General of Hezbollah, and the party secured eight seats in the Lebanese parliament

Formally, the Executive Council has the authority to appoint a new Secretary General, selecting one from among its members. However, since the organization’s founding, the Secretary General has only changed through elections once. In the early 1990s, the first leader of Hezbollah, Subhi al-Tufayli, relinquished his position to Abbas al-Musawi, who was killed a few months later by Israeli airstrikes. Since then, until October 2024, Hassan Nasrallah had led Hezbollah. When he first took the helm of the organization, there was still a provision limiting the highest office to two terms. To accommodate him, the Shura removed this rule, allowing Nasrallah to be re-elected an unlimited number of times.

Many Lebanese are outraged by this, but it is Hassan Nasrallah who became the true face of the country, Lebanon’s most recognized citizen in the world. His portraits hang on the streets of Beirut and Tehran, buttons bearing his likeness were sold in souvenir shops in Gaza, and magnets featuring Nasrallah were popular items in Damascus. Under his leadership, Hezbollah transformed from an obscure group into Iran’s main and most capable ally.

Hassan Nasrallah became the true face of the country, the most recognized citizen of Lebanon in the world

The Shura’s decision not to replace Nasrallah with someone else could not have been made without Tehran’s approval. The ayatollahs needed a loyal yet active and pragmatic leader capable of making independent decisions that would not contradict the interests of the Islamic Republic. Hassan Nasrallah proved to be just such a person, which is why he remained the unchanging Secretary General of Hezbollah. He transformed Hezbollah from a band of thugs into a vast empire with a nearly all-powerful political wing, an influential media structure, and a network of charitable foundations that used basic necessities like grains and canned goods to effectively buy the loyalty of impoverished Shiites. Furthermore, the Secretary General managed not only to preserve the organization’s core — the old band of thugs — but also to evolve it into a modern, capable terrorist army.

Vote and fight

For decades, Hezbollah combined political activity with terrorism, and it was often unclear where one ended and the other began. Until 2008, inter-party agreements ensured the organization two ministerial portfolios in any government. In 2008, the party and its allies secured even more significant concessions from other political forces. Hezbollah was guaranteed one-third of all ministries (regardless of increases or decreases in the number of ministries, this proportion remained constant) plus an additional one. In effect, Hezbollah gained not just a third of the portfolios, but complete control over the government. Any attempt by other ministers to act against the wishes of Nasrallah and his close aides would lead to a boycott of cabinet work by Hezbollah ministers and provoke a severe political crisis.

Control over the Lebanese government was essential for Hezbollah. Its armed wing remained the only non-state military formation that had not been disbanded after the civil war. The presence of a well-armed and trained military group among the Shiites unsettled other communities in Lebanon and raised concerns among global players. UN Security Council Resolution 1709, adopted in August 2006, included a call for the disarmament of the organization. To prevent its opponents in Lebanon from interpreting this call as a mandate for action, Hezbollah secured (by intimidating or bribing representatives of other political forces) a de facto right of veto in the government. This situation persisted until 2019, when mass protests by Lebanese citizens driven to despair by an endless financial crisis forced the authorities to reconsider the cabinet’s configuration and compelled Nasrallah to make concessions.

Alongside political intrigue, the blackmailing of competitors, and political assassinations, Hezbollah armed itself, fought, and prepared for new wars. The group takes credit for the withdrawal of Israeli troops from southern Lebanon in 2000, although internal Israeli factors influenced the decision to end the occupation as much as Hezbollah’s ongoing attacks did. In 2006, Hezbollah dragged Israel into a short but bloody conflict in Lebanon, marking the first war for the Jewish state not against Arab countries or Palestinian groups, but directly against Iranian proxies. Nasrallah’s fighters and military advisors also intervened in the Syrian civil war, contributing to the survival of Bashar al-Assad’s regime.

No leader, no weapons: what’s next?

In the 2020s, Hezbollah entered a new phase, having lost some political positions but remaining one of the key power players in the Middle East. It still controlled vast territories in southern Lebanon along the border with Israel. Hezbollah transformed these areas into a massive military base, concentrating its impressive stockpiles of rockets and artillery (up to 150,000 units), digging bunkers and shelters for its fighters, and setting up workshops for building and maintaining drones.

For years, the group’s specialists have been working on a communication system designed to be as opaque as possible to their enemy — namely, Israel. Initially, Hezbollah laid down separate telephone lines throughout Lebanon that were separate from the national network, but they soon discovered that someone had tapped into these lines. Consequently, they abandoned wired phones in favor of a paging system. This system was built from the ground up — by Hezbollah and for Hezbollah. It was intended to be inaccessible to any external forces.

Hassan Nasrallah personally urged his followers to abandon mobile phones and rely solely on pagers. Pagers became the primary tool for mobilizing grassroots commanders within the group. Upon receiving encrypted messages signaling the start of mobilization, these commanders were expected to gather their subordinates and send them to the designated locations indicated by the leadership. In theory, Hezbollah had the capability to assemble its entire army within hours and direct it to the bunkers and shelters in the south for an attack on Israel.

Hezbollah had the capability to not only assemble its entire army within hours but also direct it to the bunkers and shelters in the south for an attack on Israel

Until recently, the organization was supported by three pillars: its border military infrastructure, a theoretically inaccessible mobilization system for fighters through pagers, and, of course, Hassan Nasrallah himself. Then all three of these pillars collapsed within a matter of days. First, Hezbollah commanders experienced an explosive surprise when their pagers simultaneously detonated, resulting in the loss of dozens, if not hundreds, of military specialists and leaving the group without its main tool for notification and mobilization. Next came a massive Israeli attack on the group’s border arsenals and caches. Finally, Hassan Nasrallah himself was killed by an Israeli missile strike on one of his bunkers.

It is clear that the organization will no longer be as influential and dangerous as it has been in recent years. In the shadow of Nasrallah, who never showed a willingness to share power, no leader has emerged who can match his popularity and influence. And the weapons that have been accumulated over the years are likely to be destroyed by Israel in the coming months or even weeks.

However, it is premature to write off Hezbollah. The overwhelming majority of Lebanese Shiites traditionally vote for the group, or, at the very least, regard it with respect. Societal levels of support for Hezbollah have proven remarkably resilient, even during serious economic and political crises. Furthermore, while the group’s military structure has suffered, it has still endured. The rank-and-file fighters — including a number of poorly trained militias — may total up to 100,000 and were largely unaffected by the pager explosions.

The group’s current circumstances even bears some resemblance to its early years, which were characterized by relatively unknown leaders who did not remain in power for long, a shortage of mid- and lower-level commanders, and administrative disarray — all occurring during an active phase of war. Looking ahead, the future of Hezbollah largely hinges on Iran. It may seek to replenish the group with funding and weapons, doing its best to restore its arsenals and influence. And yet, given the current confluence of forces in the Middle East, Iran might instead shift its focus towards closer collaboration with the Yemeni Houthis or various Iraqi militias. Beneath the black turbans of Iranian ayatollahs, the fate of their once-favored allies is being determined.

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus