The quartet of judicial terror

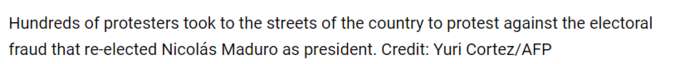

From their anti-terrorism courts in Caracas, four improvised judges have dedicated themselves to, precisely, spreading terror.

They act in an expeditious and implacable manner, amidst arbitrariness and without stopping at formalities, not only in concert with the government of Nicolás Maduro, but also remote-controlled from the Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice and the Criminal Circuit of Caracas. Their purpose: to give exemplary punishments to those who express their disagreement with electoral fraud.

In a recent meeting of the judicial branch of the Nicolás Maduro regime, headed a few days before the presidential elections by the pro-government Attorney General, Tarek William Saab, together with the current President of the Criminal Circuit of Caracas and former prosecutor, Katherine Haringhton, some details were fine-tuned of the repressive machine that was to be activated as soon as the fraudulent proclamation of Maduro as re-elected president of Venezuela was consummated, which in fact occurred at the close of the electoral day on July 28.

With the working hypothesis that the impending electoral-judicial maneuver would provoke protests, the participants set out to design measures to prevent or calm them. The brute force and cruelty of the security forces would have to be deployed in the streets, of course, but among the twists that were prepared was the activation of a second line of attack: the Terrorism Courts, a novel jurisdiction that Chavismo-Madurismo established in 2012 and that, for at least three years, began to act as a virtual task force to expeditiously and relentlessly prosecute any person identified as an opponent.

The four judges in charge of the case have been acting from Caracas for the past four weeks. They have not turned their backs on their mission; in fact, they follow to the letter a common pattern of arbitrary actions that is chilling: they deny access to the files of the detainees, who are prosecuted without consideration, without the possibility of appointing trusted lawyers, always behind bars, outside and far from their natural jurisdictions, sometimes in groups - therefore, without considering the circumstances of each individual case - and telematically.

When Venezuelan Carlos Armando Figueredo translated The Jurists of Horror , Ingo Müller’s classic about justice in Nazi Germany, a few years ago, he perhaps did not imagine that this historically grounded warning would be reincarnated in his own country through judges Carlos Liendo, Ángel Betancourt, Franklin Mejías and Joel Monjes. A fifth judge, Edward Briceño, has managed to maintain a low profile that is resistant to scrutiny.

Constituted in a terror machine, the four judges in this story are part of a punishment operation that, according to sources consulted by Armando.info , is being carried out under the remote direction of Judge Elsa Gómez Moreno, from the Criminal Cassation Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice (TSJ). The judge is close to Cilia Flores, wife of Nicolás Maduro. The connection between Gómez Moreno and the First Lady or First Combatant , as the revolutionary jargon prefers to call her, goes through the judge’s niece, Jennifer Karina Fuentes, who was the partner of Walter Gavidia Flores, son of Cilia Flores.

And instruction is not always remote. On August 3, just six days after the presidential elections, as she revealed on her Instagram account , Judge Gómez Moreno toured with Haringhton “the Courts with Jurisdiction in Cases Linked to Crimes Associated with Terrorism with Jurisdiction at the National Level (...) with the purpose of strengthening the processes implemented by each court in the development of efficient justice.” This is evidence of the key role that the regime has granted to this jurisdiction to quell any revolt in the current circumstances.

Fast and furious

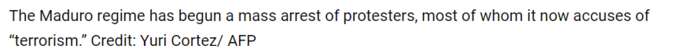

The terrorism courts are a jurisdiction created with few legal elements by the TSJ since 2012. Living up to its name, it was conceived to judge cases related to organized crime and terrorism. But almost since its creation, and especially now, it has been stretching the classic meaning of the word “terrorism” - that is, any violent act that seeks to generate terror in the population - to reach a broader definition that includes any act of opposition to the regime of Nicolás Maduro.

Impartiality is not, therefore, one of the requirements for presiding over these courts. And one judge who boasts, without blushing, of his closeness to Maduro himself is Carlos Enrique Liendo Acosta, head of the 2nd Control Court against Corruption and Terrorism.

A couple of sources point out that the event that marked a turning point in the career of the lawyer Liendo Acosta, which had been rather grey until then, was his appointment as provisional prosecutor in the 40th Prosecutor’s Office of the Metropolitan Area of Caracas. It was quite a stroke of luck. In those roles he made friends with Katherine Haringhton, sanctioned by Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the European Union under accusations of being “responsible for undermining Democracy and the Rule of Law in Venezuela, among other things by initiating politically motivated prosecutions and not investigating allegations of human rights violations committed by the Maduro regime.” An early judicial ally of Chavismo, in the role of prosecutor of the Public Ministry she was the accuser in high-profile cases , such as those of the former mayor of Caracas, Antonio Ledezma, and the opposition leader, María Corina Machado. Today Haringhton serves as the presiding judge of the Criminal Circuit of Caracas.

In the short time he has been at the head of the court assigned to him, Liendo Acosta has earned the reputation of being “the most implacable” among his peers in the anti-terrorist justice system. In keeping with that reputation, he is entrusted with the most outstanding and politically significant proceedings. On his desk, for example, is the case of the so-called Operation White Bracelet , by which an attack against Nicolás Maduro and the overthrow of the government were supposedly planned for 2023. Liendo Acosta’s efforts in the case have led to the imprisonment of thirty military personnel, including Captain Anyelo Heredia , and the lawyer and activist Rocío San Miguel, whom the court links to the alleged plot and accuses her of the crimes of treason, conspiracy and, of course, terrorism.

Already during the political and public order crisis unleashed by the presidential elections, Liendo Acosta lent his hand to raising a judicial siege around María Corina Machado. For example, he was the one who charged Juan Freites, Luis Camacaro and Guillermo López, regional heads of the campaign command of the Vente Venezuela party, which Machado leads, who were arrested in January of this year and whose lawyers Liendo has not allowed to be sworn in to date.

The cases of journalist and community leader Carlos Rojas and leader of the Voluntad Popular party, Jeancarlos Rivas, have also been in the office of Liendo Acosta since this year, who has denied their lawyers access to the files.

The regime’s confidence in Liendo Acosta was made clear this year when he was tasked with prosecuting senior Chavista officials who fell into disgrace after their alleged involvement in the Pdvsa-Cripto case , including former minister and former vice president of the Republic, Tareck El Aissami; Simón Zerpa, former president of the Central Bank of Venezuela; Joselit Ramírez, former head of the closed National Superintendency of Cryptoassets; Hugbel Roa, former Chavista deputy; and Antonio Pérez Suárez, an Army officer and former vice president of Commerce and Supply of the state-owned Pdvsa.

The prosecutor’s confidence

Regarding Ángel Betancourt Martínez, official documents show that since he was 28 years old, the young judge, now 36 years old, was making his way in the Venezuelan justice system, permeated by the whims and mandates of the Executive Branch and the ruling party. Then, in September 2017, he was appointed provisional prosecutor by the Vice-Attorney General of the Republic, serving for the Directorate of Common Crimes of the Judicial District of Vargas State (now La Guaira).

Shortly after, in January 2018 , from the 59th Prosecutor’s Office of the Public Prosecutor’s Office with National Jurisdiction, he had his first major political action by requesting the start of extradition proceedings from Spain of Rolando José Figueroa Martínez, a member of Voluntad Popular.

In November of that same year, he was appointed prosecutor with national jurisdiction. Two sources consulted indicate that, as a prosecutor, Betancourt was a very efficient official for the Chavista cause and that he thus became part of Tarek William Saab’s circle of trust, which catapulted him in 2023 as head of the State Court of First Instance in Control Functions of the Metropolitan Area of Caracas. The same sources assure that it was Saab who nominated him shortly before the elections of July 28 to be in charge of the Third Court of Control for Terrorism, anticipating that there he would be of greater use to the Maduro cause.

As soon as he set foot in the terrorism court, Betancourt began to act quickly and with a certain perfidy; but, at the same time, he had to abandon his relative anonymity. At least one complaint in the media has already recently exposed him to the public: a citizen, Enma Mendoza, told reporters from the El Pitazo website that her brother, Pedro Antonio Mendoza, had been the target of an express indictment issued from Caracas by Betancourt, who assigned him a public defender and ordered him to be held in prison at the police headquarters of the state of Portuguesa, in the Western Plains of Venezuela, while his eventual transfer to trial is resolved.

The suspect, Pedro Antonio Mendoza, a bricklayer’s assistant, was arrested in Guanare, the capital of the province, on the evening of July 29. A group of people protesting against the results of the presidential election announced the previous morning by the National Electoral Council (CNE), toppled a statue of Coromoto, the local aboriginal chief before whom, according to tradition, the Virgin, the current patron saint of Venezuela, appeared in 1652. Police forces arrested several protesters and occasional passersby in the incident; Pedro Antonio, according to the family, was one of the latter.

A sheriff with guts

Until last year, very little was known about Franklin Mejías Caldera, the 4th Control Judge with Jurisdiction in Terrorism, but some sources indicate that, at just 38 years old, he reached that level thanks to the sponsorship and tutelage of Katherine Haringhton.

The memory of Mejías that remains in the halls of the Palace of Justice in Caracas corresponds more to the time when he worked as a bailiff, the official in the courts who is responsible for receiving and distributing documents. He was also a secretary, until he became a judge.

Mejías Caldera replaced the previous head of the 4th Terrorism Court, José Macsimino Márquez, who was recognized until then as one of the harshest judges of Chavismo. Among other cases, Márquez handed down the sentences of the leader of the Voluntad Popular party, Freddy Guevara, as well as the journalist and political activist, Roland Carreño. He was the executor of the harshest measures against the political prisoner Carla Da Silva, linked to Operation Gedeón , and ordered the extension of the detention of 12 Pemón indigenous people involved in attacks on two military bases in the state of Bolívar in 2019; one of these, Salvador Franco, would die due to lack of medical attention. Despite so many favors for the regime, Macsimino Márquez was arrested in March 2023 by the National Police against Corruption as part of an anti-corruption operation ordered by Maduro.

In line with these standards, Márquez’s successor in the court, Franklin Mejía, handled two cases with a lot of political resonance in 2023: that of student John Álvarez, a member of the Bandera Roja party, and that of Roberto Abdul, president of the Súmate organization, founded by María Corina Machado.

John Álvarez, an Anthropology student at the Central University of Venezuela (UCV), was arrested on August 30, 2023 by officers of the Bolivarian National Police (PNB), who kept him forcibly disappeared for at least 24 hours. Álvarez was linked to the case of six trade unionists from Guayana sentenced to 16 years in prison for leading a public employee protest against the further downward salary adjustment imposed after the application of a new salary scale dictated by the National Budget Office. Those protests were described as “subversive” and “part of a conspiracy” by the Prosecutor’s Office.

Joel García, Álvarez’s lawyer, reported at that time that his client was tortured with electric shocks and beatings, and subjected to threats with a firearm in order to incriminate himself. The accusation against Álvarez was based on the account of an anonymous informant presented by the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Tarek William Saab, the prosecutor appointed by the invalid Constituent Assembly of 2018. That statement was admitted without objections by Judge Mejías, who considered the information from a cooperating patriot to be appropriate , as the newspeak of Chavismo calls its snitches.

On that basis, the 24-year-old was brought to trial and sentenced to 16 years in prison. However, Álvarez would spend only four months in jail. On December 24, 2023, he was released from captivity as part of the prisoner exchange agreed between Washington and Caracas that also benefited Alex Saab , Maduro’s favorite supplier, who until then had been waiting a little over two years in a Miami prison for a trial.

For his part, the president of the civil association Súmate, Roberto Abdul, was arrested on December 6, 2023, and was forcibly disappeared for more than 48 hours. At that time, the director of the Venezuelan Penal Forum organization, Alfredo Romero , announced that Abdul had been presented in a “secret” hearing before the 4th Control Court with Jurisdiction over Terrorism, of Judge Franklin Mejías, which took place at the facilities of El Helicoide, the 1950s building in southwest Caracas that the political police turned into its headquarters and center of detention and torture. There he was accused of treason, conspiracy, money laundering, and criminal association.

Abdul was released on December 20, 2023 , also as part of the group of political prisoners released following the agreement between the United States and Venezuela.

At the time of going to press, rumors were circulating that Mejías had been suddenly removed from his post. The lawyer and former prosecutor, Zair Mundaray, who on August 23 echoed these versions on his account on the X network , formerly Twitter, told Armando.info reporters that he did not know the reasons for the possible dismissal.

No consideration for minors

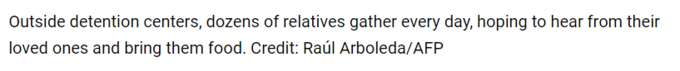

With a few exceptions, relatives of those arrested in the context of the protests following the electoral fraud speak very little to the press. Fear of uncertainty, as well as the absolute discretion that judges in the terrorism courts exercise over the fate of their relatives, has created an almost impenetrable halo of silence. Even more so when the detainees are minors.

Despite these obstacles, for this story it was possible to confirm the existence of a hitherto unknown Court for the Control of Criminal Responsibility of Adolescents in Matters of Terrorism, headed by Judge Joel Abraham Monjes, 58 years old and with a long career within the Judiciary in roles of prosecutor, deputy prosecutor and public defender, always related to the criminal area and common crimes.

Unlike the other judges appointed to prosecute terrorist offences, Monjes has not yet scored any points in his favour for handling a major case. In fact, people who know him and confirm his appointment to that instance, when speaking to Armando.info , expressed surprise that Monjes has accepted such an “ungrateful task”.

“ In the prosecutor’s office, he always acted in accordance with rights and guarantees. He was not known to have committed any acts of corruption or anything similar,” said a colleague who knows his career. Another went even further: “He was a highly appreciated public defender (...) I cannot understand what he is doing there. He is neither ignorant, nor do I consider him a bad person. Nor do I consider him a Chavista.”

Despite these mitigating testimonies, the mother of a detained minor confirms that Monjes has had no problem in adopting the pattern of criminalizing protest. He does not allow the accused to appoint their own defense attorneys and lets them see their relatives only twice a week. The straw that broke the camel’s back for the parents is that Monjes’ office declared a "judicial recess" until September 15, even though the criminal courts do not have such a prerogative.

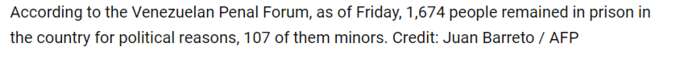

While time is running out for all political prisoners, the Nicolás Maduro regime seems to have lessened, but not ceased, the repressive drive with which it seeks to terrorize and demobilize the protests against it. As of the closing of this edition, the organization Foro Penal Venezolano has identified a total of 1,674 (107 adolescents) detained during the last month and who fit into the category of political prisoners. “The highest number of political prisoners known in Venezuela, at least in the 21st century,” the organization stated in a message on its X account .

Of these, an uncertain number, but surely the majority, is waiting in line to be prosecuted by the judicial terror machine that Nicolás Maduro’s regime has set in motion.

Source: Armando.info

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus