The $2bn dirty-money case that rocked Singapore

A Singaporean court has begun handing out sentences in a sensational case, which saw 10 Chinese nationals charged for laundering $2.2bn (£1.8bn) earned from criminal activities abroad.

The scandal embroiled multiple banks, property agents, precious metal traders and a top golf club. It led to extensive raids in some of the most affluent neighbourhoods, where police seized billions in cash and assets. The lurid details have gripped Singaporeans - among the seized assets were 152 properties, 62 vehicles, shelves of luxury bags and watches, hundreds of pieces of jewellery and thousands of bottles of alcohol.

Earlier this month, Su Wenqiang and Su Haijin, became the first to be jailed in the case. Su Haijin, police said, jumped off the second-floor balcony of a house trying to flee arrest. Both men will serve a little over a year in prison, after which they will be deported and barred from returning to Singapore. Eight others are still awaiting the court’s decision.

Even as it draws to a close, the case - the biggest of its kind in Singapore - has raised inevitable questions. The money that paid for their plush lives in the country, prosecutors said, came from illegal sources overseas, such as scams and online gambling.

How did these men, some of whom had multiple passports from Cambodia, Vanuatu, Cyprus and Dominica, live and bank in Singapore for years without drawing scrutiny? It has sparked a review of policies, with banks tightening rules, especially around clients who hold multiple passports.

Most important, the case has spotlighted the country’s struggle with welcoming the super wealthy, without also becoming a destination for ill-gotten gains.

Show me the money

Singapore, which is often referred to as the Switzerland of Asia, started wooing banks and wealth managers in the 1990s. Economic reforms in China and India had begun to pay off, and then in the 2000s, a newly-stable Indonesia saw wealth grow as well. Soon, Singapore became a haven for foreign businesses, with investor-friendly laws, tax exemptions and other incentives.

Today, the ultra-rich can fly into Singapore’s private jet terminal, live it up in luxurious quayside neighbourhoods, and speculate on the world’s first diamond trading exchange. Just outside the airport is a maximum-security vault called Le Freeport that provides tax-free storage for fine art, jewels, wine and other valuables. The $100m-facility is often dubbed Asia’s Fort Knox.

Singapore’s asset managers drew S$435bn from abroad in 2022, almost double the figure in 2017, according to the country’s market regulator. More than half of Asia’s family offices - firms which manage private wealth - are now in Singapore, according to a report by consulting giant KPMG and family office consultancy Agreus.

They include those of Google co-founder Sergey Brin, British billionaire James Dyson and Chinese-Singaporean Shu Ping, boss of the world’s biggest chain of hotpot restaurants, Haidilao.

Authorities say some of the accused in the money laundering case may be linked to family offices that were given tax incentives.

"There is an inherent contradiction for a place like Singapore, which prides itself on clean and good governance but also wants to accommodate the management of massive wealth by offering advantages such as low taxes and banking secrecy," says Chong Ja-Ian, a non-resident scholar at Carnegie China.

"The risk of also becoming a banker for individuals who earned their money through nefarious or illicit means grows."

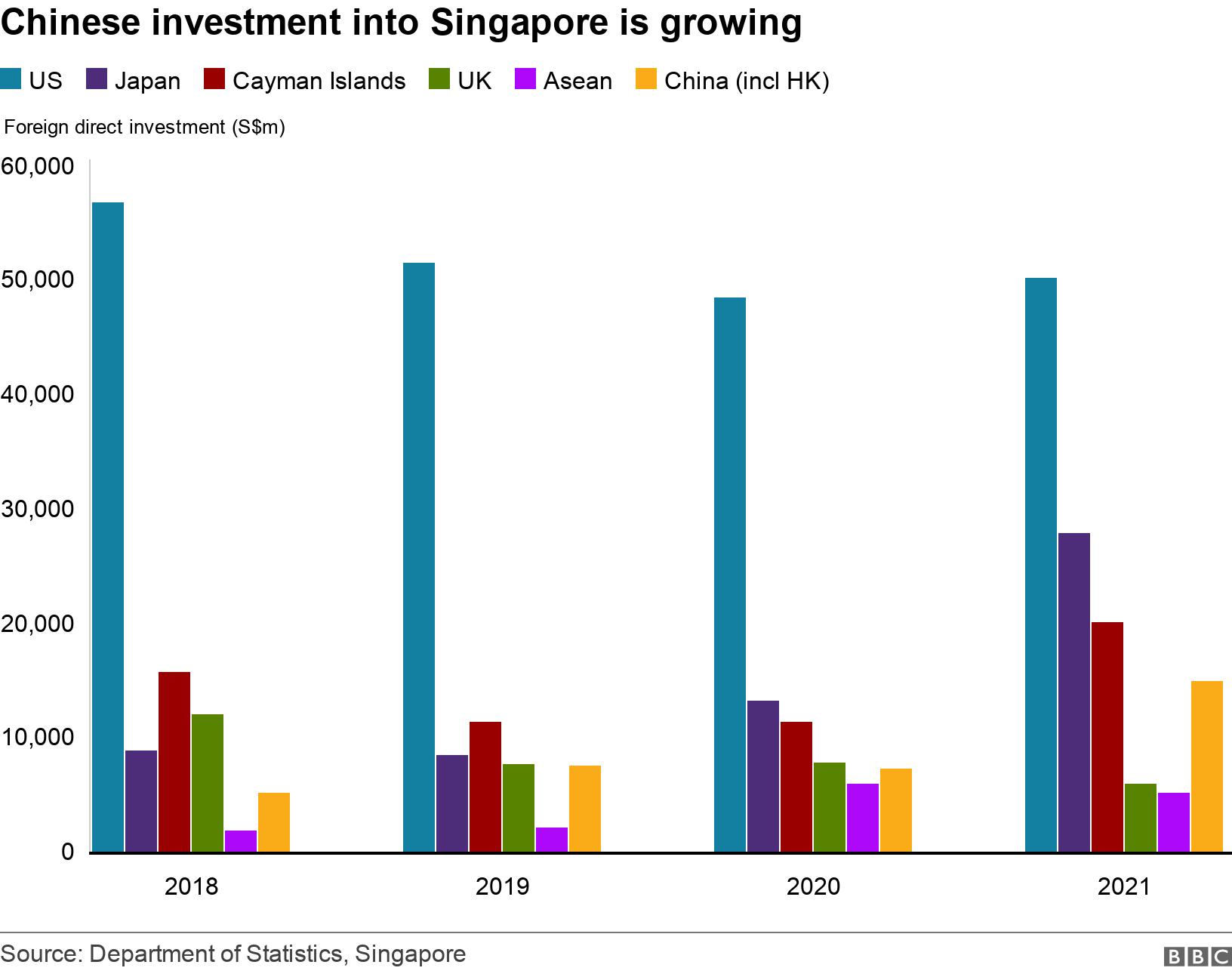

For rich Chinese, Singapore is a top choice because of its reputed governance and stability, as well as its cultural links to China. And more Chinese money has been entering Singapore in recent years.

One of the 10 suspects in this case was wanted in China since 2017 for his alleged role in illegal gambling online. Prosecutors claimed that he settled in Singapore because he "wanted a safe place to hide from the Chinese authorities".

Hiding in plain sight

This isn’t the first time Singapore-based banks have been implicated in a financial crime. They were found to have played a role in cross-border laundering in the 1MDB scandal, where billions were misappropriated from Malaysia’s state investment fund. Dan Tan, who was once described by Interpol as "the leader of the world’s most notorious match-fixing syndicate" also had strong business links to Singapore. He was arrested here in 2013.

The country has strict rules targeting white collar crimes and is an active member of the Financial Action Task Force, a global body which targets money laundering and financing for terror networks. Over the years, banks have invested heavily to strengthen compliance, to screen prospective customers and to urge regulators to report suspicious transactions. But none of this is foolproof.

For one, it is difficult for regulators to spot suspicious cases in a sea of high-value transactions.

"It’s not just one needle in a haystack, but one needle in several haystacks," Singapore’s second minister for home affairs, Josephine Teo, told parliament in October last year.

Singapore’s buoyant property market is a popular means to "clean" dirty money, some experts pointed out. And there are the casinos, nightclubs and luxury stores.

"Massive amounts of money pass through Singapore’s banking system every day. Criminals can exploit this feature and disguise their money laundering activities among legitimate ones," accounting professor Kelvin Law from Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University told the BBC.

Singapore also does not limit the amount of cash that can be carried in and out of the country, only requiring a declaration if the sum exceeds S$20,000. And that is an advantage, says Christopher Leahy, the founder of Singapore-based investigative research and risk advisory firm Blackpeak.

"If you want to move lots of money, you hide it in plain sight and Singapore is a great place for that. There is no point putting it in the Cayman Islands or the British Virgin Islands, where there is nothing [to spend money on]," he said.

When asked for a response to analysts’ comments that Singapore’s advantages as a financial capital are also a draw for dirty money, authorities pointed the BBC to the law and home affairs minister interview in a local newspaper last year.

"We can’t close the window, because if we did that, then legitimate funds will also not be able to come. And legitimate business also can’t be done, or becomes very difficult to do. So we have to be sensible," K Shanmugam said.

"When you are successful, you are a major financial centre, a lot of money comes in, some ’flies’ will also come in," he added, referring to an oft-repeated quote of the late Chinese leader, Deng Xiaoping.

Singapore has to decide how far it will go in accepting "money with varying shades of grey", says Dr Chong of Carnegie China.

While increased regulation will help, he says transparency poses a bigger challenge: "Transparency goes against the very model of discretion that allows many wealth management hubs to thrive."

Some analysts say this may well be the price Singapore is willing to pay to retain its position as a financial hub.

"The vast majority of the funds are legitimate, after all," Mr Leahy says. "But there is an inevitable cost to being a major financial centre."

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus