A global financial hub boasting one of the world’s most recognizable skylines.

Political stability and investment in trade infrastructure set the stage for the transformation.

But the key was a set of policies that enticed foreigners from around the globe, including laws that made it easy for them to purchase real estate and the creation of free-trade zones with major tax exemptions.

Construction booms ensued, with skyscrapers reaching record heights and mega-projects proliferating, from man-made islands to one of the world’s longest indoor ski slopes. Today, Dubai’s property market is one of the world’s hottest, and foreigners make up more than 90% of the population.

But behind the glittering facade is another factor that aided the city’s rise:

Dubai’s high-rises and villas have served as a safe haven for some of the world’s most wanted criminals, due in part to the secrecy its real estate sector affords.

The city’s property records are difficult to obtain and cannot be easily searched. In some cases, even international law enforcement officials have been unaware that people in their sights owned property in Dubai, one of seven emirates that make up the United Arab Emirates. But thanks to a new leak of data, reporters have identified scores of alleged criminals, individuals facing sanctions, and political figures accused of corruption who have owned property there.

Take, for example, the iconic palm-shaped artificial archipelago known as Palm Jumeirah, where we found an apartment belonging to…

Obaid Khanani,a Pakistani national who, along with his father, was sanctioned by the U.S. in 2016 for allegedly running a money laundering organization that has moved billions of dollars across the globe on behalf of drug traffickers and organized crime groups. He did not respond to requests to comment.

Then over in the nearby Palm Tower Dubai is an apartment owned by Danilo Vunjao Santana Gouveia, a Brazilian businessman better known as “Dubaiano,” who was indicted in 2018 on charges including money laundering and fraud for allegedly running a massive Bitcoin pyramid scheme. Since moving to Dubai, he has taken up a new career in the city as a musician, which he details on an Instagram account alongside photographs of him posing in front of various locations in the city, including the sail-shaped Burj Al Arab Jumeirah skyscraper. His case in Brazil is ongoing. He did not respond to requests to comment.

And in the Grandeur Residences is Joseph Johannes Leijdekkers, a.k.a. Bolle Jos (“Chubby Jos”), alleged by Dutch authorities to be a major player in the global cocaine trade. He did not respond to requests to comment.

A short trip over to the Jumeirah Bay Tower-X3 is an apartment belonging to Daniel Kinahan, an alleged leader of the Kinahan Organized Crime Group, a major Irish drug trafficking cartel that also has a presence in Spain, the U.K., and the UAE, according to U.S. authorities. The U.S. has offered up to $5 million for information that could lead to his arrest. He did not respond to requests to comment.

Heading across town to the Avanti Tower, we find Salam Shebani. Formerly one of Europe’s Most Wanted, currently serving a life sentence in Sweden for money laundering and inciting two murders. He was initially under investigation for receiving fraudulent money into a Dubai account. While Swedish authorities were investigating, Shebani ordered two murders in Sweden, and a 16-year-old was accidentally killed in the crossfire. He still owns his Dubai apartment and records show he rents it out. He did not respond to requests to comment.

At Ridge Towers (Near the Burj Khalifa), we find Vinod Adani, an Indian billionaire facing allegations of stock market manipulation and money laundering across India as a senior member of the Adani Group conglomerate. The allegations, which the Adani Group has denied, and which law enforcement has not pursued, were leveled in January 2023 by a New York-based short seller. Vinod Adani did not respond to a request for comment.

And Othman El Ballouti, wanted in Belgium for allegedly running one of Europe’s top cocaine trafficking networks. He was sanctioned in 2023 by the U.S., where authorities allege his money laundering and narcotics supply chain networks are linked to businesses based in China, as well as South American cocaine suppliers. He did not respond to requests to comment.

Then finally, the Burj Khalifa, Dubai’s iconic skyscraper and the tallest man-made structure ever built.

Here, reporters found two dubious figures from different corners of the world — linked to the same apartment.

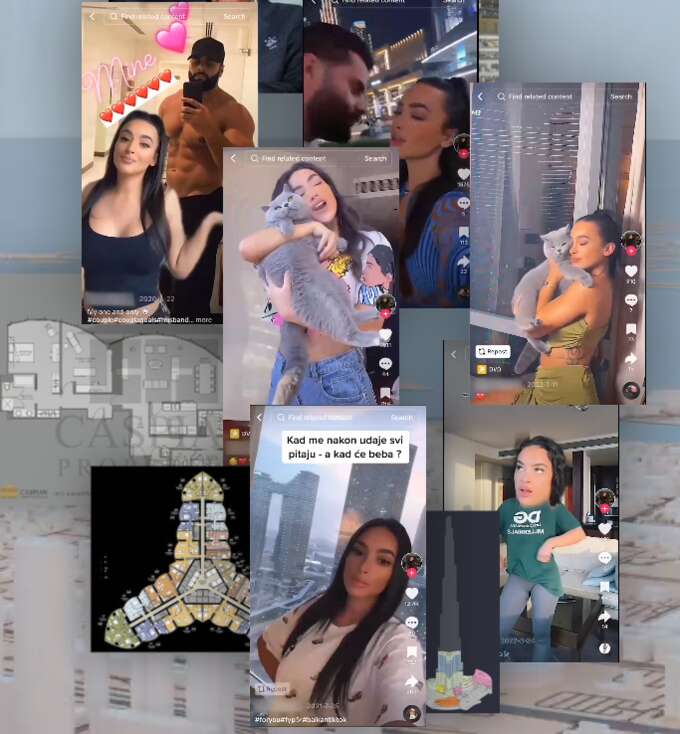

Thanks to these videos posted on TikTok by the wife of Dženis Kadrić, who Bosnian authorities suspect belongs to a major drug cartel, geolocation specialists from investigative outlet Bellingcat were able to pinpoint which apartment the couple lived in.

Kadrić, it turns out, was renting the apartment from another target of law enforcement: Candido Nsue Okomo, the former head of Equatorial Guinea’s scandal-plagued national oil company.

Okomo, who is also the brother-in-law of the country’s controversial president, is under investigation in Spain for embezzlement and money laundering.

A 2023 rental contract confirms the arrangement. Neither Okomo nor Kadrić responded to requests for comment.

Okomo, a former Minister of Youth and Sports, is the brother-in-law of long-term President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, whose family is accused by French prosecutors of looting the African country’s public resources, which are heavily reliant on oil revenues.

Kadrić, a former policeman, was arrested in Bosnia in February on suspicion of participation in organized crime, drug smuggling, and money laundering. He was released in May but remains a suspect in an ongoing investigation. Images on social media show Kadrić in Dubai alongside Bosnian-Dutch citizen Edin Gačanin, the alleged leader of the drug cartel, who was convicted in late 2023 of drug trafficking offenses and sentenced to seven years in prison.

THE DATA

Thanks to the leaked property data, reporters have uncovered dozens of other convicted criminals, fugitives, and sanctioned individuals who have owned at least one piece of real estate in Dubai. There are also political figures and their associates, including those accused of corruption or who have kept their properties hidden from the public.

The leaked records, which date largely from 2022 and 2020, were initially obtained by the Center for Advanced Defense Studies, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit that researches international crime and conflict. The data was then shared with the Norwegian financial outlet E24 and OCCRP, who coordinated an investigative project with more than 70 media outlets around the globe.

Journalists spent months confirming the identity of owners in the data using open source research, official records, previous leaks, and other forms of reporting. Only those individuals whose identities could be verified and who are considered in the public interest — either because of their alleged criminal pasts or political prominence — have been included in this project.

The new data builds on earlier leaks of Dubai property records from 2016 and 2020, providing a more up-to-date look at who owns what across the city’s skyscrapers and opulent villa communities. From alleged Australian cocaine traffickers to the relatives of African dictators and a coterie of sanctioned Hezbollah financiers, the findings reveal how the city has opened its arms to disreputable characters from around the globe.

UAE officials — including at the ministries of interior, economy, and justice — and Dubai Police did not respond to detailed questions, but the country’s embassies in the U.K. and Norway sent a brief response to reporters, saying that the country “takes its role in protecting the integrity of the global financial system extremely seriously.”

“In its continuing pursuit of global criminals, the UAE works closely with international partners to disrupt and deter all forms of illicit finance,” the statement added. “The UAE is committed to continuing these efforts and actions more than ever today and over the longer term.”

Reporters sifted through the leaked data to identify owners whose properties we believe to be in the public interest to reveal.

We separated the owners into categories: convicted and alleged criminals, political figures, and people under sanctions.

The data revealed that these people came from all corners of the globe.

But they had one thing in common: property in Dubai.

WHY DUBAI?

Dubai is far from the only place where criminals and others looking to stash their wealth have been able to scoop up properties — New York City and London real estate have also been known to attract dirty money.

But experts interviewed by OCCRP said there are several factors that strengthen Dubai’s appeal, particularly for those who are thwarted by sanctions from owning property in Western democracies, or are on the run from law enforcement.

One pull factor, experts say, has been the emirate’s inconsistent responses to requests from foreign authorities for help arresting and extraditing fugitives.

Despite the city’s reputation for heavy surveillance, a number of alleged drug traffickers and other criminals have sought refuge there over the past decade.

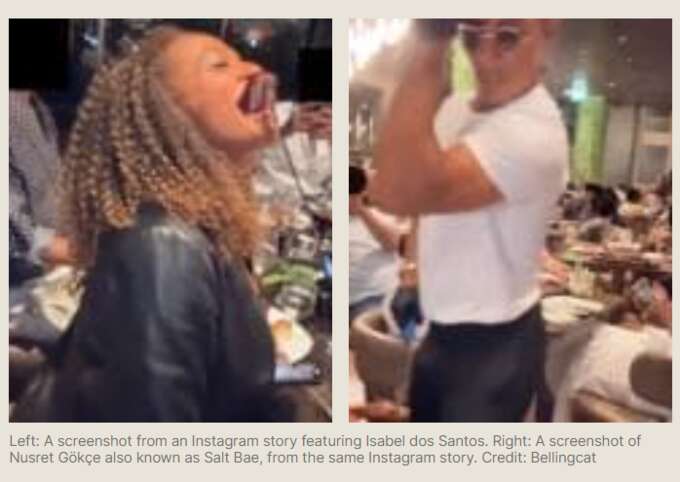

Others, such as Isabel Dos Santos, the ultra-wealthy daughter of Angola’s longtime dictator — who has been charged in Angola with money laundering, embezzlement, and tax fraud, had her properties frozen in several countries, and is barred from entering the U.S. — not only own property in Dubai but have been openly seen enjoying the city’s luxuries.

When reached for comment, Dos Santos said she had purchased the Dubai property with income from her private sector businesses, and accused Angolan authorities of a politically-motivated agenda.

While the country has recently signed a raft of extradition treaties and UAE police say they have extradited hundreds of wanted criminals, experts say the process is political.

According to Radha Stirling, an attorney and human rights advocate who leads the legal assistance organization Detained in Dubai, UAE authorities use high-profile fugitives as “bargaining chips.”

“The presence of extradition agreements between nations are not necessarily key to whether or not people are extradited,” she said.

“What matters is what Dubai wants in return and whether that nation has something they want enough to barter.”

When asked about the country’s record on extraditions, Sauod Abdulaziz Almutawa, an officer from Dubai police’s anti-money laundering department, stressed the recent arrests of those with red notices and said that extradition requests, which must pass through local courts, take longer to process and often face challenges from deep-pocketed defense teams.

“What matters is what Dubai wants in return and whether that nation has something they want enough to barter.”

“We are increasing our capacity, increasing and developing our resources.. to meet the expectations of our foreign counterparts,” he told Swedish broadcaster SVT in a March interview.

Jodi Vittori, a professor at Georgetown University who studies corruption and illicit finance, described the inner workings of the authoritarian country’s justice system as opaque.

“It is unclear why the UAE will work with some law enforcement in some cases to arrest criminals located in the UAE and in other cases, they do not,” she told OCCRP. “In many ways, the UAE is a law enforcement black hole.”

She cited the India-born Gupta brothers, who are accused of looting South Africa’s public funds through their close links with the country’s former President Jacob Zuma, as a recent example.

President Jacob Zuma and Atul Gupta at a breakfast in Port Elizabeth. Photo source: South African Government.

Despite an extradition treaty between the two nations, last year the UAE quietly dismissed South Africa’s request to extradite Atul and Rajesh Gupta, who face charges of money laundering and fraud.

The move shocked South Africa, where authorities have said the UAE failed to provide “satisfactory responses” on the reasons behind the rejection.

A UAE official did not reply to specific questions about the Guptas, but said it “works closely with international partners to disrupt and deter all forms of illicit finance.” The Guptas and Zuma did not respond to requests for comment.

‘BAGS OF CASH’

In addition to its vast offerings of high-end real estate, Dubai holds another allure for those with ill-gotten cash to spend: the reputation among some of the city’s realtors for a few-questions-asked approach when it comes to the origins of investors’ funds.

Between their status as politically-exposed persons (PEPs) or appearance on sanctions lists, the dozens of individuals found by OCCRP should have immediately raised red flags under any basic risk assessment.

John Christensen, whose U.K.-based organization the Tax Justice Network ranks the UAE as eighth in the world in terms of financial secrecy, described Dubai as host to “a range of professional enablers.”

There are “lawyers, bankers and real estate practitioners who flout international requirements to report on suspicious transactions, and know the origins of the wealth of the clients they are serving,” he told OCCRP.

Emirati authorities have tightened regulations in recent years, particularly since the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an inter-governmental anti-money laundering watchdog, placed the country on a “gray list” for its failures to effectively combat illicit money flows in 2022. After reportedly lobbying hard to get off the list, Emirati authorities were rewarded with good news in February: FATF welcomed “significant progress” and cleared the UAE from the extra monitoring.

But some experts have warned that the move was premature.

“Recent reforms to the penal code and judiciary might have sufficed to get Dubai lifted from FATF’s gray list this winter, but they haven’t substantively shifted the nature of the real estate market,” said Colin Powers, a senior fellow and chief editor for the Noria MENA Program, an independent non-profit research organization.

The reforms do not “change what makes the real estate market so attractive for storing wealth,” he added, citing buyers’ ability to disguise their ownership behind trusts, holding companies, and foundations.

According to a statement from UAE anti-money laundering authorities earlier this year, real estate agents, brokers, and corporate service providers have stepped up reporting of suspicious transactions since 2022, while the total value of fines imposed by regulators has increased threefold.

But figures provided by a December 2023 government report show that the suspicious transaction reports filed by realtors and brokers between the second half of 2020 and the first half of 2023 would have only accounted for .002 percent of the total real estate transactions from the year 2022 alone. The current reporting regulations also only apply to property sales, leaving rental activities in the shadows.

In an undercover consultation in March with a salesperson from the leading Dubai real estate development firm Damac, SVT reporters were told they could pay in “bags of cash” or cryptocurrency to purchase a flat, and that they would face “zero question(s)” about their funds.

“In properties you are not going to be questioned from any department…especially the developer himself. Anyone who wants to buy can buy,” the realtor assured them.

He also described how pouring cash into real estate is one way to avoid questions from banks about the source of their funds.

“There are people, they have cash… and they don’t know where to put it. They cannot put like 100 million dirhams ($27.2 million) in the bank. There will be hundreds of questions,” he explained.

But, “if you sell the property and then you transfer all the amount in the bank account, then there is no problem, you will not be questioned from where you bring the cash to buy the property and then to put it in the bank,” he said.

“You still have this option in Dubai. So why not use it?”

When reached for comment, Damac said the firm runs due diligence checks on all its clients, and that it is not the company’s policy to recommend customers buy in cash.

“Had your undercover reporter proceeded further through the sales process beyond the mere first encounter with a salesperson, they would have witnessed the scrutiny and the heightened measures we apply to transactions that trigger red flags,” the agency said, adding that it would investigate the salesperson’s statements.

When told about the incident, the officer from Dubai police’s anti-money laundering police unit, Sauod Abdulaziz Almutawa, said the emirate has a “zero risk tolerance to noncompliance” and that actions are taken against those who turn a “blind eye” to the law.

“Dubai is not a safe haven for illicit funds for illicit actors. Dubai is a safe haven for legitimate commerce, for legitimate individuals who are hardworking and have earned what they have otherwise,” he added.

Melissa Sequeira, a customer service manager from Themis, a U.K.- and UAE-based firm that helps clients manage financial crime risks, praised the government’s tougher regulations and said there had been a significant increase in inspections of realtors in recent years. But she noted that change on ground level is a work in progress, particularly among smaller firms with limited resources, in a sector where just a few years ago “you could buy a property with just a passport.”

The goal is to shift the “tone from senior managers, who are more focused on profit rather than stopping the global financial, negative impacts of crime,” she told OCCRP.

In April, a large majority of the European Parliament voted to keep the UAE on the EU’s list of “high-risk third countries” after it had been removed in response to the FATF decision.

"Those who circumvent sanctions against Russia should not be rewarded with removal from the EU list,” MEP Rasmus Andresen told OCCRP, calling for a more thorough review of the country’s anti-money laundering measures before a decision should be made.

With a new war in the Middle East, some suspect that geopolitics is likely to lighten scrutiny on the UAE for the near future.

The U.S. is hoping the UAE and other allies in the Middle East will help with the daunting task of rebuilding Gaza, and routing funding through a country on the FATF gray list could be seen as untenable.

“The UAE’s facilitation of corruption, money laundering, and organized crime undermines larger Western efforts to fight everything from fentanyl to human trafficking to illicit financial flows,” said Vittori, the expert on corruption and illicit finance. “But it will be hard for Western governments to ask the UAE to rebuild Gaza and at the same time put pressure on FATF to put the UAE back on its money laundering gray list or otherwise sanction them.”