Blood and Ore: Mexican cartel violence silences mining opponents

The abduction of a Mexican community activist who campaigned against an iron ore mine owned by New York-listed Ternium has shone a light on how local cartels benefit from the presence of mining companies in the region.

In January last year, a 71-year-old Indigenous activist named Antonio Diaz left a community meeting in western Mexico and disappeared with his lawyer into the night. Police soon found a white Honda truck, shot up and abandoned in a small town in a neighboring state. But there was no sign of the men.

In the distance loomed the Sierra Costa mountains, home to the vast, dusty expanse of the Las Encinas iron mine. For several years, the two men had been fighting an uphill battle against the mine, which locals claim has devastated wildlife and polluted the water supply.

Las Encinas was run by Ternium S.A., a $6.2-billion multinational steel company with shares listed in New York, headquarters in tax-friendly Luxembourg, and customers such as Tesla, General Motors, and the Mexican government.

The mine, locals allege, offers more money-making opportunities for local cartels, which often charge fees to operate on their turf and in the past have extorted a portion of the royalties villagers received from the mine’s profits.

Those who oppose the mines can become targets for the cartels. In recent years, more than half a dozen people who had challenged Ternium’s mines have been kidnapped, murdered, or disappeared. In one community, an activist was kidnapped and, according to filings made by his lawyers, forced to drop a lawsuit against a mine co-owned by Ternium and steel giant ArcelorMittal.

Activist Diaz did not consider the mining companies to be blameless. At the end of 2022, he wrote to Mexico’s then-President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, imploring him to launch an investigation into Ternium. He accused the company of having hired armed groups in the past to “attack and repress Indigenous people” and said its employees had threatened the mine’s opponents.

Ternium condemned “any kind of violent response against the community” and rejected any direct or indirect association “with violent cases…or the disappearance of any people.” Ternium said it has “deep concern over the disappearance” of Diaz and his lawyer, and said the pair had engaged with company officials in a spirit of “openness, freedom, respect, and personal appreciation.”

ArcelorMittal said it operates “within the law, adhering to high international standards regarding human rights and environmental respect.” The company strongly condemned “violence and criminal activity in Mexico” and firmly rejected any direct or indirect association with or responsibility for the perpetrators of violence.

At times, it wasn’t clear Diaz would be able to continue his campaign. After one meeting with Ternium representatives, he inexplicably cut off contact with the other activists in Aquila. A few weeks later, he resurfaced to join an assembly in December, where he alleged that Ternium officials had threatened to retaliate against its opponents. Ternium did not respond directly to Diaz’s claim, but said “any association of Ternium with the potential hiring or involvement of armed groups is entirely baseless and absurd.”

Then the mood took a surprising turn. Diaz and his lawyer, Ricardo Lagunes, showed up at the January assembly to tell attendees there had been a breakthrough: It looked, they said, like a local court would soon let elections move forward to replace community leaders the activists believed were allied with Ternium. The pair were also hopeful that the court would release millions of pesos in rent Ternium owed to the community but had placed in escrow.

An ArcelorMittall steel factory in Luxembourg.

Some of the activists hung around after the meeting, sharing a few beers and a bite to eat with Diaz and Lagunes. “The good news left us with a good taste in our mouths,” one later told police.

Diaz and Lagunes headed toward Lagunes’ home in the neighboring Colima state. But they never made it — and have never been found.

A member of a major cartel would later tell police he had helped abduct the pair. The reason, he told police, was that the men were “f***ing with the mines.” He was murdered before he could stand trial.

Cartel Control

Ternium started life as an Italian company called Techint, founded in 1945 by an official who served in senior positions at state-run firms under the Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini.

The firm relocated partly to Argentina over the coming years, and over time its operations in Latin America — particularly Mexico — became central to its business. The company secured millions of dollars in government contracts under López Obrador, and last year its work in Mexico contributed over half of its $18 billion in net sales.

Today, Ternium plays a crucial role in the supply chains vital to manufacturers relocating operations to Mexico for easier access to U.S. markets. The company plans to invest nearly $7 billion in Mexico, where U.S. automakers are spending heavily to develop electric vehicle plants. Tesla CEO Elon Musk visited Ternium’s factory in the northeastern Nuevo Leon state last year.

But operating in Mexico has come with a dark side. Criminal groups got mixed up in the mining sector after former President Felipe Calderón launched a war on cartels in 2006, prompting the narcos to diversify beyond the drug trade. Cartels robbed and extorted companies, started illegal mining operations, and sold illicit iron ore to legal companies.

In January, the head of the industry body for mining engineers, Luis Humberto Vázquez, bluntly told local media: “We’ve been forced to pay organized crime for protection.”

Most of the area where Ternium operates is dominated by the Jalisco Nueva Generación Cartel, which the U.S. Department of Justice has called “one of the five most dangerous transnational criminal organizations in the world.” The cartel has been under U.S. sanctions since 2015, and its leader, Nemesio “El Mencho” Oseguera Cervantes, has a $15 million bounty on his head.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency is offering up to $15 million as a reward for information leading to the capture of Nemesio “El Mencho” Oseguera Cervantes.

The cartel is able to control communities and businesses by being “more ostentatiously violent than anyone else around,” Vanda Felbab-Brown, a security expert at the Brookings Institution, wrote in a 2022 op-ed.

“Brazenness, brutality, and aggressive expansion are its signature approach,” she wrote. Beyond its core business of drugs, the cartel acts “as a tax master and sometimes franchise licenser” of legal companies in its territories.

Cartel control means that, for businesses working in rural areas, it’s “a binary scenario where you pay up or you piss off,” Falko Ernst, a senior Mexico analyst and organized crime expert for the International Crisis Group, said in an interview. Payments to organized crime are seen as “just an added cost of conducting business on the ground.”

Antonio Diaz’s Abduction

Antonio Diaz, a member of the Nahua Indigenous people, was born in Aquila into the deep poverty of 1950s Mexico.

As a seven-year-old, he slept in an outdoor cot on a farm, working from 4 a.m. to pay his keep before school. He later won a scholarship to attend the nearest high school, about 80 kilometers away, where he would walk every couple of weeks.

He became a teacher, and then rose to become the administrator of a school district near the state capital of Morelia, a seven-hour drive from Aquila. But he continued to visit his hometown to support the community’s efforts to fight the Las Encinas mine’s expansion.

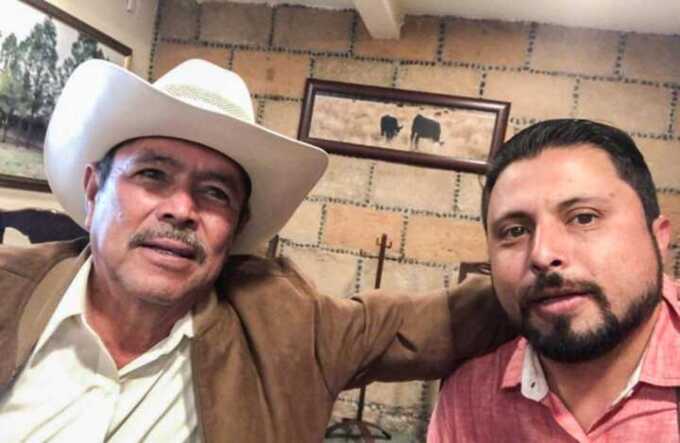

Antonio Diaz.

The ecological damage locals attribute to the mine is visible in a trickling stream in the valley below the town, which activists say was once a gushing river where people would fish and bathe. Now there’s seldom enough water for many crops and residents believe the supply has been contaminated by toxic waste.

Ternium said it complies with all “environmental laws and conditions.”

Cartel violence has menaced the area for more than a decade. In just the second half of last year, two mutilated corpses were dumped near Aquila in separate incidents — one dismembered and another showing signs of torture. (Neither had any connection to Ternium’s mine.)

So-called “hawks” — cartel spies who report unusual activity to the narcos — hang around the town’s central square. Few locals dare leave home after dark. “We feel imprisoned,” said one resident.

In 2019, Diaz began working with Ricardo Lagunes, a lawyer three decades his junior, to undo the election of someone they considered to be a Ternium ally as leader of the local Nahua community.

Lagunes, who had previously defended members of an Aquila militia formed to protect the town against cartels, helped the activists win a ruling to overturn that election in 2021. But authorities didn’t hold a new vote.

Ricardo Lagunes.

Frustrated by the stalemate, community activists protested outside the courthouse in January 2022. A funeral wreath was later hung on the door of the courthouse, which activists interpreted as a threat — from local leaders, narcos, or both.

The febrile atmosphere persisted into the following January, when Diaz and Lagunes attended their final community meeting.

Along their drive home, the men were ambushed by a group of about ten gunmen and “hawks,” according to testimony given to police.

One of the hawks, Javier Puntos, told police under oath that the men had photos of the two activists and the white Honda truck they were driving in. Jalisco Nueva Generación’s local bosses had said they “would f***ing end us” if the two men escaped, Puntos said.

When the car approached, the gunmen fired a few shots, pulled the two men out of the vehicle, and drove off with them, Puntos said.

”Afterward, I learned they kidnapped them because they were going around f***ing with the mines,” Puntos said, though it’s not clear if he provided evidence of any involvement by Ternium. (Part of Puntos’ testimony was first reported by Mexican outlet A Donde Van Los Desaparecidos.)

A couple of days after the kidnapping, a video circulated on social media of a man prosecutors identified as Diaz wearing a green T-shirt, his arms seemingly tied behind him, and his face mostly obscured.

Video circulated on social media allegedly showing Antonio Diaz.

Puntos said that after the authorities began investigating, the cartel kept the men’s whereabouts secret from him and the other hawks. There are operatives “who hide bodies,” he told police. “After killing them, sometimes they bury them in cemeteries, or they burn or cook them, or they hide them in their ranches.”

For unclear reasons, the authorities released Puntos after his police interview. He was found dead soon after. (Officials at Mexico’s office of the attorney general did not respond to a request for comment on the release of Puntos.)

Not Just Aquila

Aquila was not the only community that faced threats and violence while campaigning against a Ternium mine.

‘Almost Absolute Impunity’

Cartels and their enablers enjoy “almost absolute impunity” in Mexico, according to the United Nations. About 100,000 people have disappeared in the country since 2007. But as of 2021, only about two to six percent of cases had resulted in prosecutions.

In this context, the disappearance of Diaz and Lagunes received an unusual degree of international attention, partly thanks to the resources and connections of the men’s families.

After the United Nations called on Mexico’s government to investigate, two men were charged over their disappearance last spring: Jose Cortes Ramos, the former leader of Aquila whose administration pushed through an expansion of the Las Encinas mine, and a young man who was caught trying to pawn Diaz’s phone.

Ramos pleaded not guilty at a pre-trial hearing, but the case has since been held up by procedural challenges by his lawyers. Messages sent to Ramos’s number went unanswered. Ramos’s cousin acknowledged receipt of questions from reporters but did not send written responses.

In September last year, the community in Aquila was finally able to hold the election that Diaz and Lagunes had been fighting for. A community member who had worked for Ternium for years won the vote.

Ternium did not directly comment on the election, but said it engages “with the communities surrounding our operations, working to address their concerns in a transparent and constructive manner,” and that it has “a good working relationship” with the Aquila community.

Diaz, himself, had long been prepared to sacrifice everything for his Nahua community. “The pride of my life is to always be on the side of my comrades, my Indigenous brothers,” he said in a short video shared by his son. “I will offer all my every effort, my work and my life to defend our race.”

Analy Nuño contributed to this report.

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus