All the President’s Men: State projects handed to apparent proxies in Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov has drastically decreased transparency into public spending, even as he has launched an ambitious new series of state projects intended to show off his government’s power.

But behind the scenes, the projects are being implemented by companies owned by people who appear to be close to the president himself.

In April 2022, a year and a half after becoming president of Kyrgyzstan, Sadyr Japarov announced he was fed up with the country’s government procurement system and would sign a law to eliminate it.

“Don’t worry,” he reassured Kyrgyz citizens in a Facebook post explaining the change. “From now on, mechanisms will be in place to prevent corruption.”

He didn’t explain what those would be, but used the example of a school-building project in Bishkek, the Kyrgyz capital, claiming he would save money and get the schools built to a higher standard by taking the construction under his “personal control” instead of issuing public tenders.

It was a frequent refrain Japarov has used since taking power: Kyrgyzstan was hopelessly inefficient. Public procurement rules were a “headache.” He would streamline processes, “take responsibility,” and get things done.

But experts and regional observers say he has tried to do this through a series of anti-democratic power grabs, including ramming through constitutional changes that allowed him to lead the government, make ministerial appointments, and propose laws directly to parliament.

A veteran of Kyrgyzstan’s boisterous political scene, the president had been in jail — convicted of taking a local official hostage years ago — when the 2020 Kyrgyz Revolution broke out. He was freed by his supporters and quickly seized power.

Before that, Kyrgyzstan had been unique among the post-Soviet states of Central Asia for its relatively open political climate, with a vibrant media scene and vigorous civil society that had flourished since 2010, when a parliamentary form of government was introduced and presidential powers reduced. But Japarov has centralized so much power in his own hands that he has effectively undone all this, regional experts say.

“He changed the constitution to basically weaken the role of the parliament, therefore weaken the role of the political parties, and enforce his own power, the power of his administration and of the executive,” said Asel Doolotkeldieva, an expert on Kyrgyzstan and non-resident fellow at George Washington University, on a recent episode of the Talk Eastern Europe podcast.

“He then moved to silence the society. Today, ordinary citizens get sentences for ridiculous things such as simply posting information on social media. You can get up to five years for posting harmless news.”

Japarov’s initiatives have included the changes to the Law on Public Procurement he boasted about on Facebook in April 2022. State-owned enterprises are now allowed to completely bypass tender procedures and purchase goods and services directly from suppliers, at their own discretion. They don’t have to publicly advertise for suppliers or contractors like they did before. Around the same time, the government shut off access to details about public spending it had previously made available on a website frequently used by journalists, Open Budget.

Altogether, these changes drastically diminished public oversight over state spending, prompting a coalition of civil society groups and even the International Monetary Fund to warn that they risked increasing corruption.

As this was happening, the president also increased the role of a state body directly under his control, the On paper, the Directorate has a narrow mandate — to provide “financial, material-technical, transportation, social, recreational and medical support” to the president and some of these tasks also to the parliament and cabinet of ministers. Under past administrations, it has stuck to that script. But in its new form under Japarov, its power has rapidly expanded.

A newly appointed head of the directorate, Kanybek Tumanbayev, has been tasked with overseeing a series of ambitious new national projects designed to demonstrate how the country is developing under Japarov’s rule: A huge new Presidential Palace, a new airport building and runway extension in the eastern city of Karakol, tourist infrastructure in a national park, and social housing projects.

None of these were put out to public tender except the airport — which Japarov later halted, saying that officials had offered too much money for the work.

He explained his reasoning in an interview with local outlet Kabar.kg:

In 2021, I instructed the management of the country’s airports to carry out reconstruction and renovation of the facilities and resume domestic flights. One day I decided to find out how the work was going. They said that a tender had been announced, and that tomorrow it will end. Hearing this, I told them to suspend the process and bring me the estimate submitted for the tender. After checking the data they presented, it turned out that for the reconstruction of the Karakol airport alone, the sum was inflated by $10 million. We immediately canceled the tender. …. Now we’re building everything ourselves, having saved $10 million in the budget.

But Japarov never actually announced who would build the Karakol airport, or how much it would end up costing.

Bakyt Satybekov, an expert on public finance in Kyrgyzstan and a former chair of the Ministry of Finance’s Public Council, said a complex infrastructure project like an airport should be built transparently by experienced contractors, with clear documentation available to the public.

“Construction work must be done by specialized construction companies … I don’t know how they ‘do it themselves,’ plus in any case there should be [publicly available] project design and budget documentation,” he said.

“There are safety issues,” Satybekov added of the airport project. “This is not like building yourself a barn.”

Japarov, Tumanbayev, and the Presidential Administrative Directorate did not respond to detailed questions from reporters on the findings of this story. Neither did the management of the Karakol airport, or the owners of the other companies named in the investigation.

Kanybek Tumanbayev: A Man of Many Presidents

Before being hand-picked by Japarov to lead his directorate, Tumanbayev, 42, had already been a behind-the-scenes figure for two previous Kyrgyz presidents.

In 2015, he ran for parliament as a member of the Social Democratic Party of Kyrgyzstan, the party of then-President Almazbek Atambayev. His low position on the party list didn’t land him a seat, but there are indications that he had a close relationship with Atambayev. Corporate records show that, after leaving office in 2017, Atambayev took over ownership of two TV stations previously owned by Tumanbayev. A source who worked at one of the companies and had firsthand knowledge of how their management was structured, speaking on condition of anonymity, told reporters that Tumanbayev had appeared at the office and had been understood by staff to be a proxy for Atambayev all along.

Even before the transition from Atambayev to his successor Sooronbay Jeenbekov, Tumanbayev was already forging ties with the future president. In 2017, he worked for Jeenbekov’s presidential election campaign, and in 2020, he made another attempt to enter parliament, this time with the pro-government party Birimdik.

He failed again, but it wasn’t a problem for long: In October 2020, widespread dissatisfaction with election results fueled by allegations of rigging culminated in a revolution. Mass protests toppled Jeenbekov’s government, and Sadyr Japarov assumed power. A year and a half later, Tumanbayev was appointed head of his Presidential Administrative Directorate.

Local journalists attempting to report on these projects have been threatened — or worse. When Radio Azattyk reported in September 2023 that Tumanbayev had personal links to contractors building the Presidential Palace, state television blasted the report and accused the news outlet of “distorting” the facts. Another media outlet, Sputnik, was asked to apologize for “creating a public panic and undermining the dignity of the named citizens” after publishing a similar story in January 2023.

And Temirov Live, an OCCRP member center that was investigating the projects of the Presidential Directorate, has been effectively shut down after a widening crackdown this year left 11 of its journalists fighting charges of inciting mass disorder, with some awaiting trial in jail.

Now, reporters from OCCRP have come together with colleagues from Temirov Live and Kloop to finish their work. Together, we identified at least 11 projects being built by the Presidential Administrative Directorate whose contractors were completely hidden under the new veil of government secrecy that has descended on Kyrgyzstan. Reporters were able to access information on the cost of only six of the projects, which total $137 million. It was impossible to determine how much the government was spending on the other five.

Reporters then looked for clues about what companies might be involved. Although it was no longer possible to obtain the official procurement data, they pored over all the records it was possible to collect, including incorporation documents and land records. They also analyzed social media posts by some of the people who appeared to own or manage the companies, finding many links between them — and to Tumanbayev.

Finally, they managed to track down an insider who is familiar with how the Presidential Administrative Directorate operates under Tumanbayev. Over the course of multiple interviews, the insider — who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation — provided inside details of how some of these projects were managed.

He explained that some of the most important state projects had been contracted out to companies controlled by people close to Tumanbayev — or, in a few cases, to Japarov himself. The insider said Tumanbayev retained true control over all these companies and gave orders to their nominal directors and shareholders.

“Kanybek [Tumanbayev] only gives orders to [alleged proxy] Baatyrbek [Jantayev], and Baatyrbek does everything,” the insider said. “[Tumanbayev says,] ‘Appoint that person a director,’ and he will do it.”

Tumanbayev did not respond to requests for comment.

The Companies

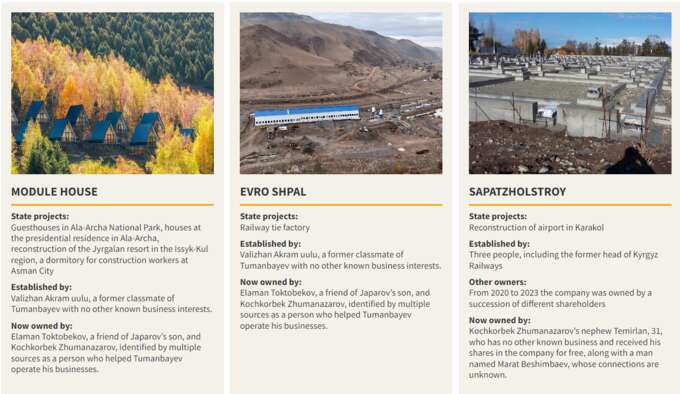

Reporters identified five companies that won contracts to build state projects under the Presidential Administrative Directorate. They all have links to people connected to President Sadyr Japarov or Directorate Head Kanybek Tumanbayev.

In some cases, the insider provided new information that reporters were able to verify; in others, he confirmed what reporters had already learned through documents or social media posts.

Take the case of the Karakol airport. After the president canceled the tender and announced that “we will build everything ourselves,” no public information was ever made available about the company he had chosen to work on it.

But the source provided a name: “Sapat Zhol is the company,” he said. “Temirlan works there. I’ve forgotten his last name right now.”

He explained that Temirlan was the young relative of a close associate of Tumanbayev. “He does everything there [at the airport],” he said.

Reporters identified the man as Temirlan Zhumanazarov and began watching for signs of him. They soon noticed him in footage alongside Tumanbayev during his visit to the airport construction site.

Then, state television interviewed one of the construction workers there and identified him in subtitles as a “Sapat Zhol” worker. Learning the company name helped journalists link it to the larger network of companies managed out of the Presidential Administrative Directorate.

Another source, an insider at Kyrgyz Railways, the national railway company, helped fill in the blanks of another case in which a state project had disappeared from public view.

In 2021, Kyrgyz Railways had announced that it was building a new railway tie factory to supply a rail expansion to connect Kyrgyzstan’s north and south.

The new facility would be state-owned, and would give the country “its own production base” for railroad ties for the first time, “to reduce dependence on the services of third party organizations,” Kyrgyz Railways said.

The railway insider suggested taking a closer look.

Early this year, in response to specific questions from journalists, Kyrgyzstan’s Ministry of Economy and Commerce confirmed that the factory was owned by Evro Shpal.

It would not comment on how it was financed or ended up in private hands. Kyrgyz Railways told journalists it had nothing to do with the facility, so couldn’t answer questions on it.

However, the source inside Kyrgyz Railways said the factory had indeed been paid for with state money before being handed over to Evro Shpal.

“The factory was to be built at the expense of the state,” he said. “It uses the iron of the state. After using everything, after building the plant, it goes to a private company.”

Four other companies that are building the new state projects follow similar patterns.

Two of them, like Evro Shpal, were incorporated by an obscure figure, then transferred to people with links to Tumanbayev and Japarov. Two others passed through the hands of many different shareholders, including several people linked to Tumanbayev.

There is no definitive evidence that Japarov has anything to do with the five companies, but the firms all have multiple connections to his family members and the head of his Presidential Administrative Directorate, raising serious questions about how he is allocating the contracts for major state projects — especially given Kyrgyzstan’s newfound lack of transparency.

And all five of them appear to be interlinked.

“How Much Does It Cost?”

Reporters relied heavily on open-source information, like social media posts, for this investigation since public information about state contracts has been cut off.

Bolot Temirov, the founder of media outlet Temirov Live and OCCRP’s partner on this investigation, said journalists were being forced to get more creative as repression increased and transparency plummeted in Kyrgyzstan.

“A huge layer of government procurement carried out by state-owned enterprises has been hidden from view, while there is massive persecution of journalists who do investigations, show information, make news, creating an atmosphere of fear,” he explained.

“Under such conditions, finding and confirming becomes quite difficult to do, and the role of sources, insiders, and so on becomes more important, as well as social networks and making direct requests to government agencies.

With the lack of officially sanctioned information on state projects, it’s not just journalists who are turning to social media for answers. Even members of parliament say they are confused by the situation. One prominent MP, Dastan Bekeshev, complained on Facebook in 2022 that he was unable to get answers from the government on who owned a company building schools in Bishkek.

“How much does it cost, or who do you need to be, for the Justice Ministry to hide or distort information about a company close to you?” Bekeshev asked in his post.

Even the workers building them don’t appear to know who is paying them. In one case, construction workers at Jyrgalan resort addressed a message to Japarov on TikTok.

“We poured the concrete of all the cottages, everything is finished. Those who worked after us have already received their money. We still can’t get our money,” a builder said in a video with his colleagues. “They continue to deceive us. What kind of firm this is… We can’t reach its management. [They owe] a total sum of about 5 million soms.”

As state contracts have become more opaque, occasional snippets of information still emerge, sometimes through government decrees and resolutions published on official websites. One such decree, posted online in August 2023, caused public outcry after it revealed that the company building the new Presidential Palace would receive three plots of land in the south of Bishkek. Experts consulted by Radio Azattyk estimated the land could be worth as much as $77 million.

“[We] still don’t know how much money was taken from the budget to begin the construction… [but] you might have a heart attack,” wrote the activist member of parliament, Bekeshev, on social media after the decree was revealed. “For your own health, information about the actual expenditure on the construction of the Presidential Palace is classified.”

The decree also helped publicly reveal the name of the company building the palace for the first time: It was Inshaat Stroy Building, the same one named in this investigation as part of the network being run out of the Presidential Administrative Directorate.

But finding out who actually stands behind Inshaat Stroy Building is another matter. Radio Azattyk managed to link it to figures close to Tumanbayev, but the story of how it was selected to build the project remains largely unexplained. “Why don’t they make public information about how much the construction costs and on what terms the agreement was concluded with Inshaat Stroy Building?” the journalists wrote.

Leila Seitbek, a prominent Kyrgyz human rights activist, said she saw a clear link between the attempt to withhold information on state spending and the government’s campaign against independent media outlets.

“They’re persecuting journalists precisely in order to prevent leaks of the very same kind of data that you’re now writing about,” she said.

“So that no one will write about it. So that no one will ever find out.”

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus