Fito’s fortress: Ecuador prison becomes criminal hub

In the early hours of the morning of January 7, 2024, a police and military task force stormed La Regional, one of two major prisons in Guayaquil.

They had come for Ecuador’s most infamous criminal: José Adolfo Macías Villamar, better known as “Fito,” the leader of the Choneros, the country’s most powerful prison gang. The authorities were planning to transfer him to a more secure facility. But when they reached his cell, it was empty, reported by insightcrime.

Fito had escaped from a maximum-security facility for the second time in ten years. But unlike 2013, when he and 17 more of Ecuador’s most dangerous criminals staged a cinematic jailbreak, this time he left no trace: no handcuffed guards or cut fences; no footprints or boats lying in wait. He had simply vanished.

Quickly, different versions circulated about what had happened. The president’s press officer appeared on television to say Fito had escaped just hours before the security forces arrived after someone tipped him off about the plan to transfer him from La Regional – and, according to media reports, back to La Roca, the high-security prison he had escaped from a decade earlier. But a former minister took to the radio and claimed Fito had escaped weeks before by switching in a double during a medical visit.

Within days, two prison guards were charged in connection with the escape, and La Regional’s prison director later went on the run with her family. But nearly a year later, there is still no official version of how Fito escaped.

“It’s an enigma,” a local Choneros commander, who had previously received his orders directly from Fito, told InSight Crime. “No one knows. We don’t even know. Some say he left through the big gate, that they opened the door and out he went. But others say they did other things to get him out.”

While the logistics of Fito’s escape are an enigma, there is no real mystery to how it could happen: Fito escaped La Regional because he ran La Regional. Over the previous five years, the weakness and corruption of the state had allowed Fito to convert La Regional into his personal fiefdom. But more than that, he had turned it into a command center, from where he managed an illicit empire worth tens, if not hundreds of millions of dollars, and directed a vicious criminal conflict that plunged Ecuador into bloodshed and chaos.

The King is Dead

The mafia war waged by Fito from La Regional began with shots fired in a shopping mall in the city of Manta, where Fito’s predecessor Jorge Luis Zambrano, better known as “Rasquiña,” or “JL,” was killed in December 2020.

Rasquiña was the mastermind of the Choneros’ evolution into Ecuador’s most influential criminal network and the creation of the prison gangs that would become known in Ecuador as “the mafias.” With Fito at his side, he had united youth gangs, bank robbers, extortionists, and microtraffickers into a powerful criminal federation that controlled prisons, trafficking corridors, and poor neighborhoods around the country and acted as mercenaries at the service of organized crime elites.

Rasquiña was an unusually powerful gang boss. Using a combination of charisma, guile, and violence, he’d forged an unprecedented network while reaching almost saint-like status in the Ecuadorian underworld.

“When he died, all the gangs asked me permission to hold a minute of mourning for him, and they spent all day in mourning, everyone dressed in black,” a former prison director, who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons, told InSight Crime. “People were crying, people who had never even seen Rasquiña.”

Who killed Rasquiña remains a mystery. The criminals, police, military, and intelligence agents all have their theories. Most of them boil down to one thing: ambition. Where they differ is on whose ambition: Rasquiña’s, the drug traffickers he worked with, or the gang bosses who worked for him.

Many of those theories center on the massacre of a gang of drug traffickers in the Latacunga prison some weeks before Rasquiña’s murder, and the murder of the Ecuadorian kingpin that gang had worked for, Telmo Castro. According to a military intelligence official, who spoke to InSight Crime on condition of anonymity, Rasquiña had ordered the killings to move up in the world of transnational cocaine trafficking. But his ambition had spooked the other traffickers, who feared they would be next, the official said.

“JL had become a danger [to them],” he said, using Rasquiña’s other nickname.

Others said the battle centered around who was working with the Sinaloa Cartel and who was moving towards the Jalisco Cartel New Generation (Cartel de Jalisco Nueva Generación – CJNG). The rivalry between the two most powerful Mexican criminal federations had spread to Ecuador in the years prior, but the details were fuzzy and sometimes contradictory. One organized crime prosecutor told InSight Crime the Choneros had moved against Castro and his network because they had been seeking to strike deals with the CJNG, but an anti-narcotics investigator said another trafficker working with the CJNG then targeted Rasquiña to upset the balance of power.

“There is another leader that we have strong evidence is working with the Jalisco Cartel New Generation,” he said. “We think he was behind JL’s murder. He did it so the Choneros would be weakened and divided.”

One thing was clear: It was within the Choneros federation where the killing itself was most likely planned and executed, underworld sources and officials told InSight Crime. That federation was a patchwork of violent prison and street gangs, which quickly began to point fingers at one another. After the murder, Fito blamed the Lobos, one of the most powerful factions within the Choneros, according to the Choneros commander. And the Lobos blamed Fito.

It almost did not matter what the truth was because the result was the same: The Lobos formed a new alliance of former Choneros factions, which was backed by Ecuadorian drug traffickers and moved drugs for the CJNG. The Choneros’ federation was done, and Ecuador was about to explode into violence.

“Rasquiña was betrayed by his own trusted people,” said the Choneros commander. “They killed him and that started the division into different groups. And then the war began.”

Drawing the Battle Lines in Blood

The vacuum left by Rasquina’s death would prove impossible to fill. According to testimony later given in a congressional hearing on prison violence, in early 2021, police intelligence units issued 19 alerts about the prospect of violence in the prisons following Rasquiña’s murder.

Among them was one issued on February 22, 2021, when police said that they had detained a prison guard trying to smuggle two guns into La Regional that were to be used to kill the leaders of the Choneros. The weapons, according to the Choneros commander, were destined for a gang member who had been promised control of his own prison wing and the criminal economies within if he killed Fito.

The hit failed. And Fito was quick to retaliate. The call came in the middle of the night, a former prisoner in La Regional who witnessed the massacre told InSight Crime. The Choneros member in their cell had the habit of putting his calls on speakerphone – to make them all complicit in criminal activity, he believed. So the witness could hear the order on the other end of the line that, at a certain hour, they should leave their cells and attack their rivals.

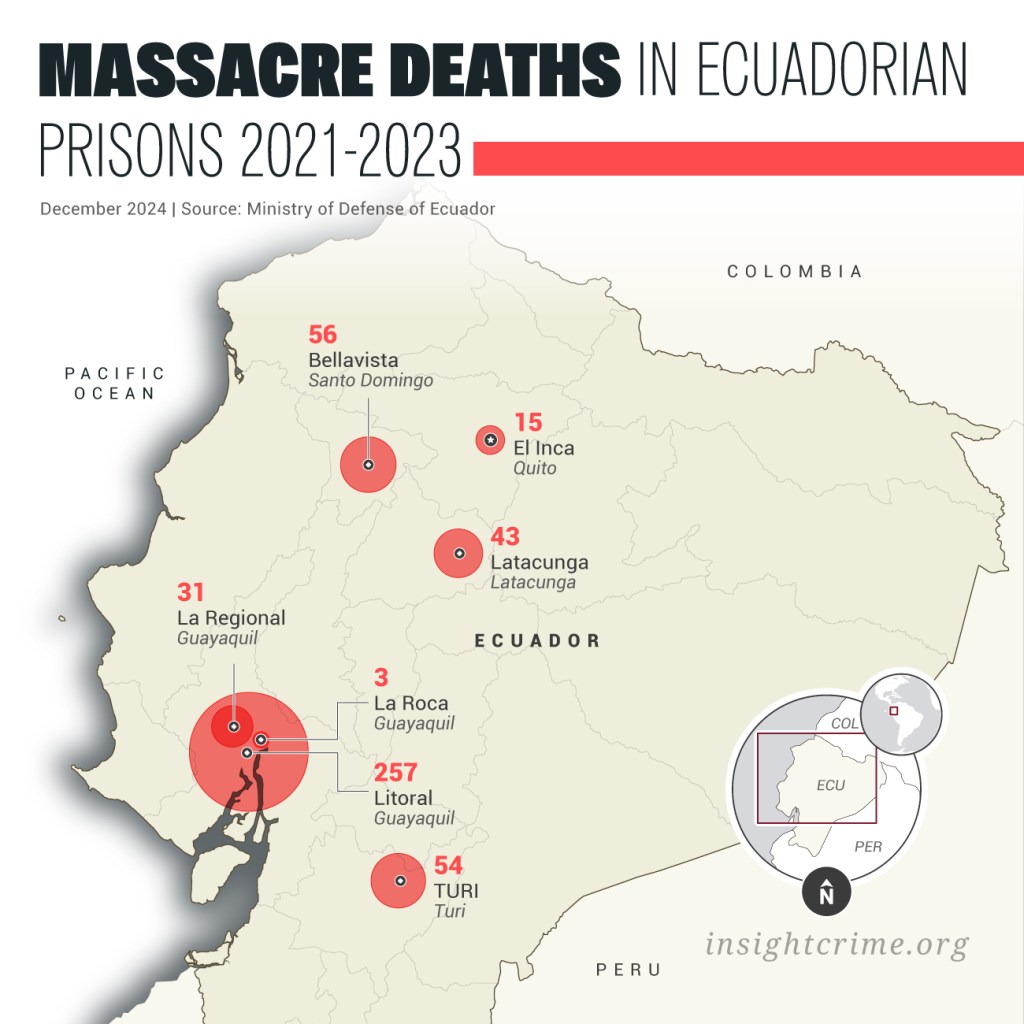

The Choneros were armed with two pistols and shanks, the prisoner said. They killed 31 people, according to official figures.

“They went out there in a frenzy, I have never seen anyone high on blood before, but they were high on blood, on killing,” he said. “It was a terrible thing to see, a person totally stained with human blood from the head down.”

The rest of the inmates shut themselves in their cellblocks and waited for the authorities to intervene. It took days.

“[We were left] without guards, without doors, without food,” the witness told InSight Crime. “Those of us left were those who had nothing to do with it because we didn’t know what we could even do, where we could go.”

The killing in La Regional lit the fuse for the mafia wars. Orders flew from gang leaders to their soldiers in prisons across the country: attack.

In total, 79 people were killed in four different prisons, according to the official figures. But it wasn’t just how many died. It was how they died. Videos and photos of the killing sprees seeped out – prisoners hacking off heads with stubby knives, holding human hearts in their hands, and pumping bullets into twitching corpses. The message was clear: There were no more limits on violence.

Ecuador would never be the same again.

Divide and Get Conquered

Following the slaughter, the authorities faced a dilemma that prisons around the world do: leave prison gangs mixed in the general population and risk more violence, or separate them by gang affiliation, which helps them recruit, retool, and organize. Ecuador chose to pull out whatever surviving minority gang members were left in the different wings and prisons and placed them with their own gangs.

“I had to separate them, and at the national level as well, they had to be separated, which was never the idea. It is not the appropriate thing to do in a normal situation because the idea is not to have one gang that is the owner of a prison,” said the ex-prison director.

Each prison and wing was now controlled by a single mafia, offering them a lucrative source of income, and a safe haven. The mafia takeover of the prison system was complete.

The Choneros, which were still Ecuador’s largest prison gang, seized La Regional and Rodeo. Their main rivals, the former Choneros faction known as the Lobos, took Latacunga and Turi. Smaller prisons and control over the wings of Ecuador’s biggest prison, Litoral, were divided up between the Lobos and the Choneros, as well as the Lobos’ junior partners in the breakaway coalition of rebel Choneros, like the Tiguerones and the Chone Killers.

“The government gave them a structure, and it gave them security, they were much safer inside than out,” said the intelligence official.

Inside La Regional, Choneros commanders ran every sector and every wing. At the head of it all was Fito. A decade after his original arrest, Fito was by then a stocky, middle-aged man with an unkempt beard that swirled its way down to his chest. But he retained a powerful criminal aura.

“He was educated, polite, and very methodical,” said a former senior official in La Regional, who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons. “He thinks a lot before he speaks, and he is calm, you would see him as a normal person, but behind that passivity, he could say at any moment, ‘Bitch, kill those 50 people,’ or, ‘Kill 100.’”

Control of La Regional also meant control of multimillion-dollar prison rackets. It came with a price tag. Fito and the Choneros had to pay off the guards, police, and officials from the profits they earned. Still, benefits followed – if the mid-level prison authorities sought to intervene to curb the Choneros’ freedoms or limit their power, they came up against superiors who refused to act or even reversed their orders, the official said.

“On one occasion I met with a minster and a police commander, and I told them they had to come here to right the ship,” he said. “[Their response] was like saying, ‘Let’s not kick that hornets’ nest.’”

Housed in the maximum security wing of La Regional, Fito and his top two lieutenants had their own cell blocks. The wing had everything from televisions and air conditioning to ice cream makers and a bakery. Thanks to medical certificates attesting to the inmates’ dietary needs, special meals were brought for them every day – steak, lobster, fish, and ceviche, according to the official. And when the pandemic hit, they smuggled in Covid vaccinations, the official added.

The Choneros also converted La Regional’s protective custody wing into a nightclub. The club had a well-stocked wooden bar, a sound system, and a rubber-bottomed swimming pool, the former prisoner said. When the pool was filled ahead of a party, the entire wing went without water, he added.

The parties would get rowdy. Sex workers were often smuggled into the prison, and violence could break out. For those prisoners not invited, the parties could be terrifying events.

“When they drank, they would get difficult,” said the prisoner, who by this point was housed in protective custody. “Everyone would lock themselves in because it would scare them.”

But the fear went far beyond drunken violence, it was how the Choneros maintained control of La Regional.

“That is the power that gives you strength, the fear that you can impose,” said the official. “The knowledge that you can order someone to kill.”

But ruling by fear comes with its own price, and with time, Fito became more paranoid. Every night, the official said, Fito’s bodyguards would lock the other inmates in his cellblock into their cells with keys he kept himself. The prisoners would stay in their cells until he was awake. According to the prison official, wherever Fito went, he was flanked by armed bodyguards, including when he met with the authorities.

“I would say to him, ‘What can I do to you? Why are you going around with all these people like that?’” the official explained. “He said, ‘I’m not scared of you. You’re not going to do anything. But not everyone in here loves me.’”

The War Outside

Throughout Fito’s reign, there were no more massacres in La Regional, and it was one of the most peaceful prisons in Ecuador. But that was because Fito was using it as a respite, a place from where he could direct his forces in the other prisons and try to rebuild the federation that Rasquiña once commanded.

“[La Regional] is one of the calmest prisons there has been. There was nothing going on there,” said the former prison director. “But what was happening? It was from there they were giving the orders.”

The fractious breakup of the Rasquiña-led federation had created the conditions for a messy and complex struggle. The Choneros’ efforts to repel the advances of the Lobos and their coalition partners led to a conflict characterized by shifting alliances, betrayals, and fragmentation, as well as by extreme violence. And while it played out simultaneously on the inside and outside, its contours can be traced through the mass killings taking place in the prison system.

Over the rest of 2021, for instance, at least 214 people were killed in four further massacres. All but one of them was in Ecuador’s biggest prison, Litoral. There, the warring mafias each controlled their own prison wings, but no one group dominated the entire facility, leading to near-constant battles and mass casualties.

The peak of violence came in September, when a rival launched an assault on a wing controlled by a Choneros faction. The attack failed, and the Choneros faction launched a counterattack. The fighting left 119 dead, according to the Ministry of Defense. But journalistic investigations suggest that may have been an undercount.

“Entering these wings the day after the killings, there was no smell of death, but there was a void,” said the former prison official, who was at that time working in Litoral and was one of the first to enter when the killing stopped. “It’s like there is an empty chair where someone was sitting, and no one talks about who was sitting there. Nobody says, ‘Hey, Juan was here,’ or ‘Pedro.’ No one says anything. Everyone forgets who was killed. They don’t even know their names.”

The killing was indiscriminate, and only a fraction of the dead had gang ties, according to a former member of National Assembly who participated in a Security Commission investigation into the prisons.

“Some were enemies of the other gangs, but most of the dead weren’t,” he said. “It was a message to the outside that, ‘We are the ones in control here, and we will kill whoever we want.’”

After a year of all-out war, Fito began reaching out to rivals with offers of peace. Some of these efforts, though, backfired. In October 2022, a massacre in Latacunga left 16 dead. One of the murdered inmates was Leandro Norero, a drug trafficker that had bankrolled the Lobos and their coalition of Choneros splinter groups, and one of the prime suspects in Rasquiña’s murder. Norero was stabbed to death, then decapitated, and his body dismembered. According to an intelligence report seen by InSight Crime, the police suspected he was murdered by the Lobos because he had been negotiating with Fito and the Choneros.

Despite Norero’s brutal murder, Fito’s strategy was ultimately successful. Many of the other former Choneros factions, including the Tiguerones and the Chone Killers, reunited with the Choneros. But when Fito reached out to a senior Lobos leader, his offer of peace was shot down, according to the Choneros commander, who said he took part in negotiations both inside the prison and on video calls.

“He said no, that he didn’t want to make deals with anyone, that he didn’t want peace,” said the Choneros commander.

The breakup of the Lobos’ coalition also left its mark in blood. Disputes between the Lobos and former allies led to a further series of massacres in Turi prison in Cuenca, Bellavista prison in Santo Domingo de Los Tsáchilas, the Inca prison in Quito, and La Roca prison in Guayaquil. All told, at least 94 were killed.

With the tide turning in his favor, Fito launched a public relations offensive. He appeared in a music video, which was filmed partly in La Regional. In it, his daughter and a mariachi band sing about how misunderstood he is.

“He’s a man of honor, of good character, a good person, it’s not like they say, he is a good friend, filled with humility,” they sang.

He also appeared in a video communiqué calling for peace between the gangs. Sat at a table in La Regional and flanked by heavily armed men, he offered to hand over their weapons, gesturing to his guards to lay their guns on the table.

But for all the talk of peace, the business of killing did not end: In the first half of 2023, there were a further three prison massacres that claimed 46 lives, most in the Litoral. In Ecuador as a whole, the murder rate continued its vertiginous rise, climbing to 47 per 100,000 people, a 62% increase on the year before and making it one of the most homicidal countries on the planet.

The sense of fear for the country reached its apex in August 2023, when gunmen ambushed Fernando Villavicencio – an investigative journalist turned congressman, turned presidential candidate – after a campaign event in Quito. Villavicencio’s crusading against organized crime and corruption had earned him a long line of enemies, and while the Lobos would later become the prime suspects, it was Fito who had made himself the face of Ecuador’s security crisis, and so it was Fito the authorities went after first.

The Fortress Falls

Just three days after Villavicencio’s murder, thousands of heavily armed and masked police and soldiers, backed by armored vehicles, stormed La Regional. Soon after, they could be seen hauling Fito from his cell wearing only his underwear, then bustled him from the prison with his hands over his head. Within hours, photos of a still shirtless Fito forlornly clutching the bars of his new cage in the maximum security prison, La Roca, were distributed to the media.

Back in La Regional, Fito’s transfer was met with protests, as prisoners scaled to the roofs and strung up banners calling for authorities to return their leader to his headquarters. Meanwhile, his lawyers appealed the transfer, arguing that his life would be in danger in any other prison.

The case eventually went before a panel of three provincial judges who ruled in favor of Fito, and he was immediately transferred back to La Regional. The prison authorities appealed, and the case went off the rails. After one of the judges withdrew, he was replaced by Fabiola Gallardo. At that time, she was the president of the judiciary for the province of Guayas, where Litoral, La Regional, and La Roca are located in one big prison complex. She was also for sale, according to an investigation into top-level corruption and the links between the judiciary, politics, and organized crime.

Drawing from the testimony of her assistant, who is also facing a battery of criminal charges, investigators claim Gallardo arranged a video call with Fito through his lawyer. The next day, the assistant testified, Fito sent Gallardo $6,000, a necklace encrusted with an emerald, and flowers. The hearing was rescheduled, canceled, rescheduled, and canceled again.

Then came January 7. Fito, authorities announced, had disappeared and Ecuador exploded.

As the government prepared to implement a more hard line strategy, there were riots in the prisons and bombings on the streets. Police and prison guards were taken hostage. A TV news station was overrun by armed youths live on air.

Amid the chaos, Ecuador’s new President Daniel Noboa announced the country was in an “internal armed conflict” with 22 “terrorist” organizations, among them the Choneros, and most of their allies and enemies. He ordered a manhunt for Fito, who was no longer a gangster on the run, but a terrorist at war with the state itself. And he sent in the military to recapture what was now enemy territory – the prisons, starting with La Regional.

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus