UK wage growth remained strong even as the UK unemployment rate rose to its highest for almost a year.

The jobless rate increased to 4.3% between January and March, the highest since May to July last year, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said.

The number of vacancies also slowed meaning more unemployed people are competing for the same jobs.

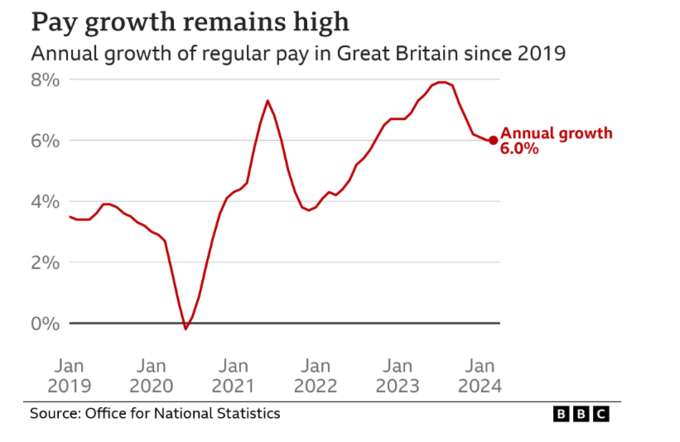

But pay rises, excluding bonuses, remained at 6%. It had been expected to slow to 5.9% between January and March.

Taking inflation - which measures the pace of price rises - into account, wages rose by 2.4%. Liz McKeown, director of economic statistics at the ONS, said that "real pay growth remains at it highest level in well over two years".

But she also said there were others "tentative signs" that the British jobs markets is "cooling".

Jobs on offer in the UK dropped by 26,000 to 898,000 vacancies between February and April. The total remains higher than pre-pandemic levels but Ms McKeown said: "With unemployment also increasing, the number of unemployed people per vacancy has continued to rise, approaching levels seen before the onset of Covid-19."

In the first three months of this year, the number of unemployed people per vacancy rose to 1.6. That compares to 1.4 unemployed people for every vacancy in the comparable period between October and December 2023.

The ONS said: "Although this ratio remains low by historical standards, it does demonstrate a slight easing in the labour market, with vacancies falling alongside rising unemployment."

Meanwhile, those claiming benefits in April rose to 1.5 million, up 29,300 compared to the same month last year.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt said wage rises would "help with the cost of living pressures on families".

He added: "While we are dealing with some challenges in our labour supply, including pandemic impacts, as our reforms on childcare, pensions tax reform and welfare come online I am confident we will start to increase the number of people in work."

But Labour’s acting shadow work and pensions secretary, Alison McGovern, said "these damning new figures prove that things are just getting worse".

She said: "It’s no wonder there are now a record number of people locked out of work due to long-term sickness, given NHS waiting lists are spiralling and the Tories have pushed our NHS to its knees."

The rate of people considered "economically inactive" - defined as those aged between 16 to 64 years old not in work or looking for a job - edged a little lower to 22.1% in the first three months of the year.

The ONS said the increase in economic inactivity in the latest quarter was largely driven by people not be working "because they were temporarily sick, long-term sick or retired".

It has warned, however, that its figures should be treated with a degree of caution because they are based on a smaller sample of household questionnaires than it used to rely on before Covid.

Brigitte Wurfel-Mathurin from Gloucester, gave up her job as a supervisor at a day nursery after her husband was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

She initially tried to keep working at the job she loved but said: "There was no way I could leave him alone all day, but I’d done the maths and I couldn’t afford to pay for his care on my modest salary."

Ms Wurfel-Mathurin said the amount she receives in carers allowance left her feeling "completely undervalued".

"I was sad to give up my job because this is what I loved to do, I was very experienced and had years of training," she said. "But I’m also happy to spend the time while I still can with my husband."

Interest rates

While overall pay growth, excluding bonuses, was unchanged between January and March, it slowed a little to 5.9% for private employers.

The wage figures will be closely watched by the Bank of England to decide if and when interest rates can be cut.

The next rate-setting meeting is in June and there are a number of key economic releases before then which the Bank will use to make its decision. This includes inflation as well as wage figures for April, when an increase in the National Living Wage came into force.

"While the further easing in regular private sector pay in March suggests that wage pressures faded a bit faster than the Bank of England expected, broader measures of wage growth are probably still a bit too strong for the Bank’s liking," said Ashley Webb, UK economist at Capital Economics.

"At the margin, this may make the Bank a bit more uneasy about first cutting interest rates in June."

At its most recent meeting, Bank governor Andrew Bailey said he was "optimistic that things are moving in the right direction", though he added that a fall in borrowing costs was "not a fait accompli".

Rates have been 5.25% since last August, the highest level in 16 years.