How fentanyl producers in Mexico are adjusting to a challenging market

When Mario heard the news in mid-May 2023, he immediately suspended his operations.

This is reported by InSight Crime.

After five years of booming fentanyl trafficking in the northwestern state of Sinaloa, “the bosses,” as he called the Sinaloa Cartel faction of the Chapitos, issued a blunt directive: stop all production in the state.

Sinaloa had long been the epicenter in Mexico of illicit fentanyl production, a synthetic opioid linked to hundreds of thousands of overdoses across North America over the past decade. According to US authorities, the Chapitos – the sons of the infamous drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán – were among the key figures driving this epidemic.

“They told us, ‘Burn everything, the business is over,’” Mario recounted to InSight Crime at a seafood restaurant in Culiacán, the state capital, in September 2023. Since then, he has been out of work.

Mario is like most fentanyl producers InSight Crime has met over the last couple of years. He considers himself “100% independent” from any criminal organization. Although he operated within the Chapitos-controlled territory for years, he did not depend on them for his activities nor report to them. He sourced the materials, managed the chemical processes, hired security, and found clients himself. By his estimation, there were dozens of producers like him in Culiacán.

But his independence had limits. When the Chapitos gave an order, compliance was the only option. Defiance meant death.

“We all had to stop,” Mario said. Seven other independent fentanyl producers interviewed by InSight Crime in Culiacán between September 2023 and August 2024 echoed his account.

Though the reasons behind the prohibition were not entirely clear to the producers, many agreed that it came at a time of crisis for the fentanyl market. Prices had plummeted, authorities were ramping up efforts to disrupt the supply chain, and China – the main source of precursor chemicals – had tightened restrictions on some of the key substances used in production.

For producers like Mario, abandoning the business seemed like the wisest choice.

“Right now, it’s not worth it. Things are way too complicated,” said another producer interviewed in March 2024.

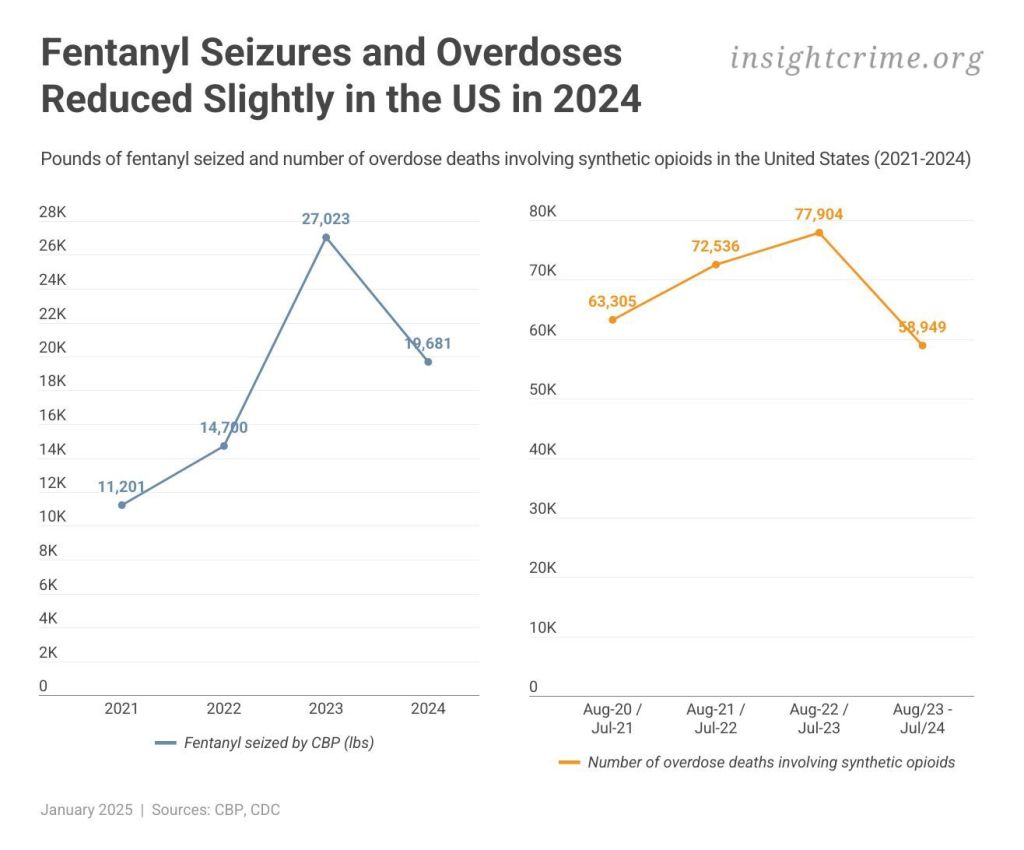

Notwithstanding the recent rise in seizures in Mexico, official data suggested that supply slowed following the ban. US Customs and Border Protection (CBP), for example, seized 21,889 pounds of fentanyl during fiscal year 2024 (approximately 9,928 kilograms), down from 27,023 pounds (12,257 kilograms) in fiscal year 2023. Meanwhile, the Mexican army reported the seizure of 1,500 kilograms of powder and 11.6 million pills in 2023. As of July 2024 they had only seized 160 kilograms and 1.3 million pills.

And for the first time in more than a decade, fentanyl overdose deaths in the United States fell, decreasing by roughly 17% in 2024 compared to the previous year.

Some attributed these changes to prevention and harm reduction efforts. Others, like the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), credited operations targeting cartels.

“The cartels have reduced the amount of fentanyl they put into pills because of the pressure we are putting on them,” said former DEA Administrator Anne Milgram in November 2024.

However, findings from our investigation add further complexities. After three years of tracking the synthetic drug supply chain in Mexico – including fieldwork in Sinaloa, Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Jalisco, Colima, and Michoacán, as well as interviews with close to a dozen producers and other key players in Mexico and China – we found that while fentanyl flows may have temporarily slowed and producers like Mario were forced to stop, the market is unlikely to be declining.

On the contrary, it may be maturing. Fentanyl producers appear to be adapting to challenges, in line with the global trend of constant evolution in synthetic drug markets.

Below, we explain four ways this adaptation is unfolding.

Centralizing Control in Sinaloa

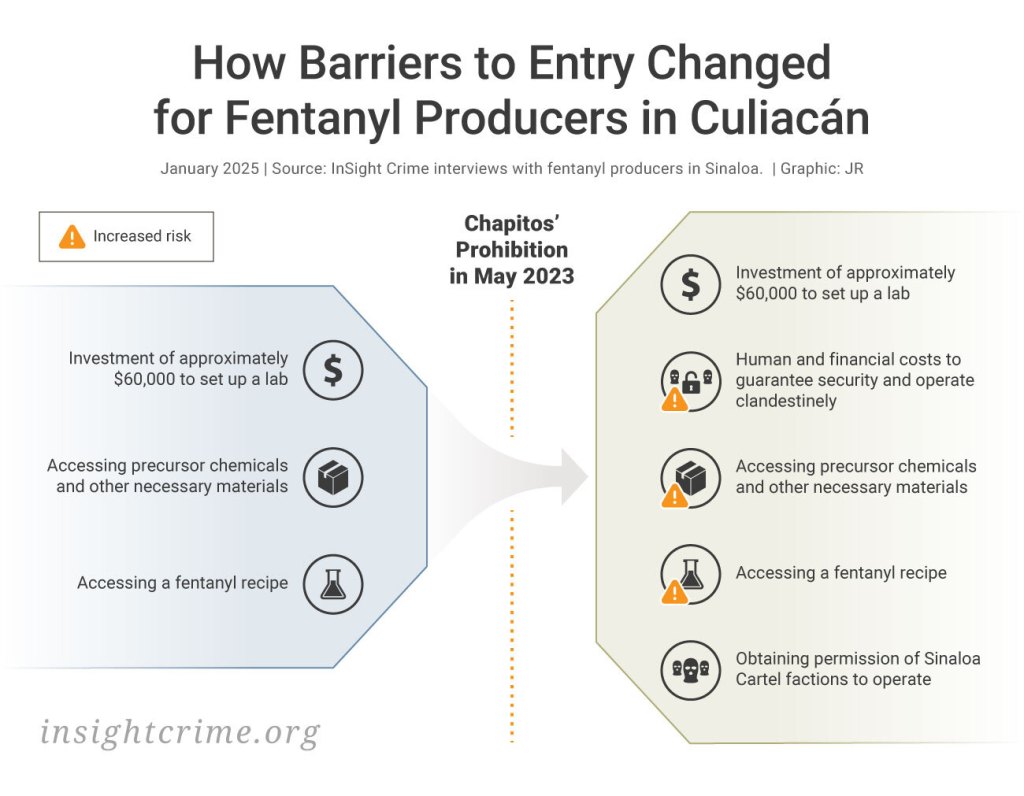

The first strategy comes from the Chapitos and other factions of the Sinaloa Cartel. While their prohibition did not entirely stop production in the state, it significantly raised the barriers to entry.

Before the prohibition, independent producers interviewed by InSight Crime in Culiacán described setting up a fentanyl production operation as a relatively simple process.

First, the necessary chemical precursors and other materials were readily accessible. In Culiacán, for example, networks of brokers specialized in connecting producers with suppliers of these substances in China and other countries, or collected the substances themselves and then distributed them, mostly within the city.

“You can get the materials on every corner here,” said Mario.

Second, learning to produce fentanyl required little more than access to a recipe, with no need for advanced knowledge of chemistry. These recipes could be purchased directly from suppliers in China or taught by amateur chemists. The know-how would then spread among production cells. Mario, for example, learned to cook fentanyl while working as an assistant in another lab. Another independent producer we interviewed said he paid for an “express course” offered by a foreign chemist in Culiacán.

The initial investment was also manageable. Independent producers reported spending around $60,000 to set up their labs. Two even claimed to have received funding from independent criminal “investors.”

These low barriers to entry allowed fentanyl production to flourish in Culiacán, according to the sources. And there was no shortage of “buyers” – a typical moniker referring to large criminal organizations operating along the border that transport the finished product.

In some important ways, the model was a victim of its own success. Fierce competition among producers drove prices down by nearly half. Several producers claimed that the wholesale price for a kilogram of pure fentanyl dropped from around $7,000 in Mexico and $15,000 at the border in 2022, to about $3,000 and $7,000, respectively, in 2023.

There were also significant variations in the purity of the final products. In 2022, for example, DEA analyses of fentanyl seizures revealed purity levels ranged from 0.07% to 81.5%. This inconsistency meant users could never predict which dose might be lethal, contributing to the unprecedented overdose rates in the United States. Inevitably, the increased scrutiny from authorities across the supply chain – and the attention attracted by the multiple actors involved in the process – proved bad for business.

The Chapitos’ ban changed the rules of the game. To continue operating, producers in Sinaloa needed more than access to materials and know-how, they also required permission, not just from the Chapitos, but also from other major factions of the Sinaloa Cartel. These included the Mayiza, a faction run by Ismael “Mayito Flaco” Zambada Sicairos; and another group run by Aureliano “El Guano” Guzmán, El Chapo’s brother.

In addition, producers had to invest significantly more in resources, both human and financial, to operate clandestinely – an option few could afford.

“Before, anyone could get the recipe … But now there are rules, and not everyone dares to take the risk,” said a fentanyl producer currently imprisoned in the Aguaruto Penitentiary near Culiacán during a phone call with InSight Crime in August 2024.

Gaining permission from Sinaloa Cartel factions is not straightforward and relies heavily on trust, according to several actors involved in drug trafficking that we interviewed in Culiacán.

An individual experienced in methamphetamine and fentanyl production, who claimed close ties to the Mayiza, explained that trust is gained by having family or other personal connections in the organization that can serve as references and collateral. Producers must also prove they can maintain a low profile.

Even then, building such a relationship could take years.

“Getting the ingredients is easy. Permission is the hardest part,” the producer noted from his home in a rural community an hour from downtown Culiacán.

It is unclear how many producers currently have permission to manufacture fentanyl in Culiacán, but sources said the number is likely small, with operations confined to remote areas such as Sinaloa’s mountainous regions to the east of the city.

“It’s a very selective group. They’re being more cautious,” said a coordinator of multiple synthetic drug labs who claims to have worked for various Sinaloa Cartel factions.

The effects of this tighter control over fentanyl production may be beginning to show.

For example, during our fieldwork, we found that with each visit to Culiacán, accessing sources with knowledge of the fentanyl trade became increasingly difficult. Even individuals we had interviewed multiple times, such as the lab coordinator, heightened their security measures, agreeing to shorter meetings or opting for phone calls through trusted intermediaries.

Additionally, the concentration of production in fewer hands appears to have affected fentanyl prices in Sinaloa. In August 2024, both the lab coordinator and another producer reported that the wholesale price for a kilogram of fentanyl in Culiacán had risen from $3,000 to $6,000.

Purity levels may also be stabilizing. According to the DEA’s latest analyses, five out of ten seized pills contained a lethal dose in 2024, compared to seven out of ten in 2023. While this cannot be necessarily attributed to the Chapitos’ prohibition, it suggests greater consistency in production methods.

It is unclear whether Mexican authorities see these dynamics in the same way. InSight Crime sent multiple interview requests to the Ministry of Defense (Secretaría de Defensa Nacional – SEDENA), the National Guard (Guardia Nacional), the Navy (Secretaría de Marina – SEMAR), and the Attorney General’s Office (Fiscalía General de la República – FGR) for their perspectives on the evolution of fentanyl trafficking in the country. We either received no response or had our requests denied.

What’s more, in public statements, the federal government largely maintains its longstanding denial of fentanyl production, a stance that has persisted since the administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador. And despite numerous international media reports, including InSight Crime’s own reporting, that illustrated local production, in February and July 2024, SEDENA commanders told local media they had not identified laboratories producing this opioid in Sinaloa.

However, local law enforcement officials in Baja California – who spoke anonymously due to lack of authorization to discuss the issue publicly – and Jesús Moctezuma Sánchez, the municipal police coordinator in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, stated that they continued to trace most fentanyl seizures at the border back to criminal networks in Sinaloa.

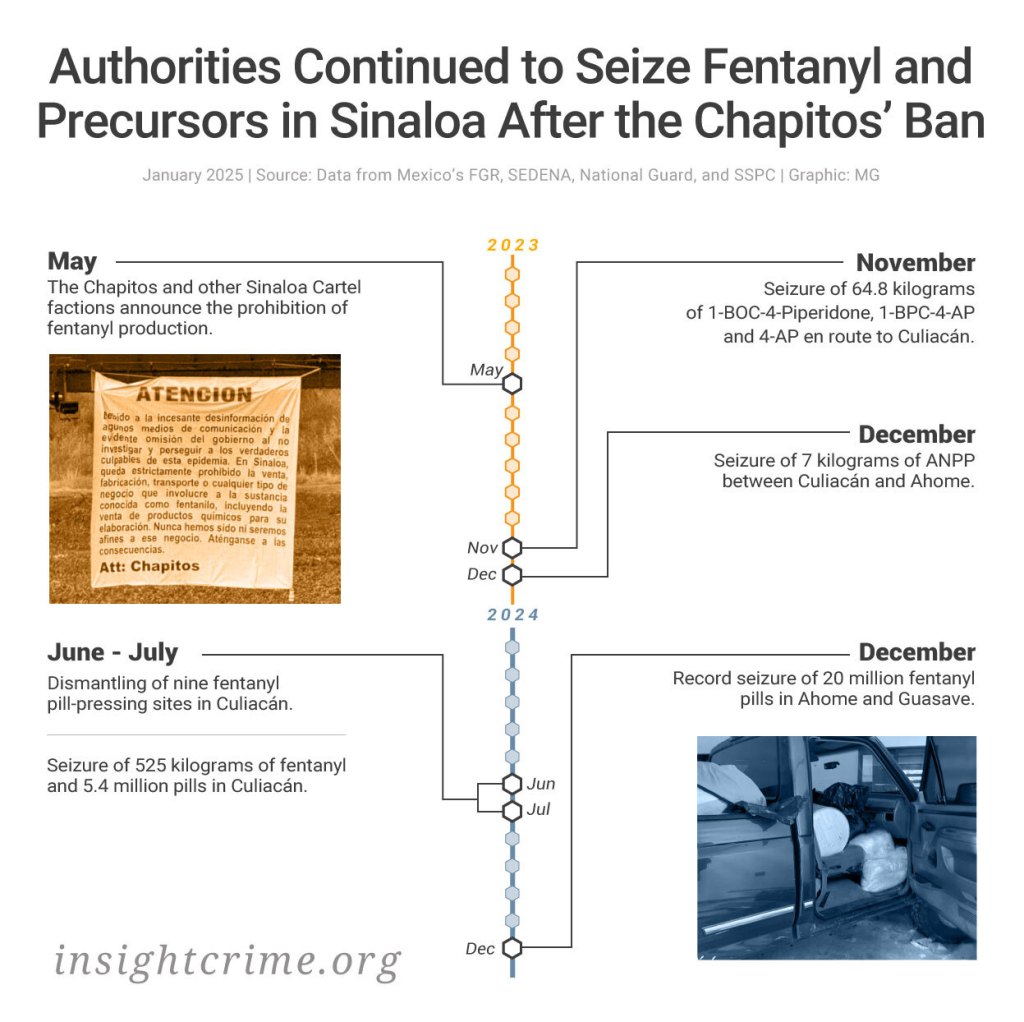

Seizure statistics from federal authorities further support this view. While there are no official statistics on fentanyl labs, the FGR continued reporting fentanyl precursor seizures in Culiacán and its surrounding areas after the Chapitos prohibition in May 2023.

For example, in November 2023, FGR reported seizing 64.8 kilograms of 1-Boc-4-Piperidone, 1-BOC-4-AP, and 4-AP –key fentanyl pre-precursors– on a passenger bus bound for Culiacán. A month later, authorities intercepted 7 kilograms of 4-anilino-N-phenethylpiperidine (ANPP), the primary fentanyl precursor, on the highway connecting Culiacán to Ahome, a municipality to the north of Culiacán.

Moreover, from June 2023 to July 2024, authorities dismantled nine pill manufacturing centers in Culiacán, while SEDENA and the National Guard reported confiscating at least 525 kilograms of fentanyl and 5.4 million pills in the city.

And in December 2024, the trend reached a new height with the seizure of 20 million pills in the neighboring municipalities of Ahome and Guasave, the largest fentanyl bust in Mexico’s history. Adrián Cebreros Pereyra, an alleged fentanyl cook linked to a Sinaloa Cartel faction, was arrested in the operation.

Migrating Production

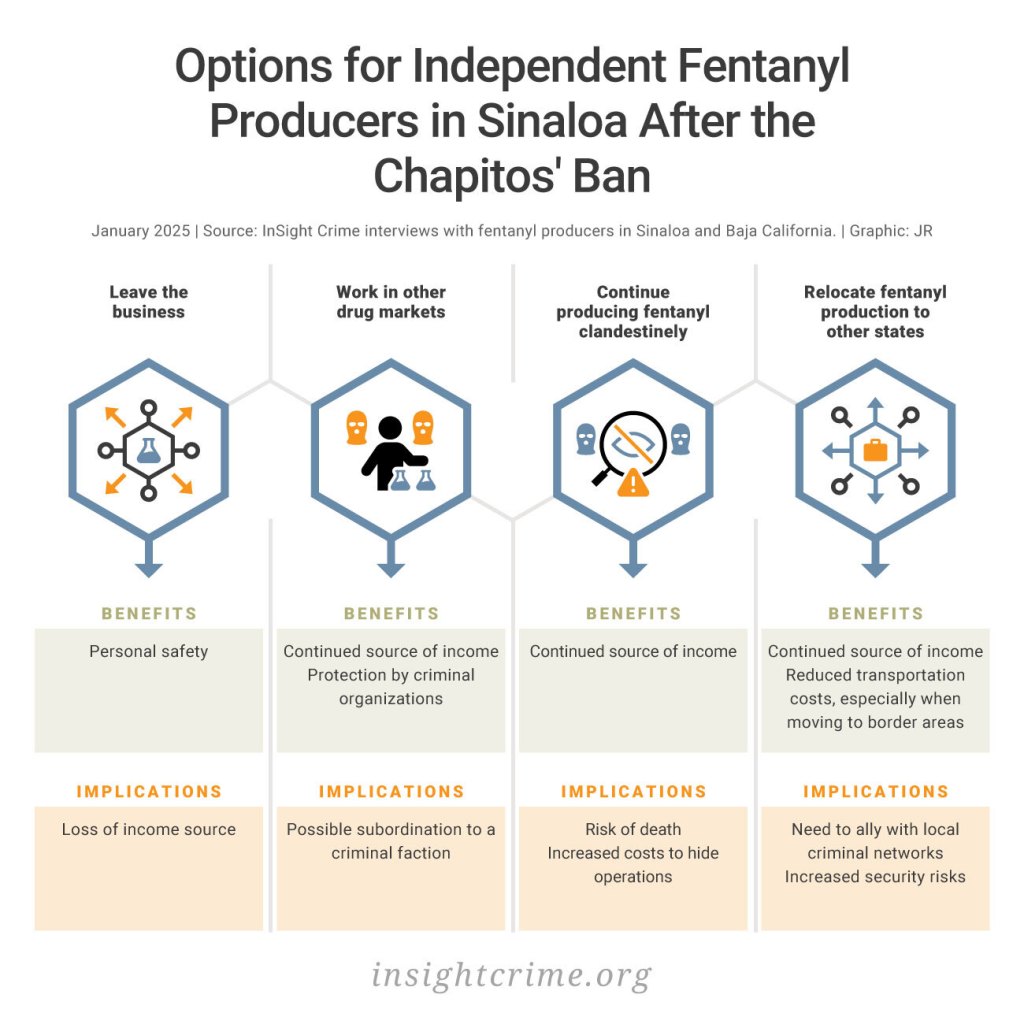

With the inability to continue operations in Sinaloa, some independent producers reportedly accepted offers from other criminal groups to continue their work elsewhere.

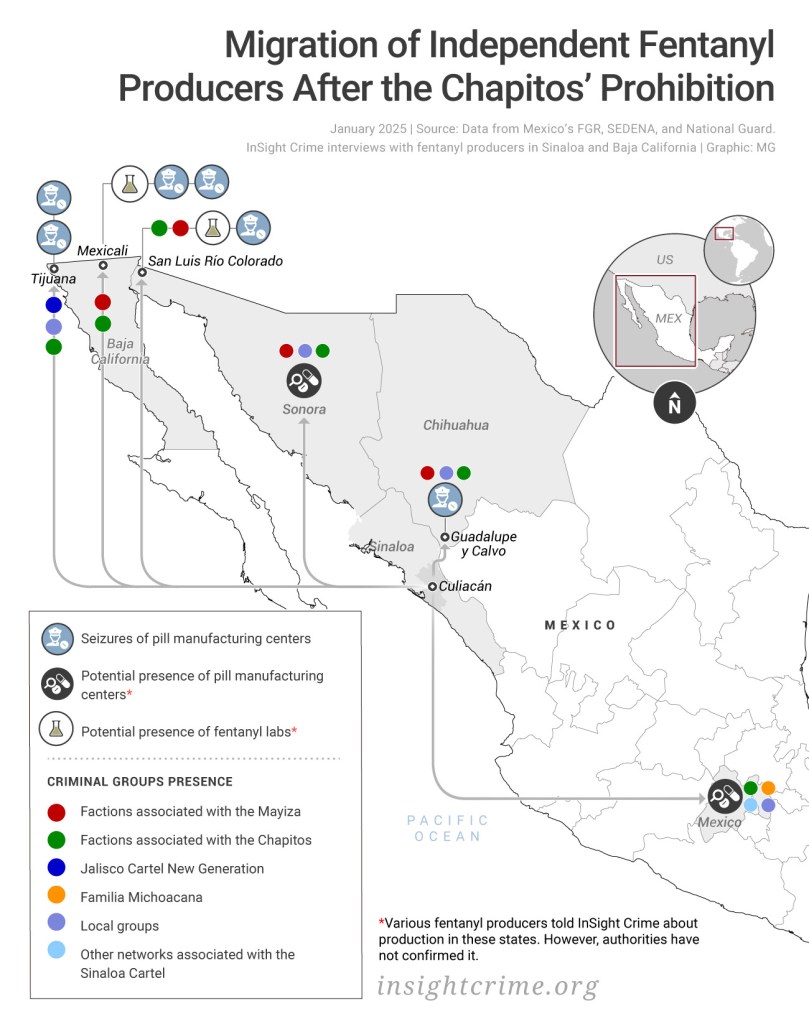

At least seven individuals involved in various aspects of the fentanyl trade in Sinaloa confirmed that these offers mainly came from groups operating in the northern states of Sonora and Baja California, close to the US-Mexico border.

These groups are largely under the umbrella of the Sinaloa Cartel, but are semi-independent and frequently engage in conflicts with one another. For example, in the limits between Baja California and Sonora, a region known as the Mexicali Valley, a faction associated with the Mayiza, called the Rusos, has been in regular conflict with groups loyal to the Chapitos. This rivalry has left numerous people dead, as well as led to threats against local authorities.

The offers to relocate and work with these groups were financially appealing. An independent producer interviewed in Culiacán stated he was offered a salary in Mexicali of approximately $1,200 per kilogram produced. Before the ban, that same amount had to be divided among six associates. He said that most of the producers he knew had taken these offers.

In some ways, moving production north did not significantly change the operational challenges. For instance, acquiring chemical precursors and other materials could still be done through the same contacts with Chinese suppliers. Criminal organizations in these territories could also provide infrastructure to facilitate the transportation of substances or could directly control the supply of these materials to producers, according to a fentanyl cook based in Mexicali.

Additionally, producing fentanyl closer to the border was strategic, as it reduced transportation costs from Sinaloa for these cartel factions.

However, operating in highly volatile territories with constant competition among different criminal organizations meant sacrificing independence. The producers we interviewed said migrating required “aligning” with one of these groups.

This alignment meant selling only to approved buyers, meeting production quotas, and investing more in security to protect against rival groups – an issue they did not face in Culiacán before the ban. Moreover, they had to adhere to strict orders to maintain a low profile.

“I just follow orders. I can’t afford to ask questions,” said a cook we interviewed in Tijuana.

For some producers, these risks were a necessary evil, particularly for those with limited experience in other drug markets in Culiacán.

“Many left simply because this [fentanyl production] is what they know how to do. They join other factions to keep doing the same thing,” said the producer currently serving a sentence at the Aguaruto Prison in Culiacán.

But for others, including Mario, the risks outweighed the benefits. For them, security was paramount. Prior to the ban in Culiacán, they had access to the protection networks established by the Chapitos, and they doubted they could obtain the same security in unfamiliar territory.

As a result, they returned to other ventures, such as methamphetamine and heroin production.

“I’m not leaving [Sinaloa]. I don’t know anyone there, and I wouldn’t know who I’m dealing with,” said the independent producer who had been offered a move to Mexicali.

Estimating how many producers chose to migrate is also difficult. During our fieldwork in Mexicali, we were in touch with four individuals who had relocated to produce fentanyl outside of Sinaloa. One of them claimed to know of three other labs in the area, in addition to his.

Once again, it’s not clear if Mexican authorities have identified these dynamics. For now, local authorities interviewed in Baja California, Chihuahua, and Sonora claimed they had no evidence of fentanyl production in their states.

Official statistics also do not provide any additional insights. Beyond not reporting fentanyl labs, no fentanyl precursor seizures have been recorded by SEDENA or the FGR in the border region since 2020, according to their responses to our information requests.

What is evident, however, is the proliferation of fentanyl confection centers. These are facilities where fentanyl paste, previously produced in labs, is pressed into tablets or other forms.

The lab coordinator interviewed in Culiacán said this proliferation is part of a strategy to avoid drawing attention in Sinaloa. According to him, some producers who remain active in the state with the Sinaloa Cartel’s permission limit their operations to producing fentanyl paste. With high opioid concentrations, only small quantities of paste are needed. They then sell this paste to cells in other states, which dilute it with cutting agents to produce large volumes of pills.

He claimed to oversee a network that runs pill production operations in Sonora and the State of Mexico using fentanyl paste sent from Culiacán. To operate in these territories, he said, “permission from Sinaloa Cartel factions” is always required, and previously negotiated with local actors.

There have been some public cases suggesting this dynamic. The most illustrative occurred in late October 2024, with the dismantling of a fentanyl confection center in San Luis Río Colorado, a border city in Sonora less than an hour’s drive from Mexicali. There, authorities found “various substances and machinery,” including pill presses.

At a press conference, Francisco Sergio Méndez, the regional delegate of the FGR in Sonora, stated that the fentanyl paste processed in that facility came from Culiacán.

According to official data from the national government, five additional centers have been found in Tijuana, Mexicali, and Guadalupe y Calvo, since 2023.

In spite of these shifts in production patterns – as well as upheaval and infighting within the Sinaloa Cartel – it remains unclear to what extent other criminal organizations in the country are entering fentanyl production.

While the DEA has also implicated the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación – CJNG) in large-scale fentanyl production, public evidence of their involvement is limited. It rather suggests the group primarily obtains fentanyl from producers in Sinaloa.

For instance, the only fentanyl precursor seizure recorded in the state of Jalisco by federal authorities occurred in 2020, involving 50 kilograms of NPP in the municipality of Tlajomulco, according to data obtained by InSight Crime. In December 2024, the FGR reported destroying ANPP and fentanyl pre-precursors in Jalisco, but did not offer information about where these were seized.

And while a recent sanctions document by the US Treasury Department targeted a CJNG opioid trafficking network and an alleged cartel operative who was indicted by the United States, the Treasury Department acknowledged that the group “receives fentanyl from a husband-and-wife duo based in Sinaloa.”

InSight Crime’s fieldwork in Guadalajara, Jalisco, in April 2024, found the same. We interviewed three individuals involved in CJNG drug trafficking operations, and they all said that “fentanyl comes from Sinaloa.”

Interviews conducted in late 2022 in Michoacán, another state where the CJNG and dozens of other smaller groups have a presence, also revealed that those who had begun trafficking fentanyl sourced it through intermediaries connected to Sinaloa. Follow-up visits to the state in 2023 and 2024 found no evidence of a shift in this dynamic.

Adapting Production Methods

Fentanyl producers in Mexico are on a steep learning curve, partly driven by increasingly strict regulations and enforcement over the supply chain of precursor chemicals.

A similar process occurred in Mexico’s methamphetamine market. Starting in the late 2000s and early 2010s, Mexican producers transitioned from relying on highly regulated precursor chemicals imported from abroad to synthesizing them locally from less regulated pre-precursors and other essential chemicals.

While Mexico’s fentanyl market has not yet fully reached this stage, producers seem to be heading in that direction.

The most recent regulatory changes came in August 2024, when China imposed stricter controls on 1-BOC-4-AP and 4-AP, two substances widely used as fentanyl pre-precursors by producers in Sinaloa, according to our interviews and US law enforcement investigations.

During our fieldwork in Sinaloa that month, sources reported that access to these substances had become increasingly difficult over the past year, leading to occasional production shortages.

This was not the first time producers faced such challenges. When fentanyl production began in Mexico, producers reportedly relied on ANPP and NPP. However, after China implemented stricter controls on these chemicals in 2019, several producers shifted to using other substances provided by Chinese suppliers, such as 4-Piperidine, 1-BOC-4-piperidone, 4-AP, and 1-BOC-4-AP.

Following the most recent restrictions, producers adapted once again.

According to several producers we interviewed, the first adjustment was to increase the volume of fentanyl they had already produced by mixing it with other substances. These included xylazine, a non-opioid sedative mainly used in veterinary medicine.

The mixture reportedly allowed producers to compensate for the fentanyl shortage they were temporarily facing while still producing a substance with a depressant effect.

Obtaining xylazine was not difficult. While the sedative is legally accessible in Mexico only to veterinarians or with a prescription, two veterinary industry sources indicated that diversion of xylazine is common. They added that this was due to a lack of resources, corruption, or coercion towards health authorities.

For example, the synthetic drug lab coordinator we interviewed in Culiacán explained that his production cell obtained xylazine through contacts at rodeos in rural Sinaloa. These contacts justified their purchases by claiming they needed to treat horses. They would buy excess quantities and sell the surplus.

It is also possible that production networks sourced xylazine from abroad. In May 2024, a court in the Central District of California indicted the Chinese chemical company Hubei Aoks Bio-Tech Ltd. and three of its senior employees for selling fentanyl precursors and xylazine that authorities claim were to be used for the production of illicit drugs.

According to the press release, Mexico was one of their most profitable markets. The company, “Tailored their precursor recommendations … and would suggest alternative chemicals if one was not available.”

In a previous case in October 2023, US authorities unsealed a series of indictments from Florida-based courts against several Chinese companies sending controlled substances to Mexico and the United States. Among them was Hanhong Medicine Technology Company, which US authorities accuse of sending xylazine and fentanyl precursors to “a drug trafficker in the Sinaloa Cartel.”

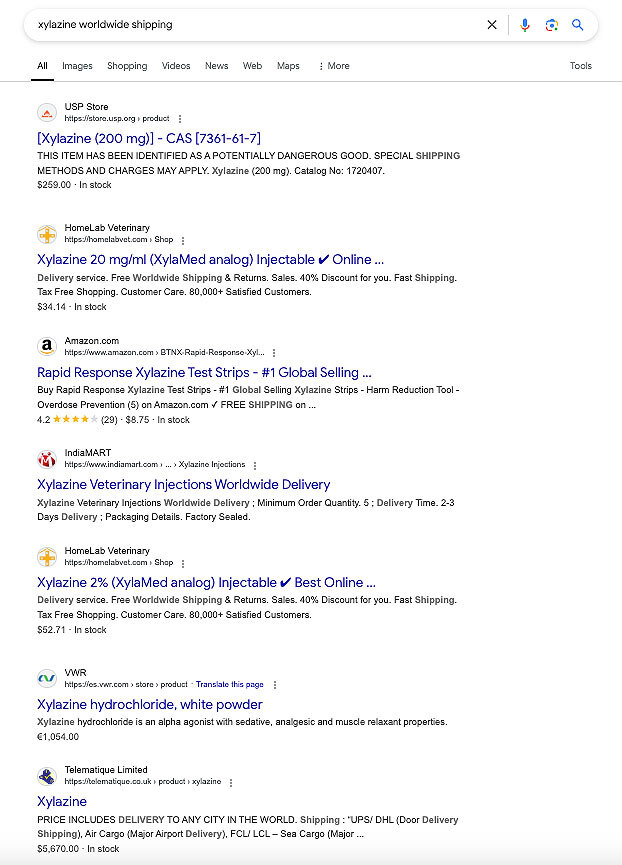

In our own research, we found many websites on the clearnet selling xylazine and shipping it abroad. A simple Google search for “xylazine worldwide shipping” conducted from Mexico yielded several results from websites in China, India, and European countries. (See below)

Although most of them advertised the substance for veterinary purposes, they appeared to sell it without asking customers for specific requirements.

Results for a Google search on “xylazine worldwide shipping” conducted from Mexico in January 2025.

Results for a Google search on “xylazine worldwide shipping” conducted from Mexico in January 2025.

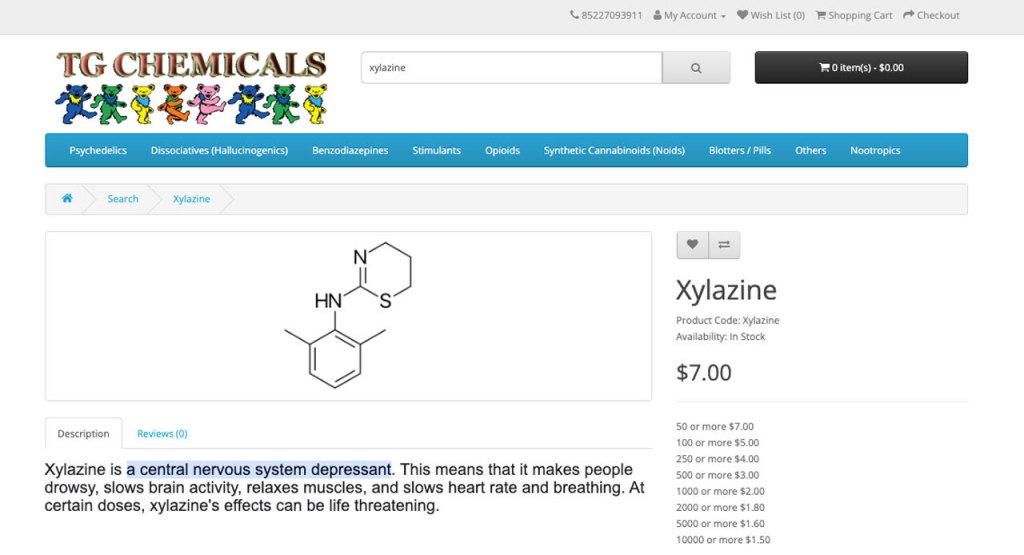

There were also websites specifically advertising it as a drug. For example, a Chinese website called TG Chemicals, which we previously identified as a precursor chemical purveyor, described xylazine as a substance fit for human consumption.

“It makes people drowsy, slows brain activity, relaxes the muscles, and slows heart rate and breathing,” reads the product description, which was selling it for as little as $7 per 5 milliliter and promised worldwide shipping.

The Chinese chemical company TG Chemicals advertises xylazine as a substance for human consumption. This screenshot was taken in October 2024.

The Chinese chemical company TG Chemicals advertises xylazine as a substance for human consumption. This screenshot was taken in October 2024.

To be sure, the mixing of xylazine with fentanyl could occur at any stage of the supply chain and has likely been happening in the US fentanyl market for several years, particularly at the retail level.

For its part, the DEA’s National Forensic Laboratory System began detecting a surge of xylazine in fentanyl samples as early as 2019, when Mexican drug trafficking networks were still in the early stages of fentanyl production.

US prosecutors have also linked direct sales of xylazine from China to the United States. In the 2024 case against Hubei Aoks Bio-Tech Ltd., investigators also documented the illicit sale of at least 2 kilograms of xylazine by the company to the United States, with shipments dating back to 2016.

It remains uncertain whether Mexican producers have now systematized the use of xylazine or if it is only used as a stopgap measure to deal with current shortages. As of late 2024, Mexican authorities had not reported any xylazine seizures.

However, harm reduction organizations Prevencasa A.C. and Verter A.C., based in the border cities of Tijuana and Mexicali respectively, have observed its growing presence in the local fentanyl market. Through regular drug testing, they began detecting xylazine in samples as early as October 2023, according to our interviews with their staff.

And in an April 2024 study, conducted with researchers from Mexico’s National Institute of Psychiatry (Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría), these organizations reported that 20% of the fentanyl samples analyzed in both cities contained xylazine.

(When we conducted interviews with staff from both organizations in August 2024, they noted a temporary decline in xylazine-positive samples, though it remained unclear whether this was indicative of a sustained reduction or a short-term fluctuation.)

Drug testing initiatives in the United States have also increasingly detected high concentrations of bis(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidyl) sebacate, or BTMPS, in fentanyl samples. This industrial-grade chemical, primarily used in the plastics industry, is widely advertised on Chinese chemical websites targeting Spanish-speaking customers. Although our sources in Sinaloa did not report familiarity with the substance, drug policy experts cited in US media have noted its presence nationwide, suggesting that the mixing of BTMPS with fentanyl is occurring at the production stage in Mexico.

Meanwhile, in Culiacán, fentanyl producers had also begun adapting to supply chain disruptions. During our visit in August 2024, sources reported the adoption of a new pre-precursor chemical sourced from China to substitute for the ones recently scheduled.

“A new formula is being used, it is bought from China along with the chemicals,” said one of the producers.

All of our sources declined to provide details or specific names, either because they were not authorized to do so or wanted to avoid attracting the attention of authorities. So, we turned to Chinese chemical companies operating on the clearnet and dark web to see if we could find this information.

To do this, we reconnected with vendors we had spoken to during a previous investigation into the precursor chemical trade from China in 2023 and early 2024.

We found that many of the sites we had previously identified – including TG Chemicals – continued to operate under the same names and usernames. And while other platforms had gone down, new ones had appeared, had merged with other platforms, or had simply switched sites.

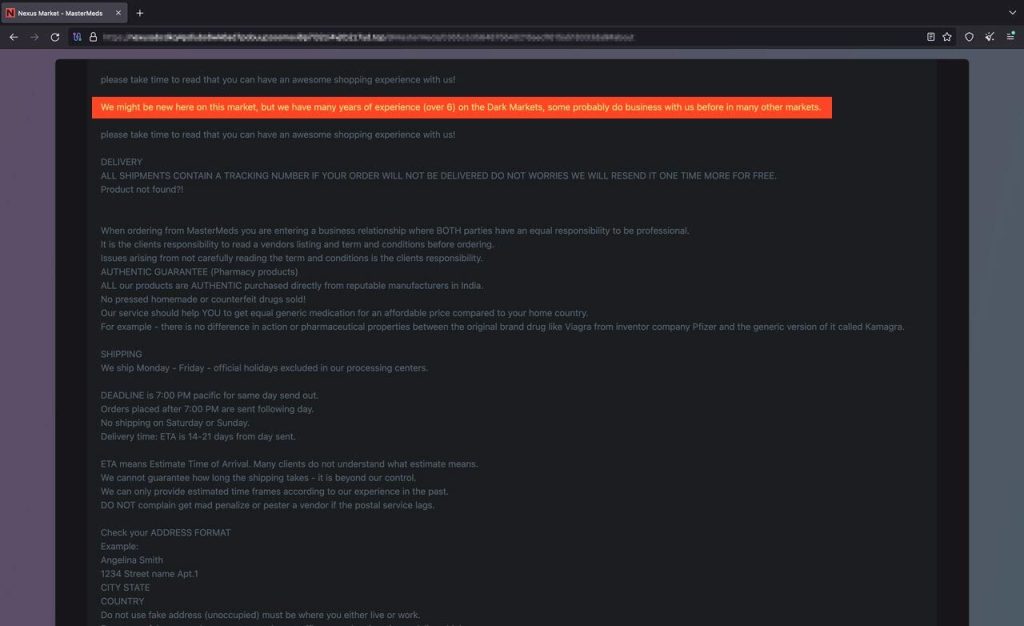

For example, one China-based seller of various controlled substances on the dark web, MasterMeds, wrote, “We might be new here on this market, but we have many years of experience (over 6) on the Dark Markets. Some probably do business with us before in many other markets.”

MasterMeds, a website selling controlled substances on the dark net, claims to have been operating for over six years. This screenshot was taken in October 2024.

MasterMeds, a website selling controlled substances on the dark net, claims to have been operating for over six years. This screenshot was taken in October 2024.

Still, although they were still operational, they were also less responsive, more skeptical of our questions, or sometimes intentionally evasive.

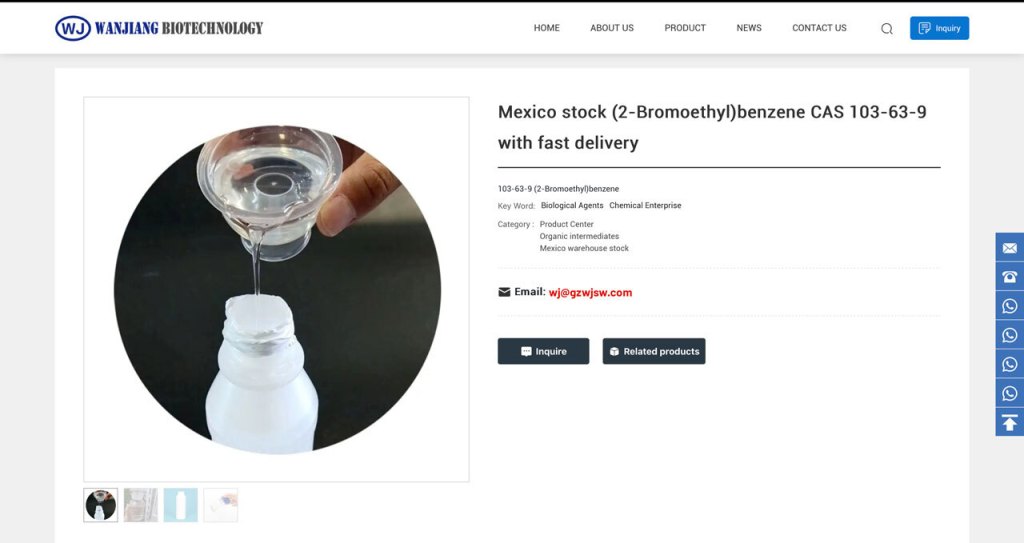

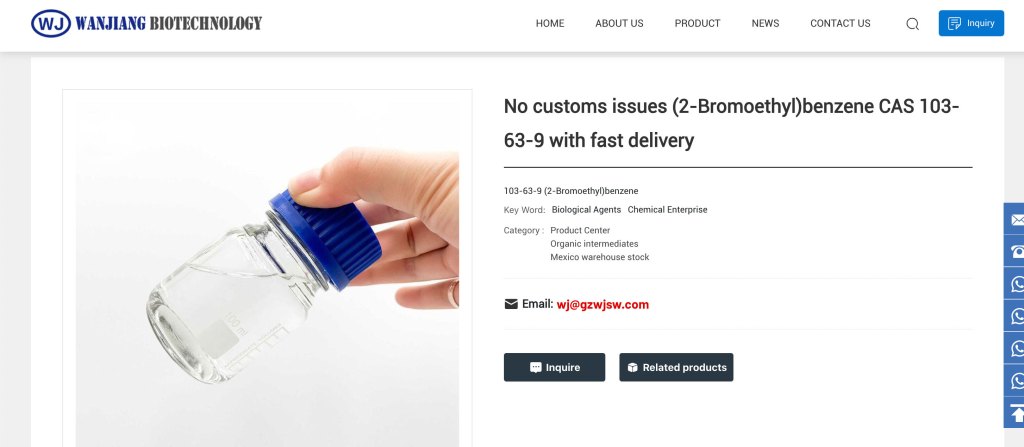

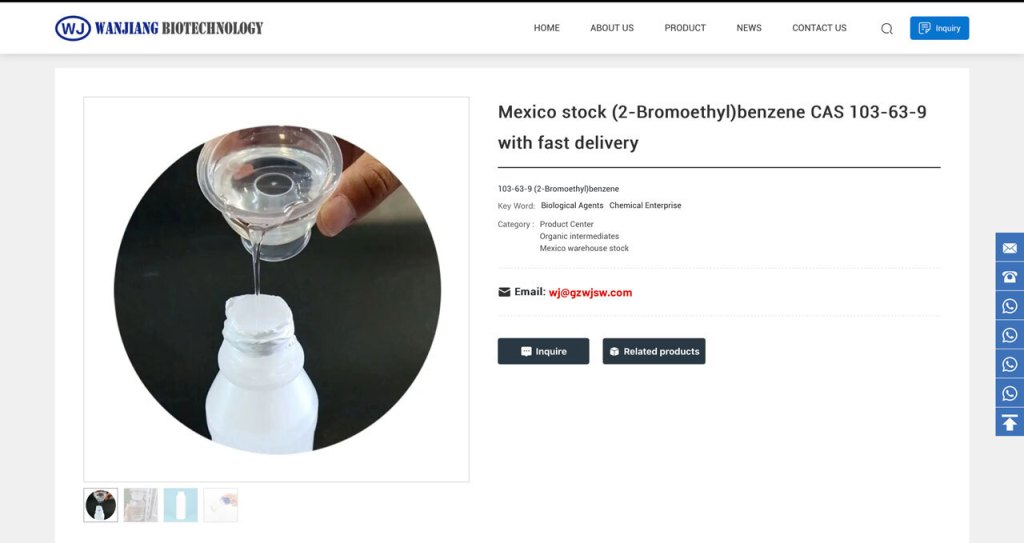

Whereas before, we connected within days, this time it took four months before we finally received a reply from a seller. The company, Wanjiang Biotechnology, had spoken to us before, and we asked if they were still selling “222” and “79” – codes for 1-BOC-4-AP and 1-BOC-4-Piperidone, the chemicals that fentanyl producers in Mexico said were scarce following the implementation of the new regulations in China in August 2024.

They responded that they were still selling those products, but they also suggested alternatives – specifically, CAS 109384-19-2, which refers to 1-Boc-4-hydroxypiperidine, and CAS 103-69-9, or (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene. The reason, according to the seller, was that it had a better price and higher quality, which they claimed was “an improvement” on the previous substances used to manufacture fentanyl.

For example, 222 (1-BOC-4-AP) was priced at $700 per kilogram for orders of 15 kilograms, with a slight discount bringing the price to $650 per kilogram for orders of 20 kilograms. Its counterpart, 79 (1-BOC-4-Piperidone), was offered at $400 per kilogram for 15 kilograms and $350 for 20 kilograms.

Meanwhile, 1-BOC-4-hydroxypiperidine was sold for $190 per kilogram, with a minimum order of 25 kilograms. (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene was the cheapest option, with a minimum price of $65 per liter for orders of 100 liters.

Another benefit was the lack of restrictions over their sale. While (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene is currently monitored in Mexico for its dual use, and the DEA submitted a request in October 2024 to schedule it as a List I Chemical, it is not controlled in China. Meanwhile, as of December 2024, 1-Boc-4-hydroxypiperidine is not scheduled in China, Mexico, or the United States.

We also asked the seller if they could explain how to use these chemicals to produce fentanyl. Unlike our previous interactions with them last year, they refused to share the recipe. Instead, they insisted that the purchase be complete first. As it was during our previous interactions, payment options were limited to cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin, USDT, TRC20, and ERC-20.

To encourage the purchase, they aggressively emphasized the superior quality of their product. For example, the vendor criticized the potency of Mexican-made products, claiming they required mixing multiple substances, which was both costly and inefficient. In contrast, they boasted that their products had “strong quality.”

Afterward, we asked about shipping to Mexico. The vendor claimed they could ship through standard courier services, guaranteeing “100% delivery.” They added that shipments could be sent from China or from their warehouses in Hong Kong, Australia, the United States, or Europe.

They ended the email with another push: “Will you order 25kg of 109384 this time? What is your payment method?”

We did not respond further.

On their website, they advertised “Mexico stock” of (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene, promising “fast delivery” and “no customs issues.” They also published photos demonstrating how the product could be packaged for international shipment.

Wanjiang Biotechnology advertises a ‘Mexico Stock’ of (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene. The screenshots were taken in January 2025.

Wanjiang Biotechnology advertises a ‘Mexico Stock’ of (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene. The screenshots were taken in January 2025.

Wanjiang Biotechnology advertises a ‘Mexico Stock’ of (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene. The screenshots were taken in January 2025.

Wanjiang Biotechnology advertises a ‘Mexico Stock’ of (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene. The screenshots were taken in January 2025. Wanjiang Biotechnology advertises a ‘Mexico Stock’ of (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene. The screenshots were taken in January 2025.

Wanjiang Biotechnology advertises a ‘Mexico Stock’ of (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene. The screenshots were taken in January 2025.

Wanjiang Biotechnology advertises a ‘Mexico Stock’ of (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene. The screenshots were taken in January 2025.

Wanjiang Biotechnology advertises a ‘Mexico Stock’ of (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene. The screenshots were taken in January 2025.

Wanjiang Biotechnology advertises a ‘Mexico Stock’ of (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene. The screenshots were taken in January 2025.

Wanjiang Biotechnology advertises a ‘Mexico Stock’ of (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene. The screenshots were taken in January 2025.

We were unable to confirm with the producers in Culiacán if these were the new substances they had mentioned. However, recent seizures point to this possibility. On November 20, 2024, Mexico’s National Guard and the National Customs Agency (Agencia Nacional de Aduanas de México – ANAM) seized 27.4 kilograms of (2-Bromoethyl) Benzene, originating from Hong Kong, at a courier company in Toluca, Mexico State.

According to official records, this marked the first reported seizure of this substance in the country.

Experimenting With New Synthetic Drugs

Mexican fentanyl producers are beginning to show early signs of involvement in new synthetic drug markets, in an apparent effort to diversify and keep up with global trends.

Two sources in Culiacán, for example, revealed they had recently started producing “tusi,” which draws its name from the chemical mixture 2C-B. Often referred to as “pink cocaine,” tusi now includes various combinations of synthetic drugs, typically blending a stimulant and a depressant. In Culiacán, sources told InSight Crime that the most common mixture they were employing included fentanyl, methamphetamine, benzodiazepines, caffeine, and paracetamol.

Tusi is gaining significant popularity across Latin America, but the market in Mexico is still emerging. Mexico’s National Guard has reported only a single seizure of tusi, totaling 500 grams. Dealers currently target a high-end market in Mexico, the producers said, with a single dose costing upwards of $100.

“Right now, it’s a small business, but I think it will grow. The profits are very good,” said a tusi producer we interviewed in the Culiacán area.

Meanwhile, mixtures of methamphetamine and fentanyl are also being produced in Mexico for broader and more accessible markets, often without users’ knowledge. Staff at various treatment centers in Baja California, Sonora, and Chihuahua interviewed by InSight Crime reported an apparent rise in these mixtures within local drug supplies.

“I’m seeing more and more fentanyl patients who thought they were only using crystal meth,” said José Luis Haro Méndez, director of the treatment center CIAAR in Nogales, Sonora.

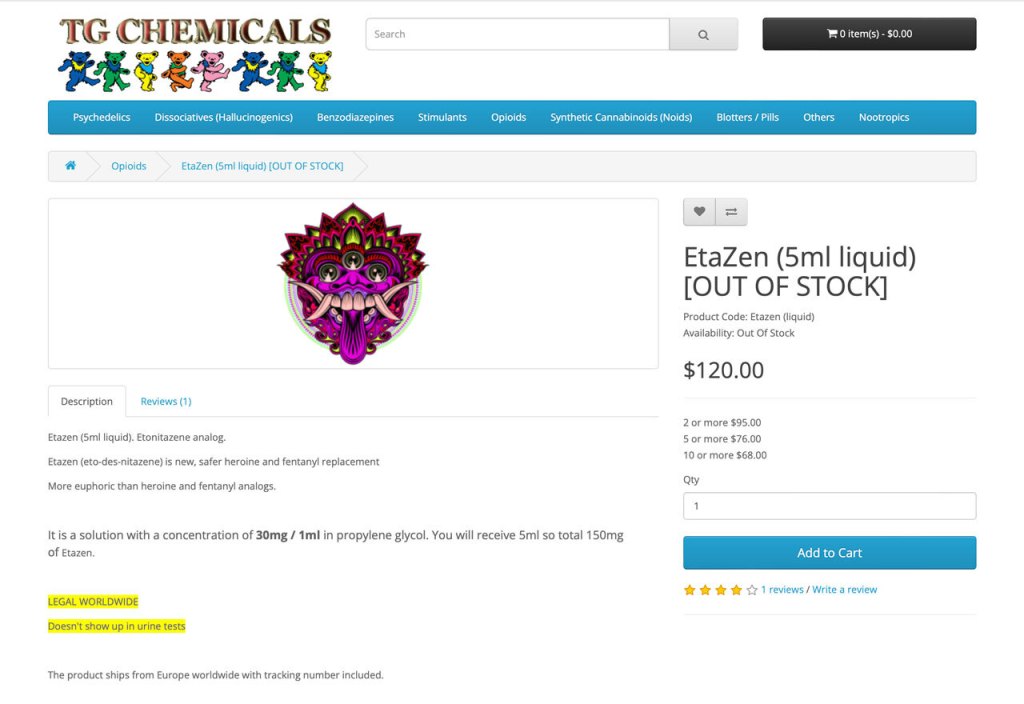

Another emerging concern is the possible entry of Mexican producers into new synthetic opioid markets. A recent United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) report noted a decline in the presence of new fentanyl analogues in global illicit markets in 2023 compared to previous years. However, authorities have observed a rise in nitazenes – a class of synthetic opioids, with some analogues up to 43 times more potent than fentanyl.

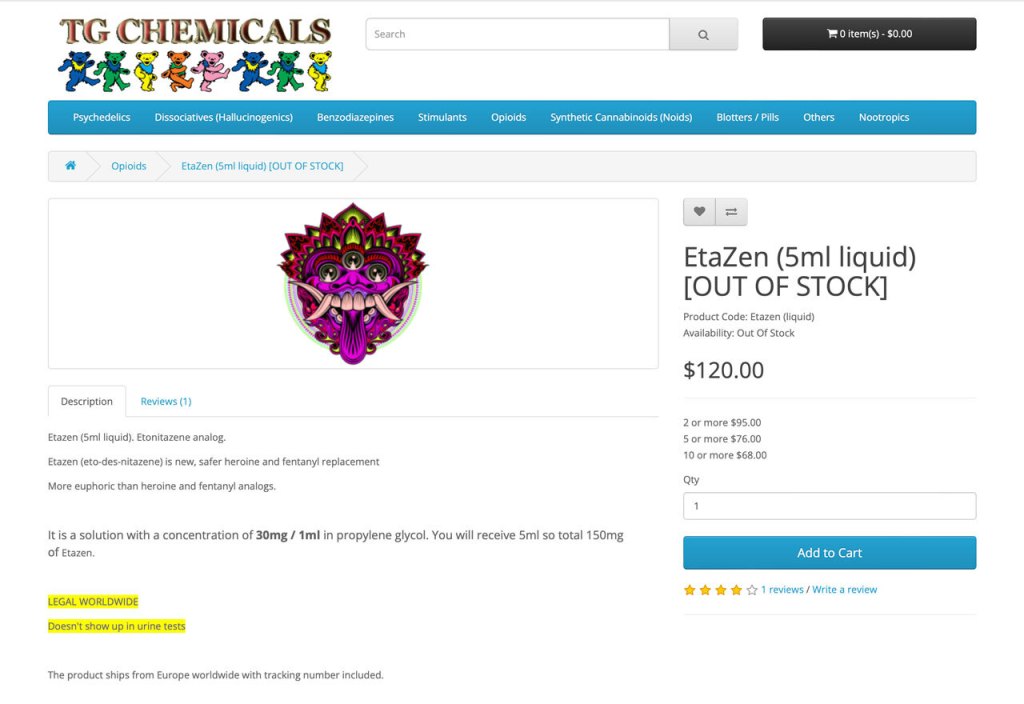

Nitazenes are not new. They were first synthesized as a substitute for morphine in the 1950s by a Swiss pharmaceutical company but were never approved for clinical use. And since 2019, the UNODC has reported their presence in drug markets, noting a rapid spread in recent years of analogues, such as isotonitazene, metonitazene, etazene, and protonitazene.

The drugs have already unleashed havoc across at least 30 countries, according to UNODC data. In the United Kingdom, for example, authorities recorded 284 nitazene-related deaths between June 2023 and August 2024. Moreover, Canadian authorities recently seized fake oxycodone pills – which have traditionally been laced with fentanyl – that tested positive to protonitazene. And while the United States has limited public data on nitazene-related deaths, the DEA reported in January 2024 that its forensic lab had received 4,300 reports about these opioids since 2019.

The evidence of Mexican producers’ involvement in this market is currently limited and perhaps in the early stages. For their part, Mexican authorities have not reported any seizures of nitazenes, and have not issued alerts about their presence in the drug supply. Similarly, all US judicial cases involving nitazene distribution and trafficking that we could find showed no connections to Mexico. (In the only publicly available transnational case we could find, US prosecutors charged a Chinese pharmaceutical company called Jiangsu Bangdeya New Material Technology Company, and its owner Jiantong Wang, with shipping 9 kilograms of protonitazene and 6 kilograms of metonitazene directly to a drug trafficker in Southern Florida between April 2022 and June 2023.)

In our fieldwork in Sinaloa and Baja California, we found that local producers were already familiar with the names of the substances, and some even claimed to have bought them from China. Yet, their understanding seemed limited. For example, three producers referred to protonitazenes and etazenes as “precursors” for fentanyl or as compounds they could use in the formula, not as separate opioids.

“It’s all part of the same thing. It’s part of the fentanyl component,” said the lab coordinator in Culiacán.

Another producer based in Culiacán said he had heard of nitazenes, and knew about other producers who bought them from China, but, he said, “I don’t understand how to use them.”

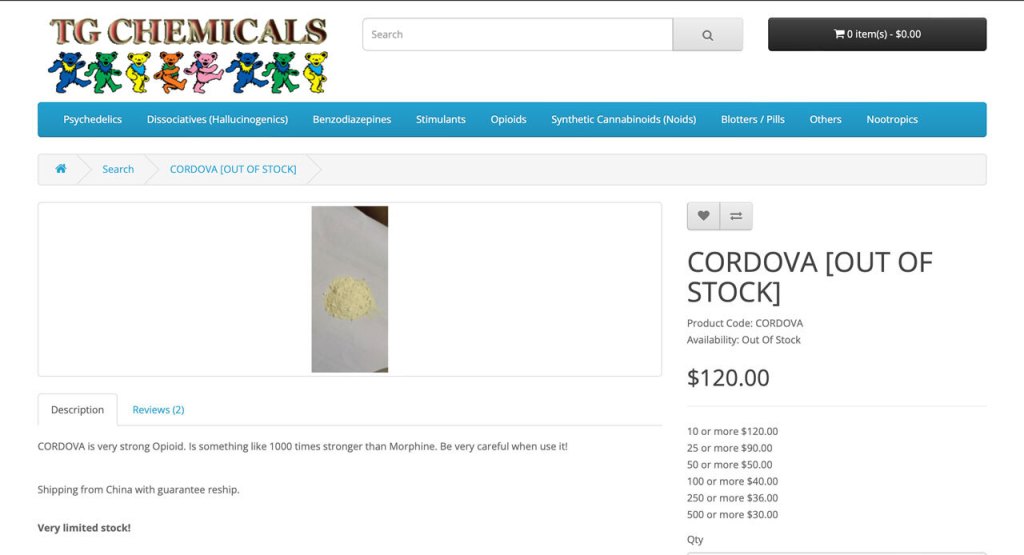

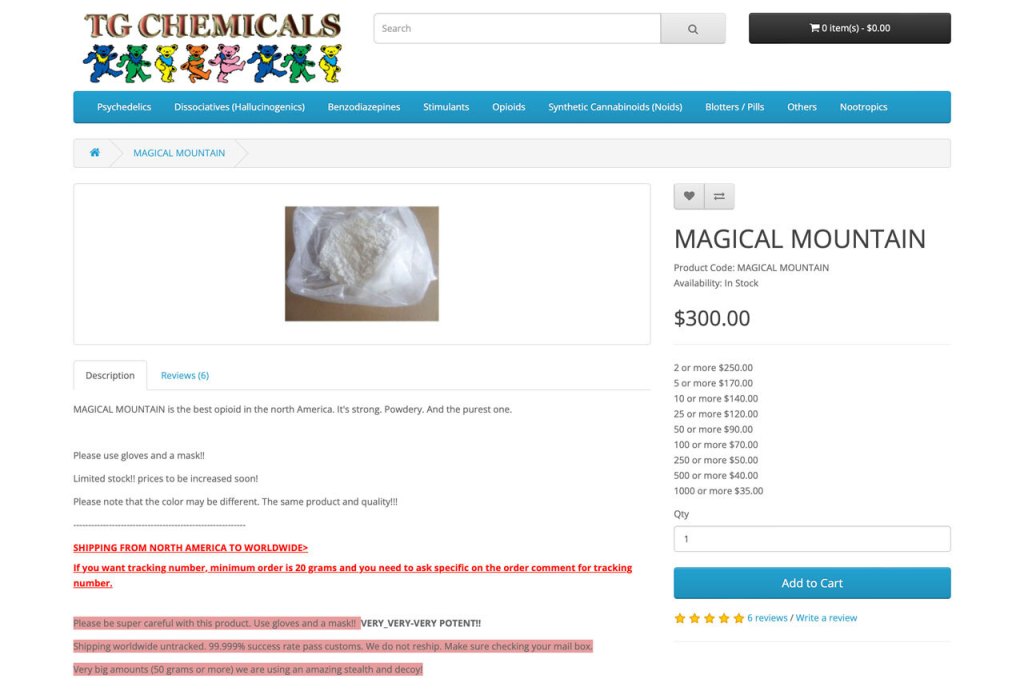

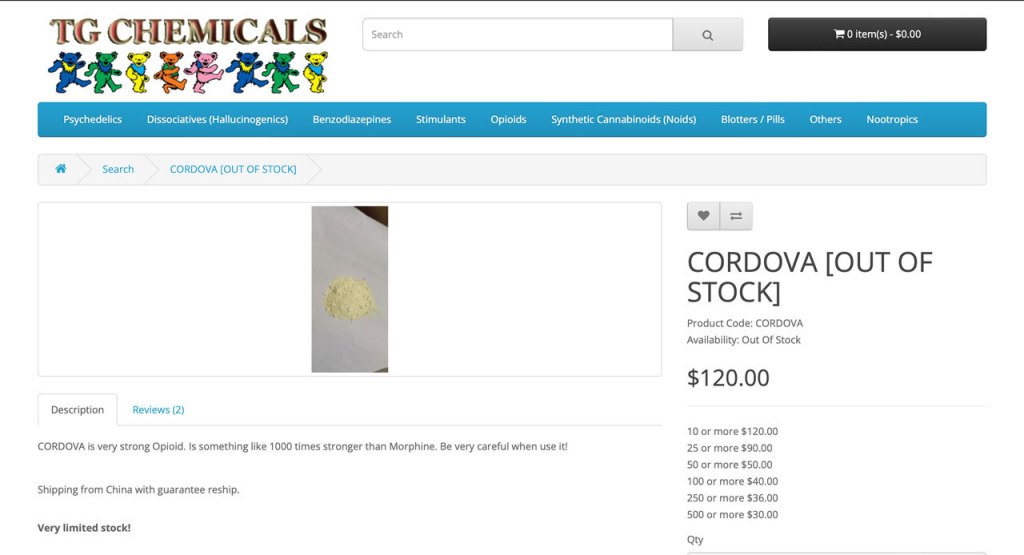

Still, in our research into dark web and clearnet sites, we found that the novel synthetic opioid market was well advanced. Sellers, mainly in China, but also operating in other regions of the world, actively advertised various types of nitazenes as the “newest and strongest opioids.”

For instance, TG Chemicals features various advertisements for etazenes on their website, describing them as “more euphoric than fentanyl analogues.” And, more recently, they have uploaded dozens of other advertisements for other synthetic opioids, which they claim to be stronger.

One product, called CORDOVA, supposedly shipped from China, was touted as a thousand times stronger than morphine. Another, Magic Mountain, was described as “the best opioid in North America,” with promises of “untracked shipping,” and a safety warning because it is “very very very potent.”

The Chinese chemical company TG Chemicals advertises various opioids on its website. The screenshots were taken in November 2024.

The Chinese chemical company TG Chemicals advertises various opioids on its website. The screenshots were taken in November 2024.

The Chinese chemical company TG Chemicals advertises various opioids on its website. The screenshots were taken in November 2024.

The Chinese chemical company TG Chemicals advertises various opioids on its website. The screenshots were taken in November 2024.

The Chinese chemical company TG Chemicals advertises various opioids on its website. The screenshots were taken in November 2024.

The Chinese chemical company TG Chemicals advertises various opioids on its website. The screenshots were taken in November 2024.

The Chinese chemical company TG Chemicals advertises various opioids on its website. The screenshots were taken in November 2024.

The Chinese chemical company TG Chemicals advertises various opioids on its website. The screenshots were taken in November 2024.

The Chinese chemical company TG Chemicals advertises various opioids on its website. The screenshots were taken in November 2024.

The Chinese chemical company TG Chemicals advertises various opioids on its website. The screenshots were taken in November 2024.

The prices of these new opioids also seem attractive for buyers, although they vary based on shipment origin, dosage, and vendor. Some orders from China can be as cheap as $50 for a few grams. The price decreases if the buyer buys in bulk. The most expensive ones we found cost up to $9,000 per kilogram, and mostly came from sellers on the dark web, allegedly operating out of North America and Europe.

We reached out to some of them to inquire about their products. The only one that responded was behind a dark website called MethCrystals, which sold different drugs and claimed to ship from California.

In their communications with us, the seller implied that they regularly shipped to Latin American countries, and they claimed to have just sold 4 kilograms of protonitazene to a buyer in Venezuela. When asked, the seller declined to give information about his clients.

“We do not disclose information about our clients under any pretext,” the MethCrystals website read.

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus