Fishing boats and cargo ships: How Colombian cocaine is trafficked worldwide

Official statistics on busts of drug shipments originating in Colombia — the world’s largest cocaine producer by far — are scattershot and hard to find. A leak of prosecutor’s office documents helped reporters fill in some gaps.

Early one summer morning, two small boats sidled up to the Cap San Tainaro, a container ship off the coast of the northern Colombian port city of BarranquillaBarranquilla. A dozen men raised ladders and scaled onto the vessel, and then, using ropes and pulleys, began to hoist up bags with hundreds of plastic packages, each of which contained a kilogram of cocaine.

A military helicopter patrolling the area spotted the men and hailed the ship. After four hours, they finally made contact and guided the vessel back to the dock, where authorities boarded it, found the drugs — over one metric ton in total — and arrested those suspected of involvement

This article is part of the NarcoFiles: The New Criminal Order, an international investigation into modern-day organized crime and those who fight it. The investigation began with a leak of data shared by two organizations, Distributed Denial of Secrets and Enlace Hacktivista. Read more about the project here.

Few details of the bust, which took place on August 2, 2018, were included in the statistics reported by Colombia’s authorities. Instead, reporters uncovered the minute-by-minute account of the operation in a massive leak of documents from the country’s prosecutor’s office, known as the NarcoFiles .

In Colombia, the world’s largest cocaine producer, statistics on drug busts are scattershot and hard to find. At least four different agencies keep records of seizures, but they are not easily accessible to the public and often do not overlap.

Cocaine plantation in Colombia, South America.

When data is published, it typically includes little beyond the date, location, and amount of drugs seized. And Colombian authorities do not keep data on busts of Colombian shipments that take place abroad, making it difficult to understand the full picture of how drugs are smuggled out of the country.

These limitations make it harder for reporters and civil society to analyze trafficking trends. Drawing on the NarcoFiles, OCCRP’s partner, Cuestión Pública, has spent over a year building a database that aims to change that.

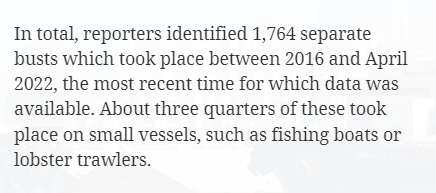

By combing through the leaked files, reporters identified 158 busts of drug shipments that originated in Colombia. They then created a more comprehensive database by contacting Colombia’s defense ministry, prosecutor’s office, navy, and police, and filing freedom of information requests to gain access to their records. The data was also supplemented by reports from Belgium’s Customs Federal Service.

Twenty-two of the busts in the leaked documents did not appear in any official database. In dozens of other cases, the leaked documents supplemented official reporting, allowing reporters to uncover information such as where the seizures took place, as well as the export company, customs agent, importer, and shipping firms involved.

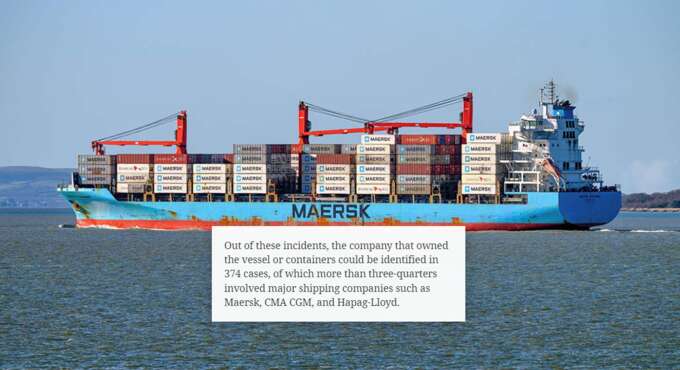

For instance, in one May 2016 operation unreported by Colombian agencies, reporters found that 2.3 metric tons of cocaine left the Colombian port of Santa Marta in four containers owned by the Danish shipping company Maersk before being intercepted in Romania.

In another case, the leak allowed reporters to identify the shipping company and exporter for a March 2022 haul busted in Southampton, in the U.K. The case had been reported by British media but did not show up in any official Colombian databases, even though it had been investigated by prosecutors.

The data still has holes. For instance, in about 13 percent of cases involving large vessels, there was no information about the shipping or container company. In 17 of those cases — four percent — reporters could not see where the drugs were seized. And, of course, the data does not provide insight into the hundreds of tons of cocaine successfully trafficked each year.

Still, the new information allowed reporters to piece together a richer portrait of how Colombian cocaine is smuggled onto commercial container ships than was previously possible. They found:

Boarding Big Ships

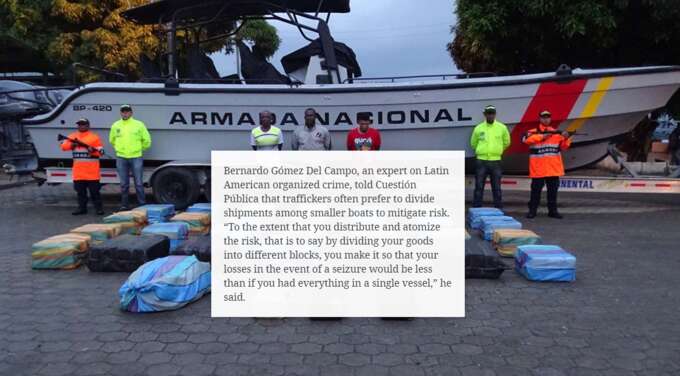

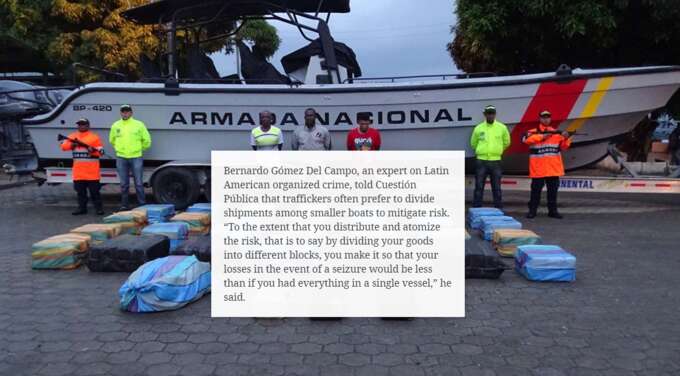

While small boats still appear to be the top choice for smugglers, cocaine traffickers’ use of large container vessels is on the rise, according to the U.N. drug agency’s latest report. And the methods of contamination are becoming increasingly sophisticated, the report notes, creating a major headache for commercial shipping companies.

Last year, the Financial Times reported that an executive at the Danish shipping giant Maersk warned drug gangs were infiltrating entire supply chains, while the international firm MSC saw eight crew members sentenced in the U.S. for conspiracy to smuggle cocaine after one of their ships attempted to sail nearly 20 tons of cocaine through the city of Philadelphia in 2019.

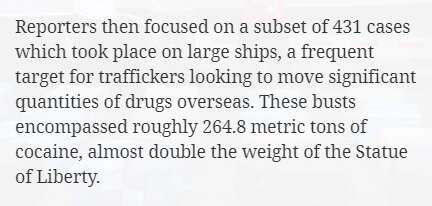

The NarcoFiles data reveals fresh details about how companies such as these are breached — as well as which lines are most frequently targeted.

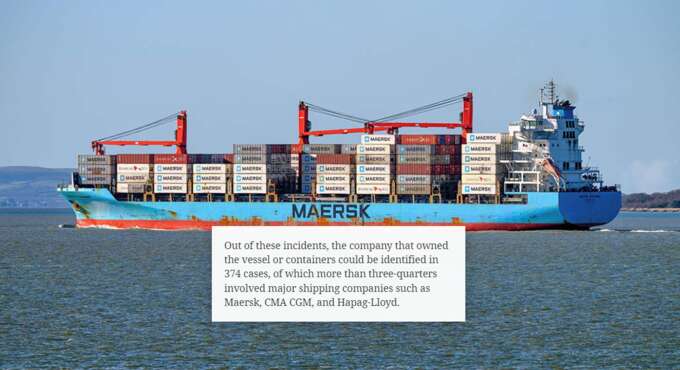

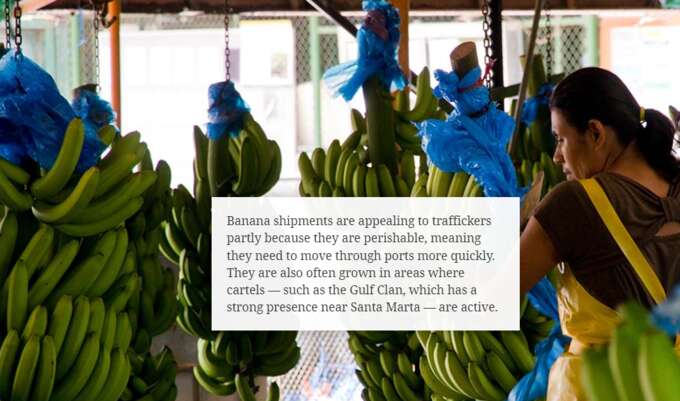

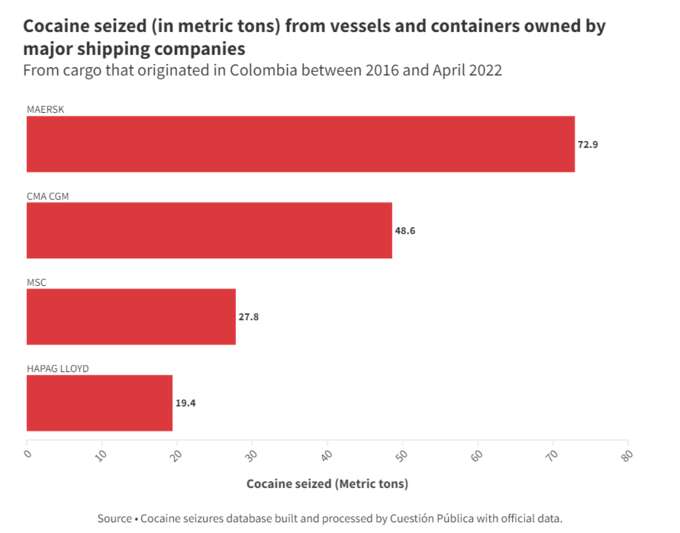

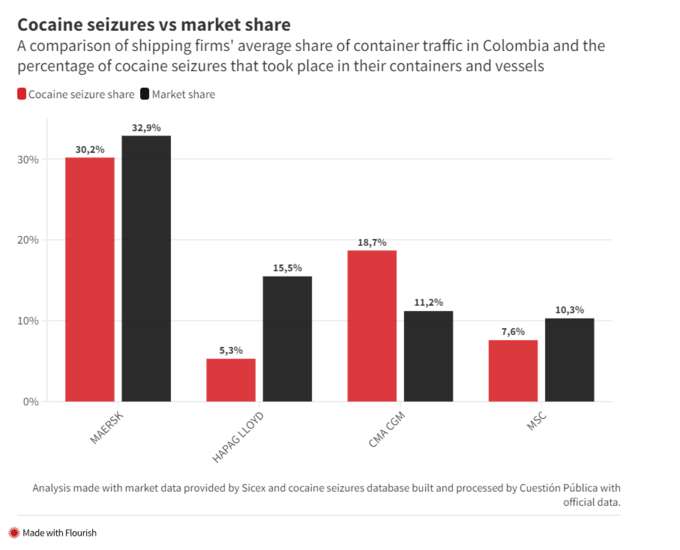

Reporters found that containers and vessels operated by Maersk, which dominates the Colombian market, were involved in the highest number of drug busts in the dataset, accounting for more than a third of the 374 cases where the shipping or container company could be identified. The infiltration of Maersk vessels was on average in proportion with the company’s share of container traffic in Colombian ports, according to a platform that records the quantity of containers each company manages.

When reached for comment, Maersk attributed the seizures to boosted cooperation among governments in Latin America, Europe, and the U.S.

“Their increased efforts, supported and assisted by the shipping and terminal industries, are likely reflected in the seizure amounts of narcotics contraband,” the company said in a statement, adding that it would continue to assist authorities to combat smuggling.

The second highest share of seizures in the data involved the French group CMA CGM, another of the world’s largest container shipping companies. Between 2016 and 2021, the French company managed an average of 11% of Colombia’s container maritime traffic, and accounted for 19% of the seizures that took place on large ships.

In a statement to reporters, the company described the fight against illicit trafficking as a “top priority,” but declined to comment on the specifics, citing the safety of its staff and operations.

“CMA CGM closely collaborates with law enforcement, customs, and judicial authorities in all the countries affected by this type of trafficking, thereby helping to combat it,” the statement said.

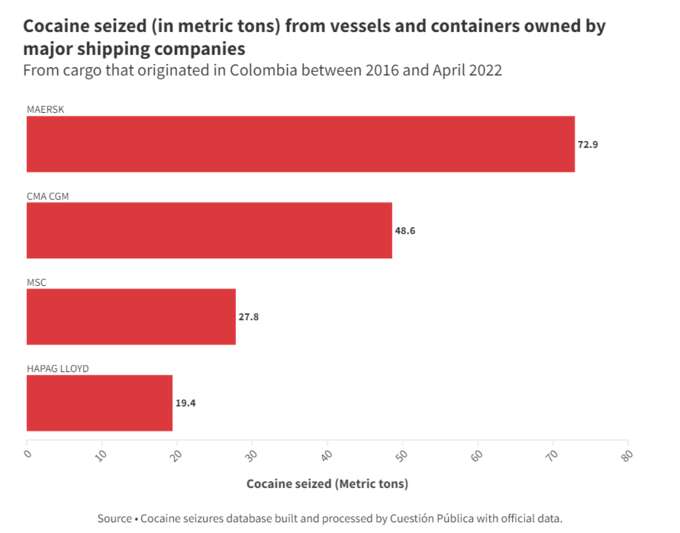

In terms of the volume of narcotics, Maersk shipments were the site of 72.9 metric tons of cocaine seized on large ships, while CMA CGM shipments accounted for about 48.6 metric tons.

Henrik Vigh, an anthropology professor and expert on organized crime and drug trafficking at the University of Copenhagen, said that larger firms such as these might be appealing to traffickers because they offer a door-to-door service.

“Major shipping companies like Maersk are particularly attractive because they don’t just sail with container ships, but offer to handle the entire logistical chain both on land and at sea,” he said. “The fewer times the goods have to change hands, the less is the risk of being checked and discovered.”

Documents found in the NarcoFiles indicated that some traffickers may develop preferences for certain shippers’ services as well.

In 2023, Colombian prosecutors linked several cocaine shipments totaling more than six tons to a criminal structure that operated in the Colombian ports of Buenaventura and Cartagena. According to intercepted phone calls, emails and other evidence gathered by an ongoing Colombian investigation, the organization relied on CMA CGM ships on at least two occasions in 2019 and 2020 with the help of bribed police officers in the ports.

One of the shipments, which was seized in June 2020 in the port of Cartagena, was packed with 2,500 kilograms of cocaine destined for the French port of Le Havre. In an email exchange with the exporter, the importer’s legal representative stated that his client preferred the CMA CGM shipping line.

“[In] principle, my buyer client only accepts CMA as a shipping company because of the conditions of their equipment and for their internal reasons,” read the email, which was cited in a judicial report supplied to Colombian prosecutors.

“I cannot contradict them for the very fact that they are a client that is always right, as the saying goes,” the email continued. “So please we need these shipments to be made through CMA.”

While the importer claimed to be supplying a supermarket chain, the report from Colombian investigators alleged his firm was a shell company formed solely to facilitate the cocaine trafficking.

The company’s legal representative was initially arrested in Spain on drug trafficking charges, but his case was later suspended due to lack of evidence. Colombian prosecutors did not confirm whether he was still under investigation in Colombia.

CMA CGM did not respond to queries about the case.

Anti-narcotics police in Colombia seize a cargo of molasses mixed with cocaine meant to be sent to Spain, in 2022.

Messages showing a preference for certain piers, including those where Maersk operates, were also found in the NarcoFiles.

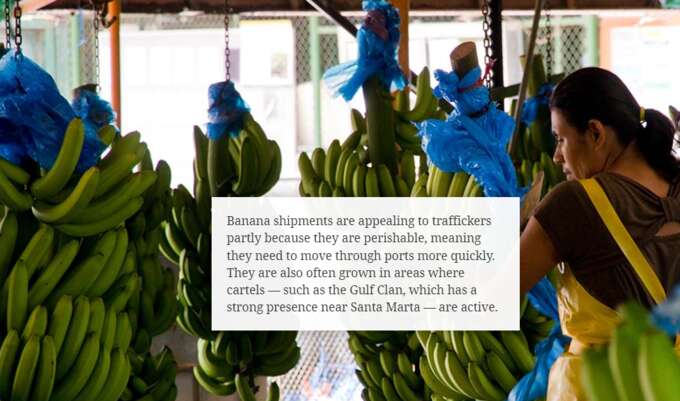

One informant, whose account was recorded by the Colombian prosecutor’s office, said the traffickers he knew of were looking to send their Antwerp-bound shipments “exactly to piers 188 and 234, where containers with bananas from Maersk Line arrive.”

Pier 188, where nearly 1.6 metric tons of cocaine was seized in 2019 alone from two Maersk vessels and one ship operated by Dole, was also referenced in a separate case found in the leaked files. In that investigation, wiretaps carried out in 2021 caught a suspected drug trafficker saying that “everything that goes through Antwerp has to go through MMAU [SP] warehouse 188.” MMAU is a code used by the Bureau of International Containers to identify Maersk-owned containers.

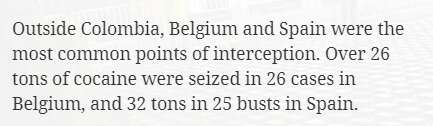

Vigh, the organized crime expert, said the preferences could reflect the benefits of working through fast-paced piers that handle perishable goods.

“In these piers, it is complicated for the authorities to stop the entire flow of containers for several weeks if they suspect smuggling, because then the food rots, and you risk putting a plug in the entire transport chain of containers,” he said.

Major shipping companies have recently pledged to do better to secure their shipments against traffickers. In 2023, MSC, Maersk, CMA CGM, Hapag Lloyd and Seatrade directors signed a “declaration on the fight against cross-border organized drug crime” with the Belgian and Dutch governments. It includes commitments to exchange information and institute better background checks on staff.

But combating the market forces behind the shipping industry will be a challenge, according to experts.

“If you step in and restrict this free movement of goods, you risk very quickly creating supply chain problems,” said Vigh. “If, for example, you start checking ships and containers more intensely or overregulating the ports, you risk slowing down global trade very quickly. That’s why many countries are panicked about touching this.”

Katja Lindskov Jacobsen, an associate professor and expert in maritime security at the University of Copenhagen, added that keeping up with the criminals is another obstacle.

“Even if the control is stepped up and more containers are checked, it will not necessarily be enough to completely eliminate the problem,” she said. “The criminals are often very good at adapting and finding creative countermeasures.”

Begoña P. Ramírez (InfoLibre), Paul Vugts (Het Parool), Lars Bové (De Tijd), Angus Peacock (OCCRP), and Pavla Holcova (Investigace.cz) contributed reporting.

Data from the Colombian Navy was also contributed by Vorágine, while the K-Lab of Fundación Karisma provided additional support, and Peace Brigades International assisted with security concerns.

James Smith