Luxury London properties tied to Azerbaijan’s president’s family concealed through offshore trust

The family and associates of Azerbaijani strongman Ilham Aliyev acquired U.K. real estate worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Are they still holding onto their property empire? Despite new transparency reforms, there’s no way for the public to know — because of the special treatment afforded to offshore trusts.

- New legislation put in place after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine was meant to peel back the curtain on secret foreign ownership of U.K. property, and achieved some success. For instance, newly available data reveals that Aliyev’s daughters own six luxury apartments in London.

- But the current ownership of 10 properties, acquired by the family for $160 million, remains unknown because they were moved into an offshore trust. Trust structures are currently exempt from public scrutiny.

- Transparency campaigners cite this “loophole” as a critical gap that undermines efforts to combat corruption. But industry groups and some politicians argue against greater transparency, citing the need to maintain the privacy of vulnerable people.

- Nearly a year after a government consultation on further reforms, there is still no clarity on how these competing concerns will be addressed.

A hotel building near the British Museum. Penthouse apartments just steps away from Hyde Park. A mansion overlooking the green expanse of Hampstead Heath. And much more.

In 2021, OCCRP revealed that a nearly $700-million collection of London real estate had been acquired by the family and close associates of Ilham Aliyev, the longtime authoritarian president of Azerbaijan. Having leveraged two decades of unchallenged political power into vast wealth, this elite group had chosen to spend a fortune in one of the financial centers of the democratic world.

The properties they purchased were owned by dozens of secretive offshore companies, hiding their ownership from public scrutiny. It was only thanks to the Pandora Papers, a leak of secret offshore documents obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, that reporters were able to link them to them to the Aliyevs.

Since then, the U.K. has introduced transparency reforms intended to make it more difficult for the wealthy and powerful to hide their ownership of property behind offshore structures.

Credit: President.az

The Aliyev family, with President Ilham Aliyev in the center. On the left are his children Leyla Aliyeva and Heydar Aliyev; on the right are his wife Mehriban Aliyeva and daughter Arzu Aliyeva.

The 2022 Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Act, also known as the ECTE Act, requires foreign entities that own or buy British land to disclose their beneficial owners in a new “Register of Overseas Entities.”

This should make finding any property’s owner a matter of performing a simple search of the online database run by Companies House, the U.K. corporate registry. But how far has transparency increased in practice? Does the new register actually reveal whether the Aliyevs still hold their vast London property portfolio?

We decided to find out. Reporters from OCCRP teamed up with researchers from Transparency International UK, an anti-corruption advocacy group, to reexamine the 23 London properties our earlier investigation had linked to the Aliyevs. In theory, the “Register of Overseas Entities” should publicly name the human beings behind the faceless offshore companies that hold the properties.

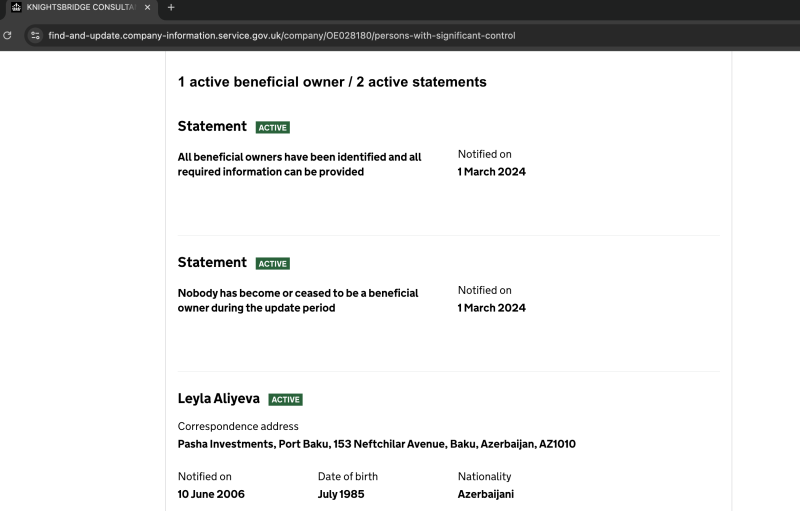

In six cases, it does: The Register publicly reveals for the first time that President Aliyev’s daughters, Leyla and Arzu Aliyeva, personally own six luxury apartments just across the street from Hyde Park.

Credit: President.az

President Aliyev’s daughters Leyla Aliyeva (left) and Arzu Aliyeva (right).

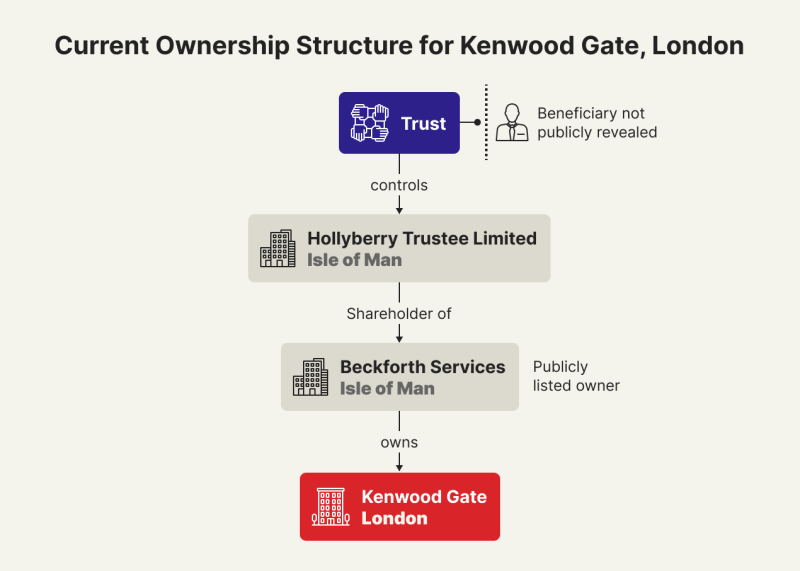

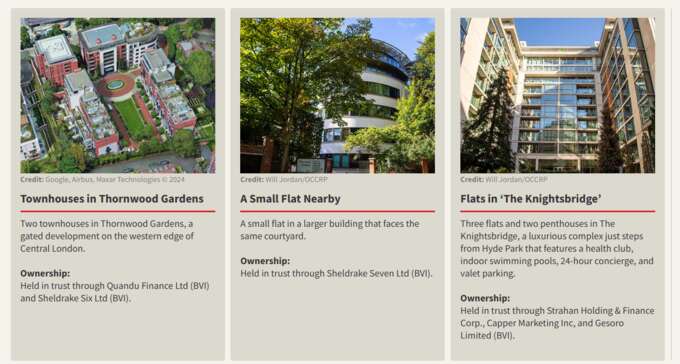

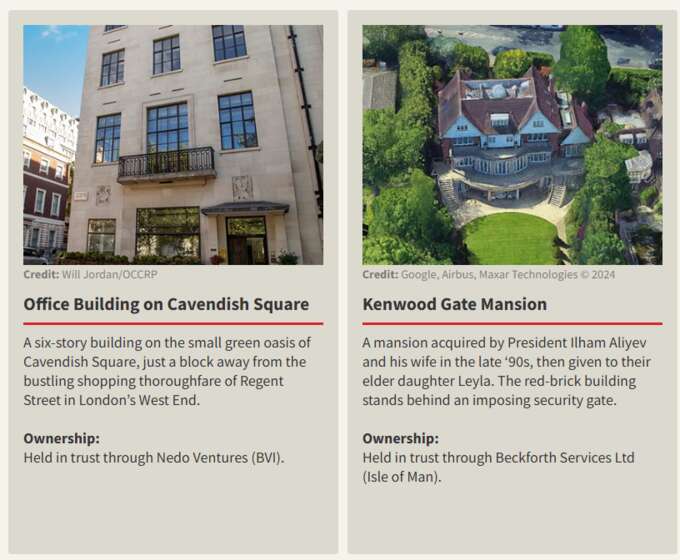

But the Register fails to establish who ultimately owns 10 properties the Aliyevs and their associates had acquired for $160 million: the Hampstead Heath mansion, two townhouses, multiple flats and penthouses, and a six-story building in Central London. It only reveals that they are owned by a trust registered in the Isle of Man.

Trusts are arrangements that allow an asset to be managed by one person for the benefit of another. There are many legitimate reasons to use a trust, like managing the wealth of someone who cannot do so themselves because they are underage or incapacitated.

But, as the case of the Aliyevs demonstrates, trusts can also shield controversial and wealthy figures from scrutiny.

The issue is not confined to the U.K. Studies by the World Bank, the OECD, and other organizations have highlighted the use of trusts by corrupt actors across the world to disguise their involvement in corporate structures.

But it has emerged as a key bone of contention between British transparency campaigners and privacy defenders as the country tries to make its financial system less vulnerable to dirty money. According to research by Transparency International published in 2023, 7,000 offshore companies holding over 20,000 properties across the U.K. are owned by trusts — a quarter of all the companies on the Register. Although the ECTE Act requires the trusts to reveal their beneficiaries to Companies House and tax authorities, there is no functional way for journalists, transparency advocates, or the public to gain access to the information.

Credit: Edin Pašović/OCCRP

Credit: Will Jordan/OCCRP

Among the Aliyev properties whose ownership is now hidden behind a trust are four flats and two penthouses in The Knightsbridge, an elite development just steps from Hyde Park.

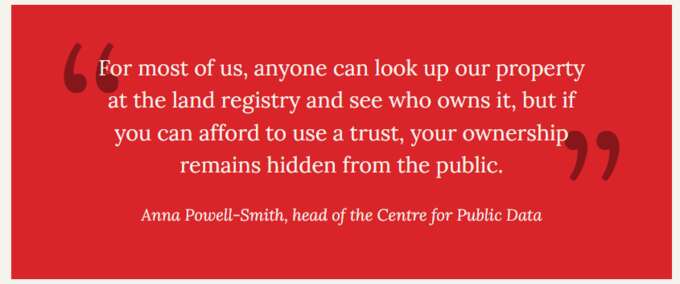

Anna Powell-Smith, head of the London-based Centre for Public Data, described the situation as a “two-tier system,” in which wealthy people can pay to set up structures that conceal their property ownership from the public.

“For most of us, anyone can look up our property at the land registry and see who owns it,” she explained. “But if you can afford to use a trust, your ownership remains hidden from the public. We need full transparency for the housing market to work properly, and to tackle corruption and money laundering.”

Since the ECTE Act passed, transparency advocates like Powell-Smith have kept arguing for trust information to be made publicly available, asking the government to close what they see as an obvious loophole.

“The reforms in 2022 after the invasion of Ukraine were designed to stop London property being used in ways that weren’t transparent and that damaged Britain’s reputation,” she said. “And by leaving loopholes for trusts, the law isn’t working as intended.”

But industry groups have pushed back, arguing that trust beneficiaries deserve additional privacy protections since trusts are often used to hold assets for vulnerable people, including minors.

When another bill to combat dirty money was passed last year, a proposed amendment that would have allowed Companies House to publish the trust information that is submitted to the Register of Overseas Entities was not adopted.

Earlier this month, the U.K.’s Department of Business and Trade did propose new regulations that would enable members of the public to request information about trusts from Companies House. But there would still be limitations on these requests — and in order to make one, you would need to know the precise name of the trust, which may not be publicly available.

Powell-Smith argues that there are already sufficient privacy protections for property owners, without creating exceptions for trusts.

“There is no clear reason why trust beneficiaries should have more privacy than other owners of property, as is the case now,” she said. “I do not believe any of the industry stakeholders have a strong argument against that. There are already protections for vulnerable property owners which could be applied to vulnerable trust beneficiaries. The current setup simply leaves loopholes to be exploited by those seeking secrecy.”

Joe Powell, a Labour MP who has pushed for greater transparency to tackle dirty money in the U.K., said the fact that the Aliyev properties had been moved into a secret trust exposed "glaring loopholes in the U.K.’s transparency framework for property ownership."

“This lack of transparency leaves the public completely in the dark about who truly owns these properties,” he said. “It’s precisely these loopholes that make the U.K. a playground for the global elite to park their cash here while evading accountability.”

Azerbaijan’s presidential administration did not respond to requests for comment, but President Aliyev has previously attributed his wealth to success in business.

In an interview published on the presidential website in 2021, shortly after OCCRP revealed the extent of his family’s London property holdings, he acknowledged that he was “not a poor man” when he became president, but said this was due to his business achievements. (The son of Azerbaijan’s first post-independence leader, Aliyev served as a vice-president of Azerbaijan’s state oil company before succeeding his father as president in 2003.)

“Unlike some other people in the West who dedicate all their fortune to their cats and dogs, in Italy and Azerbaijan we value family values,” he said at the time. “Therefore, I transferred all my business to my children.”

New Revelations On Speakers’ Corner

The clearest new information about the Aliyevs’ property empire in the Register of Overseas Entities concerns one of the first pieces of London real estate ever tied to the family: a five-story luxury apartment building across the street from Hyde Park.

In 2015, OCCRP reported that Leyla Aliyeva, the Azerbaijani president’s then 29-year-old elder daughter, was one of the directors of the British company that managed the building, worth over $33 million.

The house on Speakers’ Corner

At the time, one of OCCRP’s Azerbaijani reporters, Khadija Ismayilova, was in jail in Baku on politically motivated charges related to her journalism. It is ironic, then, that the building overlooks Speakers’ Corner, part of Hyde Park famously dedicated to hosting demonstrations of raucous free speech.

But aside from Aliyeva’s signature on a corporate document, the nature of her family’s connection to the building was never established. The luxury apartments inside were owned by companies registered in the British Virgin Islands, where their owners are not revealed, and the corporate trail ended there.

After the passage of the ECTE Act, however, those companies were required to file their ultimate beneficial owners in the Register of Overseas Entities. They have done so, revealing that five properties in the building belong to Leyla Aliyeva outright, while another belongs to her younger sister Arzu.

In this case, the U.K.’s transparency reforms functioned as intended, allowing the public to see for the first time who really owned these properties.

Leyla Aliyeva’s name appears in the ‘beneficial owners’ section of the Companies House entry for Knightsbridge Consultancy Limited, the British Virgin Islands-registered company that owns one of the apartments in the house on Speakers’ Corner.

Trust Hides True Ownership of Multiple Properties

In another six cases, the companies behind the properties listed new beneficial owners who appear to have no relation to the Aliyevs or their associates, suggesting that the properties were sold after the publication of OCCRP’s 2021 story.

But the beneficial ownership of 10 high-end London properties remains impenetrable.

Aliyev-Linked Properties Held in Offshore Trust

These properties, once owned by members of the Aliyev family and their close associates, are held by an offshore trust, making it impossible to determine their beneficial owners.

These properties are owned by eight offshore companies. While most have listed their beneficial owners as required under the new rules, their filings are a dead end. Each company names its owner as “Hollyberry Trustee Limited,” a trustee company registered in the Isle of Man.

Looking up Hollyberry’s owner reveals only who set up the arrangement: a company called Mann Made Group, which advertises itself as a “leading client-focused trust and corporate service provider” in the Isle of Man.

The actual beneficiaries of the properties — the people who can use them, earn rental income from them, or receive the proceeds of their sale — are not named in connection to them on any public documents.

While the ECTE Act already gives privacy to the beneficiaries of trusts, the Isle of Man, a tax haven in the Irish Sea, offers additional advantages. For example, unlike many other jurisdictions, it does not recognize foreign court orders over trusts. Isle of Man law does require service providers like Mann Made Group to conduct in-depth financial checks if dealing with political figures and their families or associates, to mitigate money laundering risks. Mann Made Group did not respond to requests for comment.

Although it’s impossible to know for sure who benefits from the mysterious Manx trust, there are clues that the properties remain linked to the Aliyev family or their associates.

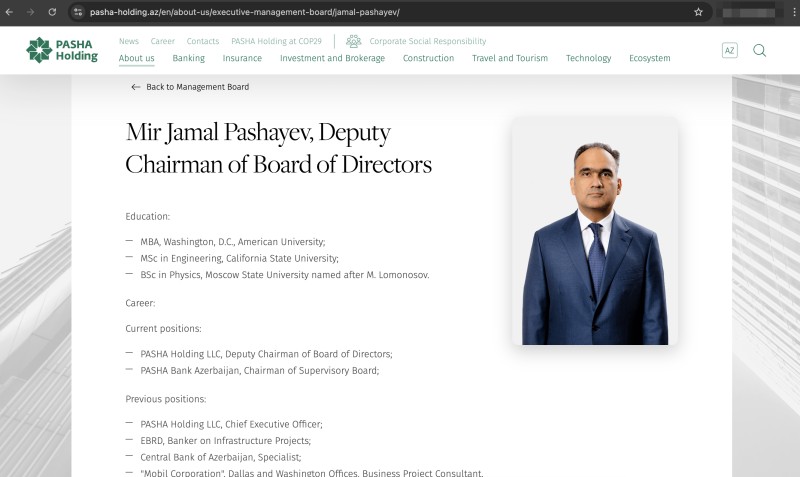

For 9 of the properties, the Register of Overseas Entities lists the same person as having “significant influence or control” over the offshore companies that own them: Mir Pashayev.

The partial date of birth information displayed for him on Companies House, as well as the correspondence address, matches the known data of Mir Jamal Pashayev, a cousin of President Ilham Aliyev’s wife.

The 54-year-old-banker is closely linked to the Aliyev family’s business interests. He is a board chairman of Pasha Bank, a major lenderowned by the president’s daughters Leyla and Arzu, and deputy chairman of the board of directors of their entire Pasha Holding business conglomerate, which spans interests in banking, insurance, and construction.

Pashayev’s name has previously emerged in connection with the Aliyevs’ U.K. properties on another occasion: In October 2014, he took over from Leyla Aliyeva the directorship of the company that manages her mansion on Speakers’ Corner.

Taken together, the evidence suggests that Pashayev could be playing an administrative role in the corporate structures that hold the London properties on behalf of their ultimate beneficiaries, who remain shielded thanks to trust privacy rules. Pashayev did not respond to requests for comment.

Tocki Trust

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus