"From pig farm to Bitcoin mine: How Dagestan became Russia’s crypto Klondike"

In 2024, Russia stands as one of the world’s leaders in cryptocurrency mining, rivaling the United States.

While the government is trying to make Irkutsk the “mining” capital of Russia, crypto extraction has spontaneously become perhaps the most popular small business idea and investment area in Dagestan. The Insider’s correspondent traveled to the North Caucasian republic and explored the peculiarities of Dagestani crypto mining, which include electricity theft, law enforcement raids, and illegal enterprises working to the benefit of corrupt officials.

Crypto mining as a small business

The property is equipped with everything necessary for crypto mining — and for a comfortable life: motion sensors, the security guard’s cabin, an outhouse, a shed for equipment, a three-meter-tall fence, and cameras ringing the perimeter. We are on a farm in a village near the city of Kizilyurt. The land plots in the villages are at least a dozen meters apart, so the noise from generators and air conditioners does not disturb anyone, the owner says. We have to take his word at face value, because the farm is empty: all of the equipment was seized during the police raid. The owner of the property, Ibragim, has decided to sell the farm, which he equipped only three years ago.

At first, Ibragim mined cryptocurrency himself. Then he rented out the premises as a mining hotel — a room that houses someone else’s mining equipment for a monthly fee, plus around half of any profits generated. The last tenant got Ibragim into trouble by placing his equipment in a utility room, bypassing the meter. Russia’s federal electricity provider noticed the power theft immediately, but the owner says he only found out about the arrangement after it was too late:

“[The tenant] had dozens of different ASIC [application-specific integrated circuit] miners. We made all the necessary arrangements for legal crypto mining. We installed a one-megawatt transformer, paid for a 300-meter transmission line and Internet cable, and obtained all of the required permits. But he removed the meter and started stealing. The police seized ASIC miners worth tens of millions of rubles! And I’m afraid the law enforcement agencies might take an interest in me as well.”

A crypto mining farm in the suburbs of Kizilyurt

The electricity provider regularly raids cryptocurrency miners, whose activities are easy to detect due to their excessive electricity consumption. Dagestan ranks first in the North Caucasus in this metric, and it is most likely first in all of Russia when it comes to the number of detected electricity thefts used for Bitcoin mining.

Ibragim’s farm can accommodate nearly 200 Whatsminer 102-type mining machines. The utility room features two metal cabinets for holding them, along with large fans to keep the equipment cool. An ASIC miner of this sort consumes almost 3.4 kilowatts per day, and according to the farm owner, the cost of the appliance was typically recouped in around three months. With a Bitcoin price of about $35,000 and an electricity rate of ten cents per kilowatt-hour, one machine could bring in between $1,200 and $1,400 a month. Today, the conditions are even more favorable: electricity rates in Dagestan range from $0.03 to $0.05, and Bitcoin trades at approximately $62,000.

“To fill a single compartment in our utility room, I need 2.5 million rubles [~$27,350], as the compartment accommodates 24 devices at $1,100 each,” Ibragim explained. “As you can see, only very wealthy people can afford large-scale mining in Dagestan.”

But there are risks, even for wealthy entrepreneurs. Police raids on Dagestani crypto farms became more frequent in late 2023, and so miners are moving their equipment away from villages and cities into remote rural areas, but even there it has become difficult to connect to the power grid.

“The state is tightening the screws. Crypto mining in Dagestan has become highly problematic,” says Murad, who lives in Makhachkala. He mined cryptocurrency for two years but has decided to quit, fearing that the authorities could shut down his farm, seize the equipment, and impose a large fine. We met in a highland village an hour’s drive from Derbent, and to get here, I had to find an SUV. The dirt track leading to the village was potholed, and the morning rain had turned it into a swamp. All that’s left of Murad’s farm is a shipping container holding bunches of wires — not as advanced as Ibragim’s setup.

The inside of a shipping container converted into a crypto mining room, with shelves for ASIC miners on the left and fans on the right

“First we bought the container and the equipment and installed everything in Makhachkala,” Murad says. “Then we moved everything to the mountains. But our neighbors were unhappy about the mining and threatened to call the police. I’ve already sold the miners, and now I’m selling the containers.”

Cold ground is a miner’s friend

In early 2023, Russia ranked second in the world in cryptocurrency mining capacity — behind only the United States — and third in the number of coins mined. However, uncertainty around the American regulatory environment, plus the prevalence of lower mining costs in Russia, may soon be enough to effect a change at the top of the leaderboard, industry insiders say. Russia’s previous rivals in bitcoin mining, Kazakhstan and China, have dropped out of the top three precisely because of stricter domestic legislation.

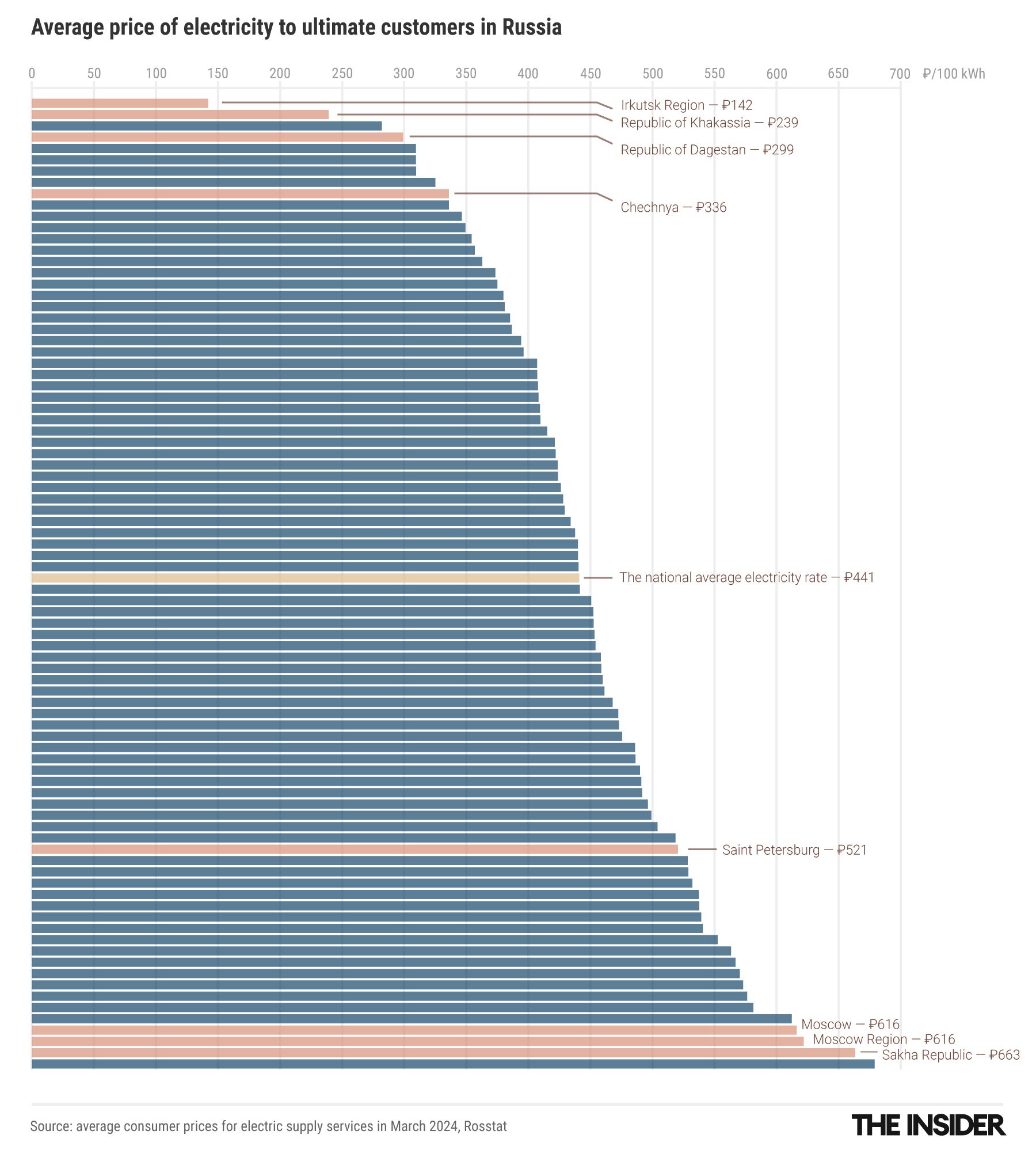

Mining cryptocurrency in Russia is profitable for several reasons. First, the practice is not yet seriously regulated. Second, the country has low electricity rates. Finally, the cold climate helps keep the equipment cool without the need for extra inputs. With the exception of the United States, the top cryptocurrency-producing countries have cheap energy or a cold climate — and most often both. For example, Canada and Iceland have electricity prices below the global average and well below typical European rates, while in Argentina electricity is much cheaper than in Russia and the cool weather in the south of the country lasts all year round.

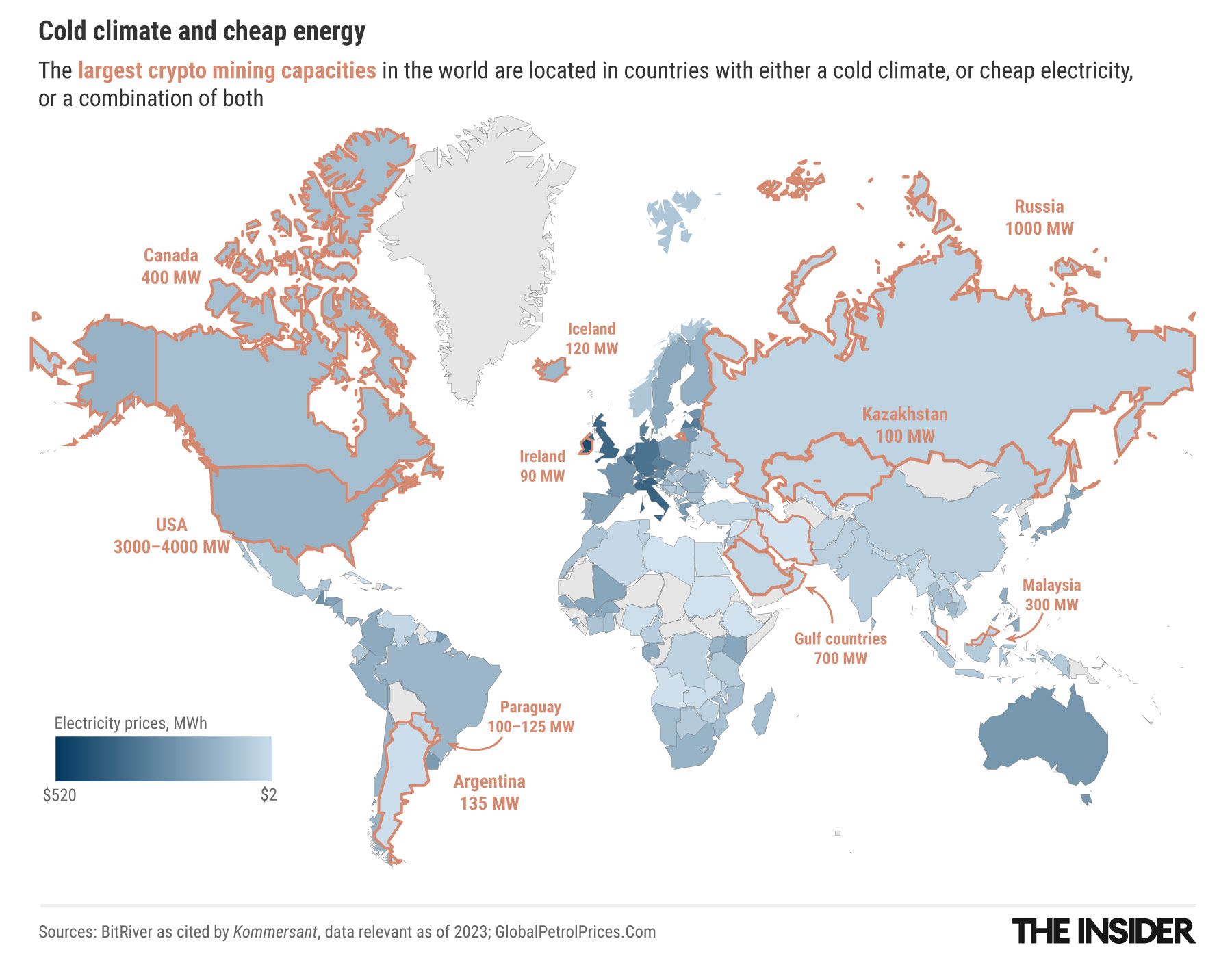

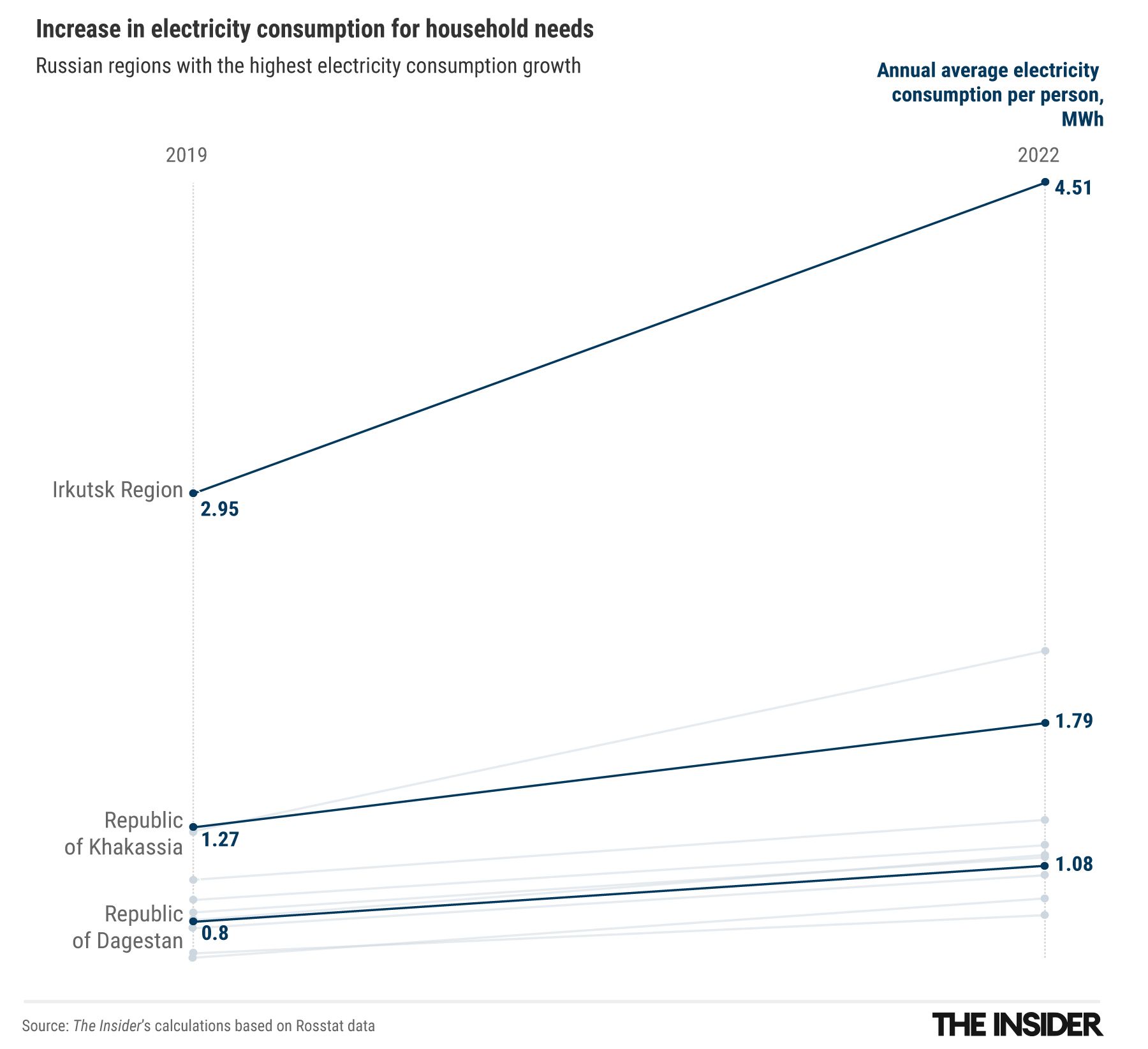

While crypto mining is practiced all over Russia, reports about the fight against illegal miners most often come from Siberia and the Caucasus. Electricity is very cheap there, especially given the preferential rates for rural areas. Over the past five years, the North Caucasus and Siberia saw a surge in electricity consumption, according to The Insider’s research.

Russian Minister of Energy Nikolai Shulginov reported that Russia’s miners consumed 1.5 gigawatts in 2023, and this figure is projected to increase to five or six gigawatts. However, BitRiver believes that these values only cover industrial mining. Private mining — that is, activities undertaken by individuals who purchase equipment and start mining cryptocurrency on their own — likely consumes a comparable amount of energy.

Energy theft: “You grab the kids and take them to grandma’s at 3 a.m. to keep them warm”

Since private miners use up large volumes of energy at regular tariffs, their activities meet resistance from both energy companies and locals.

Electricity providers are unhappy that they are missing out on profits by selling large volumes of energy at regular rates

Energy providers, which believe they are under-receiving profits, are trying to combat mining, and Dagestan has become the center of this confrontation in the Caucasus. In 2023, regional authorities discovered and shut down 16 illegal crypto farms, whose owners did not pay for electricity at all. The local electricity supplier, Rosseti North Caucasus, remains on the lookout for such facilities.

A transformer substation in Reduktorny near Makhachkala. Locals blame the frequent blackouts on dilapidated power systems and equipment — and on crypto miners

Locals, for their part, believe that the power cuts have become more frequent, and they blame this specifically on crypto mining farms. Musa, a young man from Novy Khushet, recalls how the police busted a large mining installation right next to his house:

“In Soviet times, it used to be a pig farm, with long buildings. There are no more pigs, as the farm fell into private hands and everything collapsed. The land changed hands several times. Once, I saw a wooden fence had been built around the premises. There were wires, some noise, people coming and going. I wondered if the owner of the land had finally shown up.”

But then the transformers started burning, and the lights would go out even late at night, when people hardly use household appliances and the load on the network should be lower. Winter was the worst, Musa recalls:

“Our house uses electric heating. That is, the heating goes off with every blackout, and I grab the kids right out of bed at two or three in the morning and take them either to my mom or to my mother-in-law. Our house cools down very quickly because the second floor is empty, and all the heat escapes quickly through the ceiling, so now I’m adding extra insulation.”

Musa and his neighbors complained to the police about the strong noise coming from the facility. In January, law enforcement officers accompanied by energy provider representatives searched the premises and discovered more than 70 ASIC miners, several powerful fans, and a power generator. The equipment was illegally connected to the city’s power grid. “They bought the equipment, found a derelict building, bypassed the meter, switched it on, and started having fun!” Musa complains.

“They plugged in the equipment, bypassing the meter, and started having fun!”

“Recently, another mining farm was discovered right outside the fence of a large electrical substation. Under the noses of the power companies! How was this possible? Are you saying no one had seen it? I’ll never believe it.”

Workers remove illegal wires supplying power to a mining farm in Novy Khushet

The authorities of Makhachkala’s Leninsky District posted a video of their raid on a farm near Musa’s house in Novy Khushet. According to the arrested landowner, the farm had operated for about a month, and the electricity provider representative in the video assessed the cost of stolen power at approximately $220,000. Previously, another mining farm was shut down in Novy Khushet in 2022 after stealing $12,000 worth of energy. In June 2020, a mining farm in the same district was busted after allegedly stealing electricity worth $372,600.

Authorities are so concerned about the impact of crypto mining on the power grid that during the frosty weather of January 2024, Rosseti North Caucasus asked mining farm owners to shut down their equipment so as not to overload the region’s infrastructure.

A similar situation exists in the Irkutsk Region, which is believed to mine around half of Russia’s Bitcoins. Here, many of the enterprises are legal, yet locals are convinced that power companies prioritize miner’s needs over those of the wider population. In December 2023, residents of the village of Khomutovo (30 kilometers from Irkutsk) recorded an appeal to Vladimir Putin, blaming cryptocurrency mining for the lack of heating in their homes:

“Three years ago, a new substation was built to ease the load on the grid and ensure that all our villages have enough power capacity. But the substation currently powers mining farms using electricity on an industrial scale. All nearby villages are freezing. There’s no power in the houses. Our government and local authorities are telling us that we should install generators and use stoves for heating.”

The regional electricity provider, Rosseti Siberia, also blames cryptocurrency mining for power grid accidents. “Electricity networks are designed for household loads, taking into account a surge factor (ranging from 10–20% of the declared capacity). Continuous high consumption impacts the quality of electricity, overloading network elements and causing their failure,” the company explained.

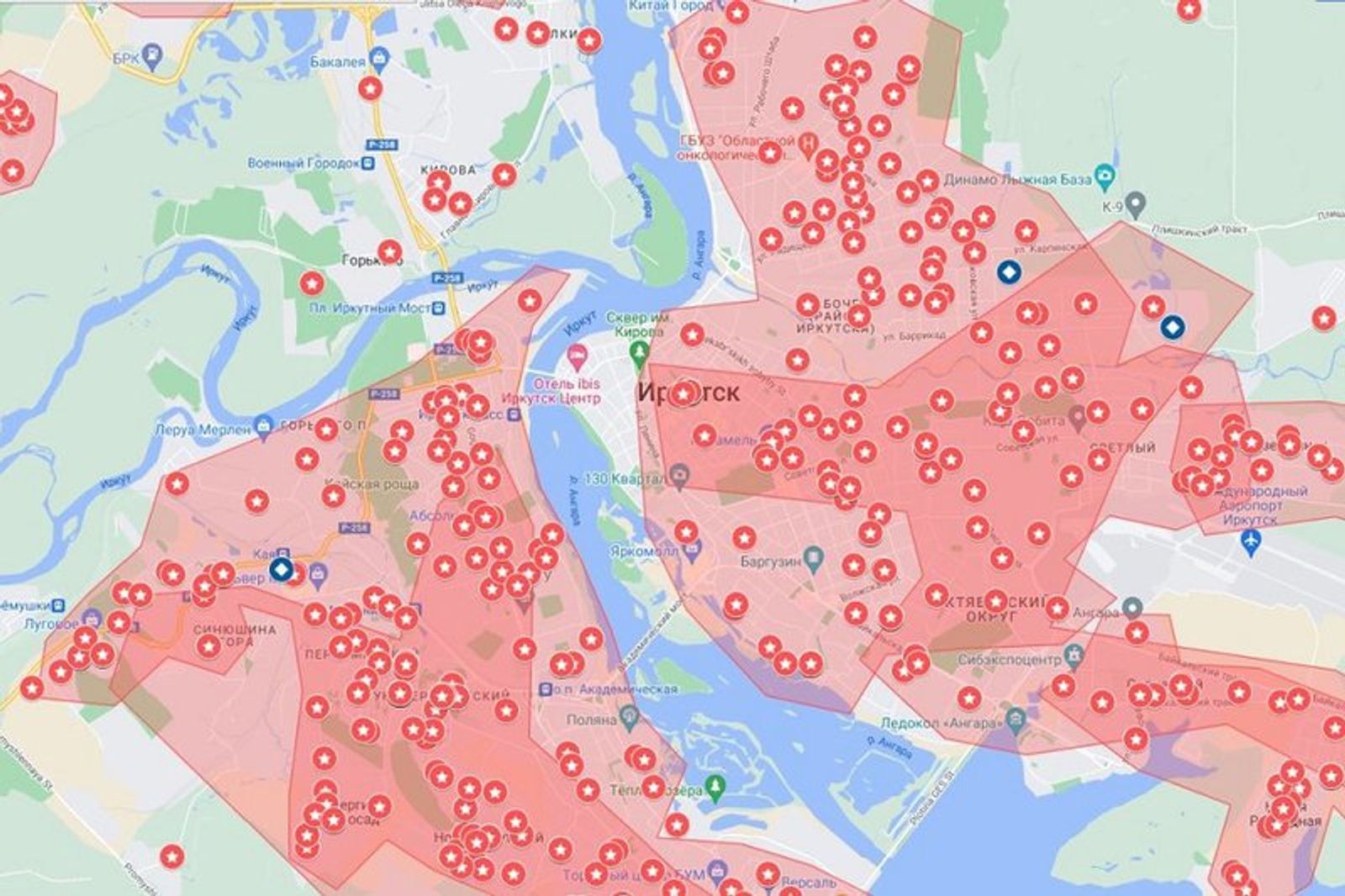

To combat miners, the local power company even created a map of detected “gray” farms by analyzing energy consumption data and surveying locals, who are disturbed by noise and vibration from the mining machines, in addition to the power outages.

A fragment of the Irkutsk Region “gray mining map” as of June 2023

IrkutskMedia / Irkutskenergosbyt

The state is also taking action against crypto miners in both Irkutsk Region and Dagestan. As a result, Dagestani pensioner Fatimat Seferbekova was detained in October 2020 in the city of Dagestanskie Ogni. She was charged with illegal mining after the police discovered a farm of 44 mining devices connected directly to the power grid in premises belonging to her. In late 2021, the court handed down a verdict: Seferbekova was found guilty of “causing property damage by deceit or abuse of trust on a large scale.” But she got off with a fine of $548, though even before the end of the trial, she had also repaid approximately $3,300 to the local electricity supplier.

Seferbekova is one of many Dagestanis who have taken up crypto mining in recent years — and one of the few brought to justice for illegally connecting to the power grid. In another example, Dagestan’s largest crypto farm was busted by the Federal Security Service in late January 2022. Operatives seized 4,343 miners worth about $5.5 million, sealing them in as many as 13 railcars.

Operative footage of the Federal Security Service for the Republic of Dagestan

“Officials are turning a blind eye to farms”

Makhachkala’s Reductorny district is frequently mentioned in the press in connection with the detection of mining farms. The area features several new high-rise apartment blocks, and control over the use of basements and underground parking lots is not exactly thorough, allowing creative tenants — and local officials — to use them for mining facilities.

It was here in late January 2024 that law enforcement agencies shut down an operation that consisted of 620 machines. The authorities also seized a laptop, a video recorder, and a data storage device. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the farm belonged to a 35-year-old local, whose name was not disclosed. It was set up in the underground parking garage of an apartment block on Nasrutdinov Avenue. The police reported that the owner had illegally connected the equipment to power lines, bypassing the meter. The farm consumed 1.75 million kWh of electricity worth more than $133,700 — enough to cover the needs of 120 apartments for three months.

A search of a crypto farm in Reduktorny, Makhachkala, January 2024

Budny Dagestana Telegram channel

“The situation with blackouts seemed to improve [around the time of the raid],” a resident of Reduktorny recalls. “It might have had to do with the raids on the miners.”

Locals interviewed by The Insider complain that authorities have been ignoring their reports of mining activities — this after encouraging them to call the corruption reporting hotline. “When we ask our precinct officer to check the garages we think may house a mining farm, he won’t even budge. I think these miners definitely have someone’s protection,” a local resident said. “Not to mention how expensive mining equipment is!”

As a source close to the Dagestani government admitted to The Insider: “There are many farms. Dagestani officials are aware of what is going on.” According to the source, an ordinary individual can install “no more than a couple of machines bypassing the meter,” but they won’t earn much. “Farms with dozens of appliances wired to bypass the meter all exist with the authorities’ permission, so to speak. Ordinary people can’t do that — they’ll be shut down immediately. It is necessary... how shall I put it…to interest the right people, in Rosseti, so that they turn a blind eye to your mining,” he says.

Dagestani bloggers and journalists are frustrated that the authorities are keeping a lid on the identities of the arrested crypto miners. “I asked right away: who owns this farm? It was obviously some middle-ranking official, because more powerful farms belong to officials of higher rank,” blogger Gasan Gadzhiev wrote. The farm he mentioned was discovered in the Kirovsky District of Makhachkala and housed 250 machines using 3.5 kVA each. “The farm’s activities caused significant congestion on the grid, resulting in the loss of 70% of electricity and affecting almost 1,500 residents and 10 commercial facilities,” the Dagestani Interior Ministry stated for the press.

Similarly, there is no public information about the owners of the farm network that was shut down in January 2022, nor of the large farm in Karaman, which had consumed 546,500 kilowatt-hours worth more than $13,000 over the several months preceding the raid in early February. Karaman receives the largest number of consumer complaints about voltage drops and power supply interruptions in all of the Makhachkala area.

Another crypto mining farm illegally consuming electricity was found in Khasavyurt during the search and arrest of Major Ilyas Khazbulatov, who served in the regional economic crime and anti-corruption unit of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Notably, it was not the farm that got him arrested, but his extortion of $220,000 from the owner of a fur and leather business.

Power grid issues: are miners to blame?

Large crypto farms can indeed wreak havoc on the power grid. However, Dagestan and Irkutsk Region struggled with the deterioration of their power grids and transformers even before the Bitcoin mining boom. According to Ali, the owner of a crypto mining hotel in Dagestan, miners often upgrade transformers so that the overloads do not cause problems for the locals — or result in downtime for the mining machines.

“There are unscrupulous miners, of course, who overload transformers and create problems for ordinary tenants. I don’t think it’s right,” Ali says. According to him, mining hotels prefer to operate legally, but most cooperate only with businessmen who buy a lot of machines.

“We don’t install fewer than ten pieces. No airheads and blabbermouths allowed — only serious people,” the owner of a mining hotel in Makhachkala wrote in a classified ad. Like his peers, the owner takes half of the cryptocurrency mined.

Hotel owners use the revenue to pay for the electricity, and they assume responsibility for the machines installed on their premises. “An average customer brings in 100 machines. The enterprise is perfectly legal. It’s a source of extra income,” hotel owner Idris explains. He believes that the raids, which started in late 2021, have motivated more mining farms and hotels to connect to the grid legally.

In Makhachkala’s Reduktorny and Primorsky districts, locals regularly ask the police to check underground parking lots, garages, and construction trailers for illegal mining farms

Several mining entrepreneurs interviewed by The Insider believe that officials are deliberately making scapegoats out of them, spreading rumors that widespread power outages are related to cryptocurrency activities. Murad, an entrepreneur who had to sell his crypto-mining farm in a mountain village near Derbent due to complaints from neighbors, is one of them.

“A small farm won’t hurt much, especially through the meter, and the average person doesn’t have money for a big one,” Murad explained. “Instead, [the authorities] should take a closer look at the officials who run the big farms. Whenever someone puts two ASIC miners on their balcony, the police come running — but they turn a blind eye to the officials’ farms with dozens of machines.”

“Whenever someone puts two ASIC miners on their balcony, the police come running — but they turn a blind eye to the officials’ farms with dozens of machines”

“There will be no comment. Leave before we call the police!”

ln the summer and fall of 2023, locals in Makhachkala blocked traffic near a trolleybus depot in Kirovsky district several times in order to protest days-long power cuts in the Dachny, Vagonnik, and Novy Poselok district. In January, a major crypto mining farm was discovered here, right in the garages, but neither the exact number of units nor the timeline of its operation was reported.

The trolleybus depot in Makhachkala where a mining farm was set up

“No, we did not see anything. Yes, we’re blind,” a depot employee replies sarcastically, and immediately phones the management.

Since the closure, there have been hardly any blackouts in the neighborhood, but locals cannot say for sure whether this is linked to the mining farm shutdown. Still, they find energy theft accusations highly credible.

“The state enterprise has unlimited access to free electricity. Do you really think they didn’t use it?” the tenant of a nearby high-rise apartment building answers our question with a question. These apartment blocks, located around 100 meters from the trolley depot, regularly suffered hours-long power outages. “From nine to six, we had no power, which means no hot water and no elevators. And no one cut our rates!”

This is not the only case of crypto mining equipment detected on the territory of state enterprises. In Kizlyar, state-owned electrotechnical company Elektron set up a farm with 3,000 machines. In the village of Novoye Gadari near Kizilyurt, an agricultural cooperative used energy purchased at a preferential tariff to mine cryptocurrency.

Right now, there is no equipment in the trolley garages — at least not in the ones open for public access. After a couple of minutes, a security guard comes up and asks us to leave the premises: «Management says no comment. Leave before we call the police.”

Inelastic demand

Despite more frequent raids, mining farms are springing up throughout Dagestan like mushrooms after rain. Musa, who lives near the old pig farm in Novy Khushet, says that many people who can afford to buy at least a few ASIC miners are trying to master the craft:

“I went to my uncle’s house in a highland village at the border with Azerbaijan. A family like any other. They live on the second floor of the house, using the first for gas cylinders and all sorts of stuff — like a shed. This time, when I went down to the first floor, I saw mining equipment there! He says to me, ‘Look, we have a mining farm now. It brings us money. I didn’t understand at the time: ‘What do you mean brings money? It’s just sitting there.’ As it turns out, a friend of his put his equipment in their shed and shares some of his profits.”

Musa’s relatives have officially connected the equipment through a meter. They are not stealing energy, meaning the profit margin is not very good. Still, his brother has also considered taking up mining. “For now, he lives in an apartment and works at a service center fixing ASIC miners. He says that if you live in a private house, paying $50-70 worth of bills, and install a couple of miners, they can cover these expenses for you.”

If you don’t steal energy, the profit margin is not very good

A mining hotel owner interviewed by The Insider believes that almost four out of ten households in Makhachkala have at least one mining device. The compact Whatsminer M30S+ — one of the most popular in Dagestan — can be placed in an apartment, and sellers of mining equipment enjoy steady demand for their goods: “Yesterday we received 15 Whatsminer 102 Th/s ASIC miners and immediately sold all of them to a single buyer. He was unhappy that we didn’t have more because he wanted to buy 25 pieces,” a sales assistant at a mining equipment store in Makhachkala said. According to him, Whatsminer 102 Th/s is the most in-demand model in Dagestan because of its price-to-performance ratio. “Earlier they sold at $1,020, but now we’ve upped the price to $1,100 — and that’s for bulk orders. They are not easy to come by in Dagestan. I don’t think there are any more left in Makhachkala.”

“Everyone who wants extra income buys mining equipment, regardless of gender or age. People at least have extra money to improve the lives of their near and dear,” the mining equipment firm representative said, although other sellers claim that mining is an industry for the young.

It was a group of young strangers who allegedly talked Fatimat, the pensioner convicted for energy theft, into buying the miners. As she told the court, “some young guys she didn’t know” came to her and proposed that she buy a mining farm as a source of income. She agreed because she had an empty room. The guys said they would install and connect everything themselves. She suggested they pull a cable “from a neighboring pole to the equipment directly.”

Fatimat says she planned to connect them to the meter after a couple of months, but the police arrested her before she got around to it. The local electricity suppliers found out that the pensioner had set up a mining farm in the back room when all the neighbors began to lose electricity: “All networks began to fail. The transformer was boiling, and consumers experienced frequent voltage drops. We started getting calls about the failure of electrical appliances, with people demanding compensation for the damage caused.”

Steps towards regulation

In mid-2023, Russia’s Ministry of Finance estimated miners’ profits at $4 billion per year. Sergei Bezdelov, director of the Industrial Mining Association, believes that the annual tax potential of Russia’s cryptocurrency industry is estimated at approximately $550 million. Ever since industrial and private mining experienced rapid growth in Dagestan, Irkutsk Oblast, Khakassia, and neighboring regions, the authorities and energy companies have been hoping to regulate the practice. Both regional and federal energy officials and lawmakers are advocating for bills that would establish a special electricity rate for miners, and energy provider Rosseti agrees that electricity should be more expensive for major consumers:

“So far, the only method of legalizing mining farms and reducing the excessive load on the grid is to introduce a differentiated tariff for electricity: the more you consume, the more expensive each kilowatt-hour. A differentiated rate puts energy consumption in order, contributing to a more reliable electricity supply in the region.”

The authorities loathe the fact that crypto mining is not regulated as an economic activity, meaning that it brings no taxes to the budget. Russia is yet to adopt a law on cryptocurrency mining — this despite the fact that a draft bill has been under consideration for a year and a half. Anatoly Aksakov, head of the State Duma’s Financial Market Committee, hinted that the progress of the bill was being hindered by some critics under the pretext that it could be used to withdraw capital from Russia. However, in late April 2024, the committee presented the latest version of a proposal to add crypto mining to the digital currency law. The latest version of the bill, published on the parliament’s website, retains an explicit ban on any offering of digital currencies and services related to their issuance to the general public:

“A ban [is established] on advertising (or) any other form of offering to the general public of digital currencies, as well as goods (works, services) with the purposes of organizing the issuance, issuance, organization of circulation, or circulation of digital currency (except for the mining of digital currency),” the committee stated in the conclusion.

The bill provides for other restrictions on crypto mining in Russia. At the same time, one of its authors, MP Andrei Lugovoy, seems to have a personal interest in getting the bill adopted. In 2022, the Dossier Center revealed in an investigation that the deputy’s wife, Ksenia Lugovaya, owns a stake in a company supplying electricity to industrial consumers in Irkutsk Region and a cryptocurrency exchange at the Moscow International Business Center. Their findings were confirmed when Lugovoy’s mailbox was hacked by Ukrainian hacktivists InformNapalm.

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus