Report shows Russia’s war with Ukraine is accelerating the global climate emergency

The most comprehensive analysis ever of conflict-driven climate impacts reveals emissions greater than those produced by 175 countries in a year.

The climate cost of the first two years of Russia’s war on Ukraine was greater than the annual greenhouse gas emissions generated individually by 175 countries, exacerbating the global climate emergency in addition to the mounting death toll and widespread destruction, research reveals.

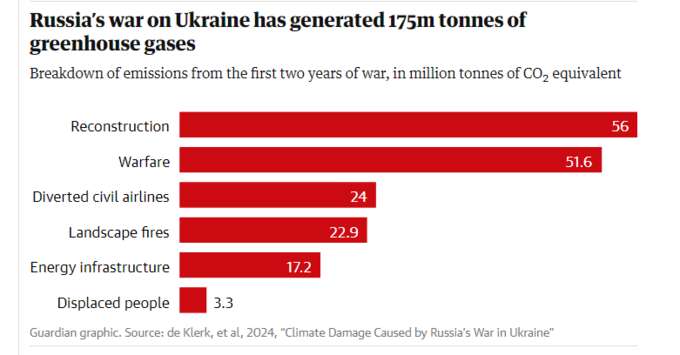

Russia’s invasion has generated at least 175m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e), amid a surge in emissions from direct warfare, landscape fires, rerouted flights, forced migration and leaks caused by military attacks on fossil fuel infrastructure – as well as the future carbon cost of reconstruction, according to the most comprehensive analysis ever of conflict-driven climate impacts.

The 175m tonnes includes carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and sulphur hexafluoride (SF6), the most potent of all greenhouse gases. This is on a par with running 90m petrol cars for an entire year – and more than the total emissions generated individually by countries including the Netherlands, Venezuela and Kuwait in 2022.

Historically, governments have accounted poorly for the climate cost of war – and of the military industrial complex more broadly. Official data is extremely patchy or nonexistent due to military secrecy, and there is limited frontline access for researchers. The economic cost of the greenhouse gases, which will have global consequences, is even less well understood.

But according to the new report by the Initiative on Greenhouse Gas Accounting of War (IGGAW) – a research collective partly funded by the German and Swedish governments, and the European Climate Foundation – the Russian Federation faces a $32bn (£25bn) climate reparations bill from its first 24 months of war.

The UN general assembly has said that Russia should compensate Ukraine for the war, leading the Council of Europe to establish a registry of damage, which will include climate emissions. Frozen Russian assets could be used to settle the costs. The reparations estimate draws on a recent peer-reviewed study that calculated the social cost of carbon as $185 for every ton of greenhouse gas emissions.

The IGGAW lead author, Lennard de Klerk, said: “Russia is harming Ukraine but also our climate. This ‘conflict carbon’ is sizeable and will be felt globally. The Russian Federation should be made to pay for this, a debt it owes Ukraine and countries in the global south that will suffer most from climate damage.”

The report is the most comprehensive analysis of the climate cost of any conflict – and the first time reparations have been calculated for war-related climate impacts.

The report found:

-

A third of the warfare emissions come directly from military activity, with fuel used by Russian troops accounting for 35m tCO2e – the single greatest source of greenhouse gases. Other sources include the manufacturing of carbon-intensive explosives, ammunition and defence walls along the frontlines by both countries, as well as the fuel used by allies to deliver military equipment.

-

Another third is attributed to the vast quantities of steel and concrete that will be needed to reconstruct the damaged and destroyed schools, homes, bridges, factories and water plants. Some reconstruction has already taken place and in some cases the replaced structures have been destroyed again. The scale of the carbon impact will, in the long term, depend on whether traditional, carbon-intensive or modern, more sustainable techniques and materials are used to rebuild, according to Neta Crawford, the author of The Pentagon, Climate Change and War.

-

The final third was generated by fires, rerouting of commercial planes, strikes on energy infrastructure and, to a lesser extent, the displacement of nearly 7 million Ukrainian people and Russians.

Landscape fires have increased in size and intensity on both sides of the border since the invasion. In the first analysis of its kind, 1m hectares (2.47m acres) of scorched fields and forests were linked to military causes, accounting for 13% of the total carbon cost. Most fires took place close to the frontlines, but small blazes got out of control countrywide due to the redeployment of foresters, fire crews and equipment. Almost 40% of Ukraine’s 4,216 fire trucks have been damaged.

Russia deliberately targeted energy infrastructure, especially during the first months of the war, generating major leaks of potent greenhouse gases. The methane that escaped into the sea after the destruction of the Nord Stream 2 pipelines generated about 14m tCO2e. Another 40 tonnes of SF6 (equivalent to about 1m tonnes of CO2), is thought to have leaked into the atmosphere due to Russian strikes on Ukraine’s high-voltage network facilities. SF6 is used to insulate electrical switchgear and has nearly 23,000 times more heating potential than carbon dioxide.

Aviation fuel consumption has rocketed as European and American commercial airlines are banned from Russian airspace, while Australian and some Asian carriers have been taking circuitous routes as a precaution. The extra miles have generated at least 24m tCO2.

The forced movement of people – escaping the impact of war or conscription – has generated almost 3.3m tCO2e, the analysis found. This includes the transport-related emissions by more than 5 million Ukrainians seeking refuge in Europe as well as millions of internally displaced people and Russians fleeing Russia.

“The analysis is the most up-to-date and thorough snapshot we have of the climate consequences of Russia’s invasion, helping to lift the fog of war that exists also when it comes to the environmental costs of conflict,” said Ruslan Strilets, the minister of environmental protection and natural resources of Ukraine. “It will be an essential plank in the reparations case we are building against Russia.”

Overall, the climate consequences of war and occupation are poorly understood. Thanks in large part to pressure from the US, reporting military emissions is voluntary, and only four countries submit some incomplete data to the UN framework convention on climate change (UNFCCC), which organises the annual climate talks.

One recent study found that militaries account for almost 5.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions annually – more than the aviation and shipping industries combined. This makes the global military carbon footprint – even without factoring in conflict-related emission surges – larger than that of all countries except the US, China and India.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has triggered a surge in military spending, particularly in Europe, boosting demand for explosives, steel and other carbon-intensive materials that will inevitably lead to more military emissions – which will not be accounted for by countries or international climate action plans.

“The new monetary estimate of climate damage highlights the important role of greenhouse gas emissions accounting for conflicts,” said Linsey Cottrell, an environmental policy officer at the Conflict and Environment Observatory. “We critically need international agreement on how conflict and military emissions are measured and addressed.”

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus