Bird fossil named after Attenborough pushes back history of toothless birds

A newly-discovered fossil named after Sir David Attenborough has pushed back the history of toothless birds by 50 million years.

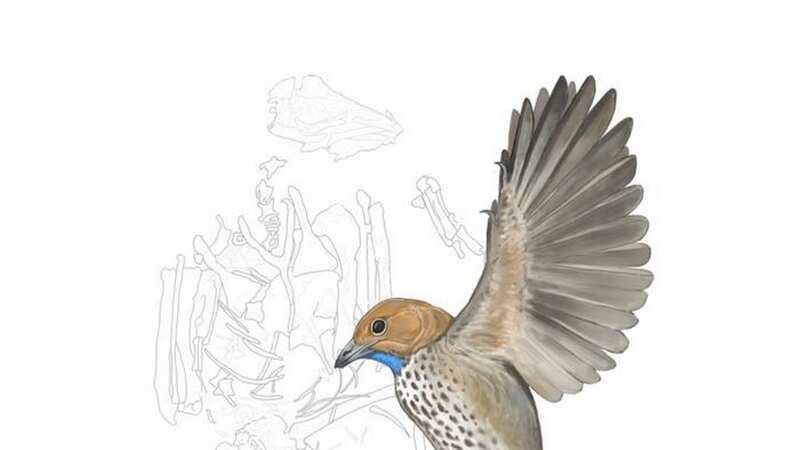

All birds today are toothless but that wasn't always the case and the new bird that lived around 120 million years ago was the first to evolve without teeth. Scientists at the Field Museum in Chicago have named it Imparavis attenboroughi, meaning 'Attenborough's strange bird' in honour of the world-famous naturalist.

Sir David said: "It is a great honour to have one's name attached to a fossil, particularly one as spectacular and important as this. It seems the history of birds is more complex than we knew." Imparavis attenboroughi was a member of a group of birds called enantiornithines, or 'opposite birds', named for a feature in their shoulder joints that is opposite from what's seen in modern birds.

Alex Clark, a doctoral student at the University of Chicago and the Field Museum and the paper's corresponding author said: "Enantiornithines are very weird. Most of them had teeth and still had clawed digits. If you were to go back in time 120 million years in northeastern China and walk around, you might have seen something that looked like a robin or a cardinal but then it would open its mouth, and it would be filled with teeth and it would raise its wing, and you would realise that it had little fingers."

The study published in the journal Cretaceous Research shows that Imparavis attenboroughi was the first of its kind to evolve toothlessness. Enantiornithines were once the most diverse group of birds, but they went extinct 66 million years ago following the meteor impact that killed most of the dinosaurs.

Queen's hilarious joke about Donald Trump after awkward moment at Palace

Queen's hilarious joke about Donald Trump after awkward moment at Palace

Alex Clark, a PhD student at the Field Museum and the University of Chicago (No credit)

Alex Clark, a PhD student at the Field Museum and the University of Chicago (No credit)Scientists are still working to figure out why the enantiornithines went extinct and the ornithuromorphs, the group that gave rise to modern birds, survived. Mr Clark added: "Scientists previously thought that the first record of toothlessness in this group was about 72 million years ago, in the late Cretaceous."

"This little guy, Imparavis, pushes that back by about 48 to 50 million years. So toothlessness, or edentulism, evolved much earlier in this group than we thought." The fossil was found by an amateur collector in northeastern China where it was spotted as a new species by Field Museum associate curator of fossil reptiles Prof Jingmai O'Connor.

She said: "I think what drew me to the specimen wasn't its lack of teeth-- it was its forelimbs. It had a giant bicipital crest-- a bony process jutting out at the top of the upper arm bone, where muscles attach. I'd seen crests like that in Late Cretaceous birds, but not in the Early Cretaceous like this one. That's when I first suspected it might be a new species. We're potentially looking at really strong wing beats."

"Some features of the bones resemble those of modern birds like puffins or murres, which can flap crazy fast, or quails and pheasants, which are stout little birds but produce enough power to launch nearly vertically at a moment's notice when threatened." Mr Clark said based on their findings he believes it acted as a ground forager, saying:"I like to think of these guys kind of acting like modern robins. They can perch in trees just fine, but for the most part, you see them foraging on the ground, hopping around and walking."

Prof O'Connor added: "It seems like most enantiornithines were pretty arboreal, but the differences in the forelimb structure of Imparavis suggests that even though it's still probably lived in the trees, it maybe ventured down to the ground to feed, and that might mean it had a unique diet compared to other enantiornithines, which also might explain why it lost its teeth."

Mr Clark said the name came from his love of watching Sir David Attenborough documentaries as a child. He said: "I most likely wouldn't be in the natural sciences if it weren't for David Attenborough's documentaries. The biggest crisis humanity is facing is the sixth mass extinction, and paleontology provides the only evidence we have for how organisms respond to environmental changes and how animals respond to the stress of other organisms going extinct."

Read more similar news:

Comments:

comments powered by Disqus