A breakthrough new study using NASA's MESSENGER probe hints aliens could live below Mercury's north pole.

Scientists believe that area of the planet might have the right conditions to support some "extreme forms of life" despite how close it is to the searing heat of the Sun. The Planetary Research Institute investigation says life forms could live within glaciers of salt under the surface of Mercury, as they are packed with volatile compounds.

Similar conditions exist on parts of the Earth. Lead author Dr Alexis Rodriguez said: "This line of thinking leads us to ponder the possibility of subsurface areas on Mercury that might be more hospitable than its harsh surface."

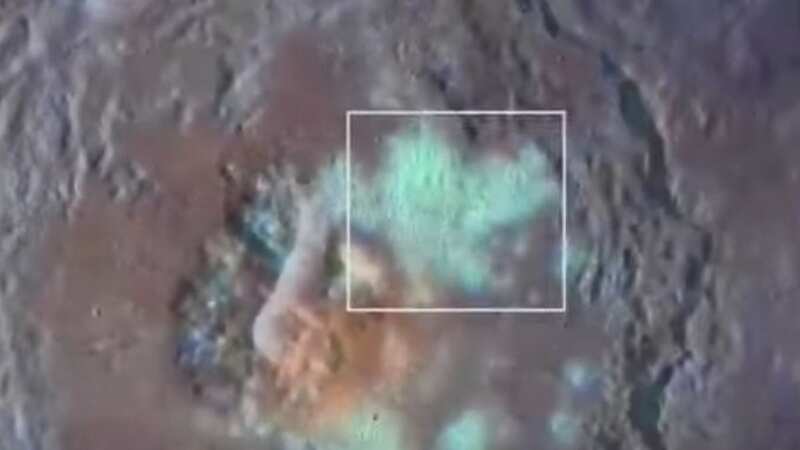

The NASA probe was used to examine the geology of Mercury's north pole. And using that data the team discovered evidence that salt might flow through its Raditladi and Eminescu craters. Unlike the Earth's ice glaciers, those on Mercury are composed of salt, trapping water, nitrogen and carbon dioxide.

When the planet - which sits closest to the Sun - was struck by space rocks, the resultant craters smashed through the outer layer of basalt rock and allowed for such volatile compounds to flow, forming the glaciers. The average daytime temperature on Mercury is around 430C, so such chemicals have now evaporated.

'Weird' comet heading towards the sun could be from another solar system

'Weird' comet heading towards the sun could be from another solar system

But the research team were able to estimate where the craters had been by comparing features on Mercury to those on Earth. Dr Rodriguez said: "Our models strongly affirm that salt flow likely produced these glaciers and that after their emplacement they retained volatiles for over 1 billion years."

Mercury is the smallest planet in the Solar System and sits closest to the Sun (Getty Images/Science Photo Library RF)

Mercury is the smallest planet in the Solar System and sits closest to the Sun (Getty Images/Science Photo Library RF)The layer of salt under the planet's surface is in theory hidden from the Sun's heat but has trapped the volatile compounds that could support life forms because similar habitats exist on Earth.

Dr Rodriguez said: "Specific salt compounds on Earth create habitable niches even in some of the harshest environments where they occur, such as the arid Atacama Desert in Chile."

Prior to this discovery, experts believed Mercury to be uninhabitable due to the major heat fluctuations, lack of atmosphere and constant solar radiation. But like the Earth's 'Goldilocks zone' - which sits at the right distance from the Sun to allow for life to thrive, the scientists think that beneath Mercury's surface is something similar.

Dr Rodriguez added: "This groundbreaking discovery of Mercurian glaciers extends our comprehension of the environmental parameters that could sustain life, adding a vital dimension to our exploration of astrobiology also relevant to the potential habitability of Mercury-like exoplanets."

Mercury is the smallest planet in the Solar System, with an equatorial radius of 2,439.7 kilometres (1,516.0 miles). The intensity of sunlight on its surface is between 4.59 and 10.61 times the Sun's typical energy received by the Earth.