A cold war is raging inside the Sinaloa cartel

On a deserted, unpaved street in the rural community of La Loma, a young man in his twenties stands on a street corner in the early hours of a cloudy morning. On his hip he holds several walkie-talkies and at least one pistol.

His eyes scan his surroundings, registering who is walking down the street, who is heading for the cornfields on the outskirts of town, and anyone behaving suspiciously. If unknown cars pass by, the young man radios his colleagues, and two people on motorcycles immediately appear to chase the vehicle down and make sure they are not intruders.

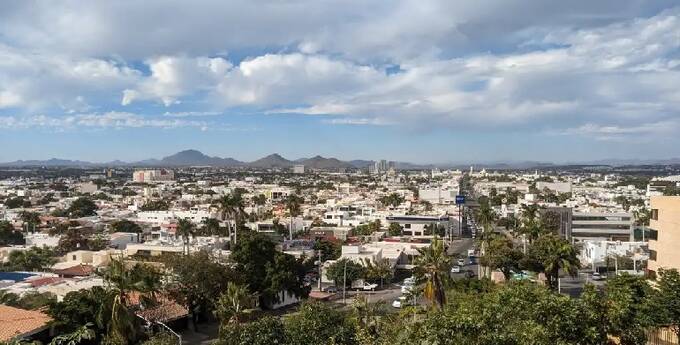

La Loma has eyes like this everywhere. With just over a thousand inhabitants, the town lies next to Federal Highway 15D, which, according to several sources consulted by InSight Crime, is one of the invisible borders that carve up the areas controlled by either the Mayiza or the Chapitos here in Culiacán, the capital of the state of Sinaloa.

Both groups are factions of the Sinaloa Cartel. The first is linked to Ismael Zambada Garcia, alias “El Mayo,” who was arrested on July 25 at a private airport in New Mexico in the United States, and will be tried in federal court on various drug trafficking charges. The second group includes four of the sons of Joaquín Guzmán Loera, alias “El Chapo,” who has been behind bars in the United States since 2017.

Following the capture of El Mayo, tension between the Mayiza and the Chapitos factions has worsened in Culiacán, which has historically been the epicenter of the Sinaloa Cartel’s activities. The version currently dominating international discourse — and the one believed by most sources consulted by InSight Crime — suggests that Zambada was betrayed and taken against his will to US authorities by Chapitos member Joaquín Guzmán López, also arrested that day when he turned himself in.

This has fueled speculation about a potential escalation of violence motivated by revenge or settling of scores. The Mexican army, for example, announced the deployment of more than 200 soldiers to Sinaloa the day after the capture to “guarantee security and allow all societal activities to continue.”

Warning Shots

Three weeks later, there are some signs of violence. On August 17, for example, seven people were killed, including at least three Mayiza operatives, in the municipality of Elota. And on August 2, the army killed six people during an alleged confrontation in La Loma. At least one of them reportedly had no links to organized crime and worked in the corn fields nearby, his family told InSight Crime.

During interviews with several people in La Loma, few dared to talk about the incident or its possible link to the fallout from El Mayo’s capture. Under constant surveillance by “punteros” like the young man, the tension and uncertainty about the future was palpable.

“Who knows what is going to happen, but right now I don’t trust anyone,” a woman in her 40s, who asked not to reveal her name for fear of reprisals, told InSight Crime.

These perspectives are reflected in the underworld. InSight Crime interviewed five people involved in various stages of drug trafficking in Sinaloa. All were aware of the current tension between the Chapitos and the Mayiza and had adopted more cautious stances as a result.

However, like the inhabitants of La Loma, they shared the uncertainty about when this tension might flare up. Engaging in a frontal war in their own stronghold did not seem to be an attractive option. At least, for now.

The Iron Curtain in Sinaloa

The departure of El Mayo has reportedly left Ismael Zambada Sicairos, alias “Mayito Flaco,” in charge of La Mayiza. He is the only son of El Mayo who is allegedly still operating in Culiacán, following the arrest of several of his brothers. Some of them have served sentences in the United States, where they have collaborated with the justice system.

It is not clear why El Mayito Flaco has not reacted directly to the Chapitos’ alleged betrayal. However, sources who spoke to InSight Crime believe it could be an attempt to keep a low profile and avoid attracting government attention, or because he does not yet have the resources to take on the Chapitos, who have amassed a large number of gunmen in their ranks over the years.

Regardless of the reason, the dividing lines between the two factions — historically linked by ties of marriage and close friendship known as compadrazgo — are becoming more pronounced, according to sources. This has turned “border” communities, such as La Loma, into points of high tension.

“There are no words for what the Chapitos did,” said one methamphetamine and fentanyl trafficker in a town outside Culiacán, also close to the dividing line, who spoke to InSight Crime on condition of anonymity. “Of course a lot of us are angry.”

The divisions could even be replicated in the prison system. One person who worked independently in fentanyl production in Sinaloa and is currently held in Aguaruto Prison in Culiacán told InSight Crime that choosing sides between the two criminal groups has become more important for those behind bars.

“There’s a lot of fear and panic with the new rules that [El Mayito Flaco] might put in place,” he said.

Fight or Flight

Ultimately, a decision on whether or not to respond to the alleged betrayal of El Mayo will be made by the Mayiza’s top leadership. Meanwhile, some of those working in the lower echelons of the organization are adapting and remaining particularly vigilant, like the punteros of La Loma.

For some, these measures have been drastic. One man who oversees several clandestine laboratories and has worked with both the Chapitos and the Mayiza, spoke to InSight Crime on condition of anonymity and said the current situation forced him to leave Sinaloa indefinitely.

“Right now I can’t go back. I have to wait for things to stabilize,” he said during a telephone interview. His main concern is that he has collaborated closely with both sides, which puts him in a delicate situation should a war break out.

The methamphetamine and fentanyl trafficker on the outskirts of Culiacán added that he also knows several people who have left Sinaloa for similar reasons.

Those who decide to stay in Culiacán are trying to be more discreet about their illegal activities. All sources consulted by InSight Crime agree that an increase in violence between the Chapitos and the Mayiza would be bad for their business. It would bring greater pressure from the government, require the redirection of resources towards the purchase of weapons, and generate a deterioration in the relationship with the local population.

A synthetic drug producer working in another Mayiza-controlled town on the outskirts of Culiacán, for example, commented that the increased presence of the army after the capture is already causing him problems, so he thinks it unwise to attract more attention.

“There is a high government presence around here now. That worries me. I have to watch my back better,” he said at a meeting in the living room of his house, where he made sure to close all the curtains so that no one would see him meeting with people from out of town.

Mayo Zambada himself reportedly called for peace to be maintained in Sinaloa and for violent reactions to be avoided in a letter published by his lawyer.

“We have been down that road in the past and we all lost out,” the letter, originally published in English, said.

Eventually, war might be inevitable, especially since the Chapitos’ alleged betrayal of El Mayo implies a breaking of “codes” that the various factions of the Sinaloa Cartel have traditionally respected to keep the peace at home.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen, but if they attack us, here the Mayiza has several armored trucks ready,” said the synthetic drug trafficker in the “border” town.

“They just need to give the order.”

Proxy War on the Border

Some 1,500 kilometers from Culiacán, the situation could be different. In the area near the US border, in the states of Sonora and Baja California, the Chapitos and the Mayiza have been engaged in a proxy war for years through their respective armed groups: the Salazar and the Rusos.

The disputes began after El Chapo’s capture, and center mainly on control of border corridors and local drug consumption markets, according to a security official who spoke to InSight Crime on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly on the subject.

In recent weeks, signs of a possible uptick in tensions between the two groups have emerged. On July 31, for example, the Chapitos-associated Salazar group allegedly posted a message outside the border city of Mexicali, threatening authorities for allegedly collaborating with the Rusos.

But even if this war escalates, the decentralized nature of drug trafficking, especially of synthetic drugs, means that there will not necessarily be disruptions in supply across the border. In addition to the Chapitos and the Mayiza, there are dozens of criminal networks in the country that will continue to operate.

Two individuals involved in fentanyl production and transshipment in Baja California, as well as a methamphetamine wholesaler in the western United States, told InSight Crime that their workflow has not slowed in recent weeks.

“I am not affected by [El Mayo’s] capture. If we don’t work with him, it will be with someone else,” the wholesaler said.

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus