With government complacency, agricultural production companies with million-dollar profits use second-hand vehicles, or vehicles with expired permits, to transport their laborers to the work camps in Jalisco. The result: death, pain and impunity.

Companies take advantage of little or no official supervision to leave injured people to their fate and not pay compensation to victims’ families.

Tobisai Domínguez Gasga sensed it from the moment he noticed that the brakes failed: he would not survive.

“Hold on, everyone, it’s not holding the brake!” shouted Arturo Hernández de los Santos, the driver of the bus that was transporting 33 day laborers, workers of the BerryMex company.

Traveling with Abisai was his friend Froilán Alameda Carrera, who remembers that he was unable to hear the warning clearly; He only saw and heard his companions scream in despair. He did not know what was happening, but fear invaded him when he perceived the speed at which they were descending.

They were going in a nosedive, in the middle of the curves of highway 405 Tuxcueca-Mazamitla in the southeast of Jalisco, very close to Michoacán, which they should travel at low speed, but the truck was already exceeding 90 kilometers per hour, and soon exceeded 100 .

Abisai smelled death before the out-of-control vehicle crashed. Then he said to Froilán: “Well, it’s up to us, right?”

“My partner said goodbye to me,” he says.

As they exited the curves, something thundered; a roar was heard.

People were shouting, banging on the windows, fighting and pulling to remove the frame, throwing their arms out trying to get out. There were no options: if they were thrown from the bus at that speed, the impact of the fall could kill them.

The driver managed to direct the unit marked with the number 363 in the opposite direction, towards a deviation at the intersection that connects the Tuxcueca-Mazamitla highway, with the 446 Citala-Tuxcueca, to take a slope. On the way up he tried to get the force of gravity to stop the vehicle. As best he could, he avoided trailers and cars that he encountered in front of him. He could not avoid the metal retaining fence. He was shocked twice.

Like a ping-pong ball, without control, the truck bounced until it collided with a stone hill on the first curve.

Pieces of the chassis burst, the seats flew off and were left on the side of the road. Nothing remained of the front; just an amorphous mass.

In the first crashes, Froilán lost consciousness; He woke up when everything had happened.

Somehow, he survived, but that fateful May 18, 2022, his son Frank Irving, his sister-in-law Ariadna Ortiz Cortés, his friend Abisai and eleven other people did not.

Arturo, the driver who tried to save them all with his maneuvers, died hours later in the hospital. He was a 25-year-old young man, originally from Mezcala, a town in Jalisco on the shores of Lake Chapala. He had been at Grupo Ruza for just three months, the transport company hired by the export company BerryMex, a subsidiary of the transnational Reiter Affiliated Companies (RAC).

Trips to the fields

Every day, in Jalisco, thousands of day laborers make trips in death trucks like the one Abisai, Froilán, their family, and the gang they were part of made. At 5:30 in the morning a bus picked them up at the BerryMex shelters in Jocotepec and, approximately two hours later, they parked in the fields of Mazamitla.

That May 18th it was their turn to harvest blackberries.

When they arrived at the greenhouses, they put on gloves to protect themselves from the plant’s thorns, took buckets, hung them around their waists, got between the rows of crops and plucked the delicate fruits, which they placed in the containers. On their return they emptied them into containers. They will then be packaged in clamshell , those transparent plastic baskets that the buyer sees in the supermarket.

In Mexico there are 55,400 hectares of berry greenhouses (as strawberries are known: strawberries, raspberries, blackberries and blueberries), and for that size of crop - according to the Agricultural Marketing Service of the United States Department of Agriculture ( USDA Market, for its acronym in English) — 443 thousand workers are needed.

Jalisco, self-named by its rulers as the “Agri-Food Giant”, concentrates 16% of national production, only surpassed by Michoacán.

Almost the entire harvest is sent to the United States. In 2022, according to the same source, Mexico sent 401 thousand tons of blueberries, 169 thousand tons of raspberries, and 1.17 million strawberries. A third of the exports are in charge of the RAC conglomerate, says Miguel Ángel Curiel Mendoza, director of Driscoll’s in Mexico, interviewed for this investigation. RAC has several subsidiaries, one is Driscoll’s, which exports the products of the BerryMex company that Abisai, Froilán and other day laborers harvested.

To meet that production level, daily work ends between 6 and 7 p.m. Twelve hours after arriving at the nurseries, after a day in the sun, they take the truck back to the shelters.

According to data from the International Trade Center ( ITC ), the value of exports of these red fruits for Mexico worldwide was 1,719 million dollars in 2022; Of this total, 1,661 million dollars came from the US market.

For this work, day laborers like Froilán and Abisai receive around 231 pesos a day.

The road on which bus 363 crashed begins in Mazamitla, within the Sierra del Tigre. The route of more than 70 kilometers begins in a forest with a refreshing pine aroma. From the vehicle windows you can see the black nylons and white tunnels of the berry greenhouses —also called ranches—which form a canvas of plastics that, polished by the reflection of the sun, dazzles the eye.

Little by little, the forest and the pines are left behind. Beyond the window there is a view reminiscent of the jungle, but as the road progresses, the wooded hills turn into vacant land. The temperature begins to rise and, when least expected, the imposing Lake of Chapala appears. The greenhouses have spread so much that they have even taken over the riverbank.

To make that trip daily, all the components of the vehicle have to function correctly. There should be no margin for error. This is required by a road full of curves, with straight, inclined sections.

The brakes are a key piece. That afternoon, those on the Ruza Empresas bus failed.

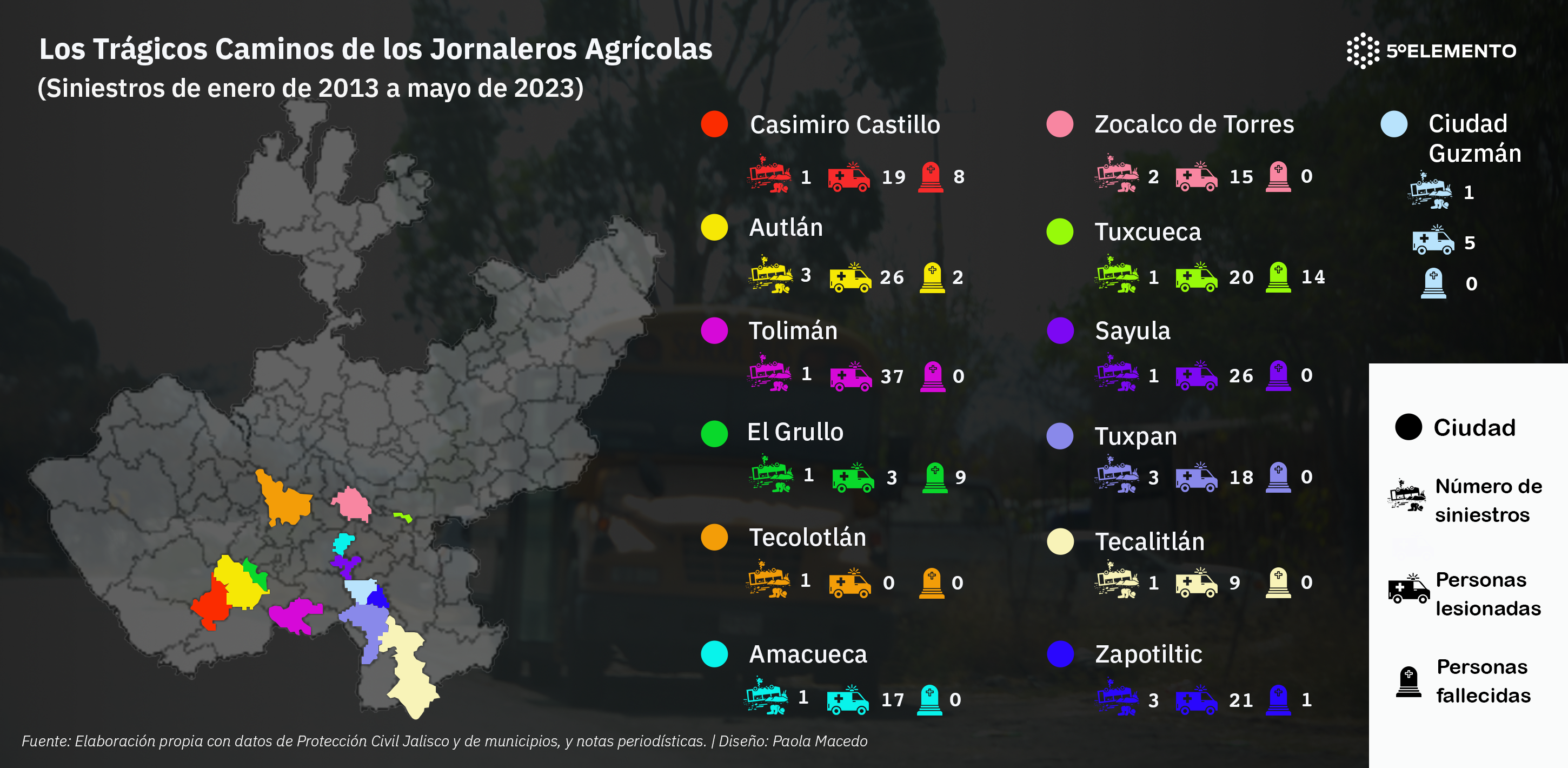

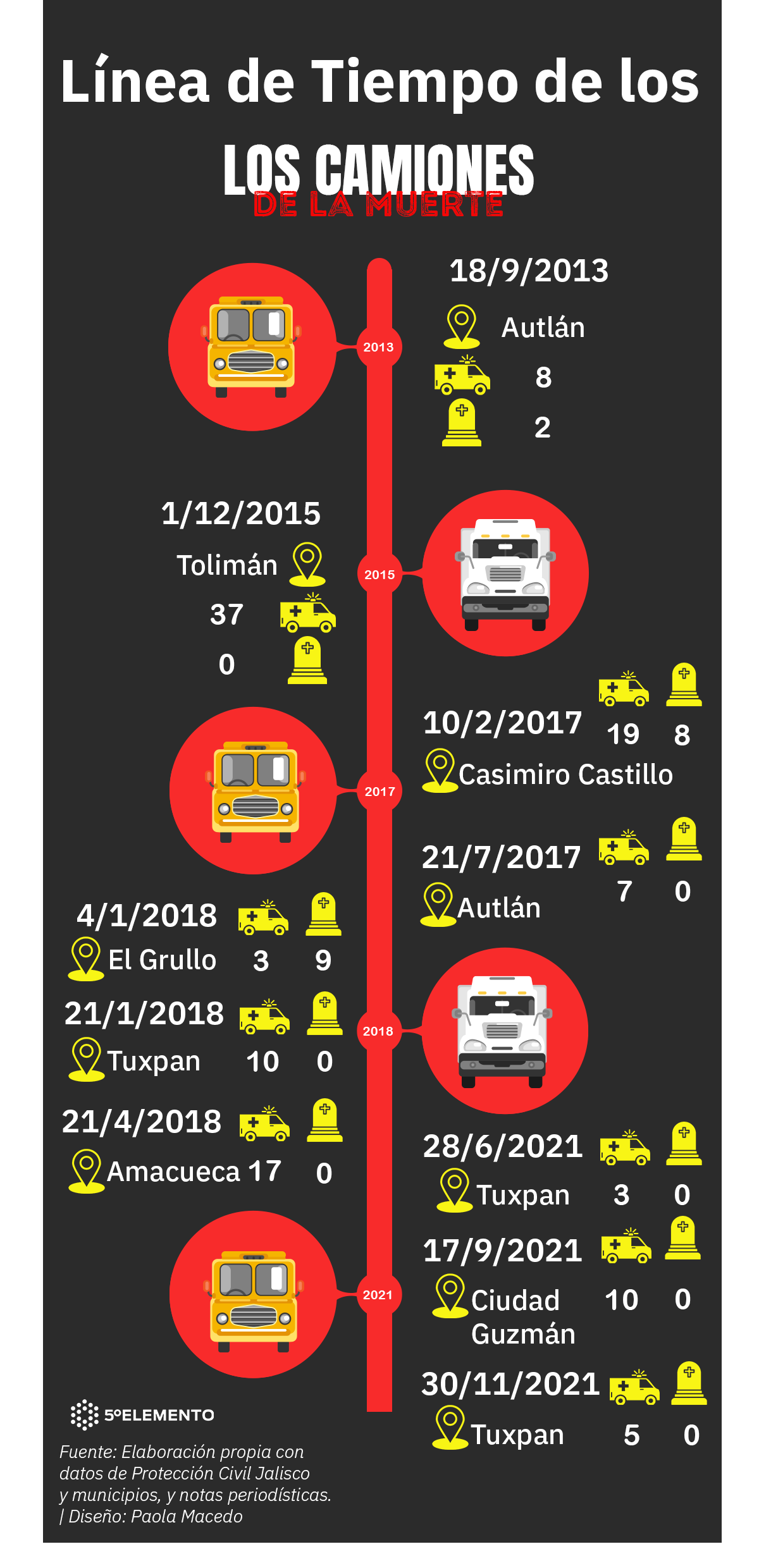

In the last ten years (from January 2013 to May 2023) in Jalisco, according to information extracted from parts of Civil Protection news from the state and municipalities, official statistics and journalistic news, at least 34 day laborers have died in accidents like this and 216 have suffered injuries, some for life. The victims were traveling in vans and buses hired by agricultural companies to transport personnel, such as 363, which has claimed the highest number of deaths.

A look at the tragedy

The truck was destroyed. Photographs from Jalisco Civil Protection show that in the back a BerryMex banner remained intact with its “hirings” advertisement invaded by smoke. Unit number 363 and license plate 412-RR-6 also remained visible.

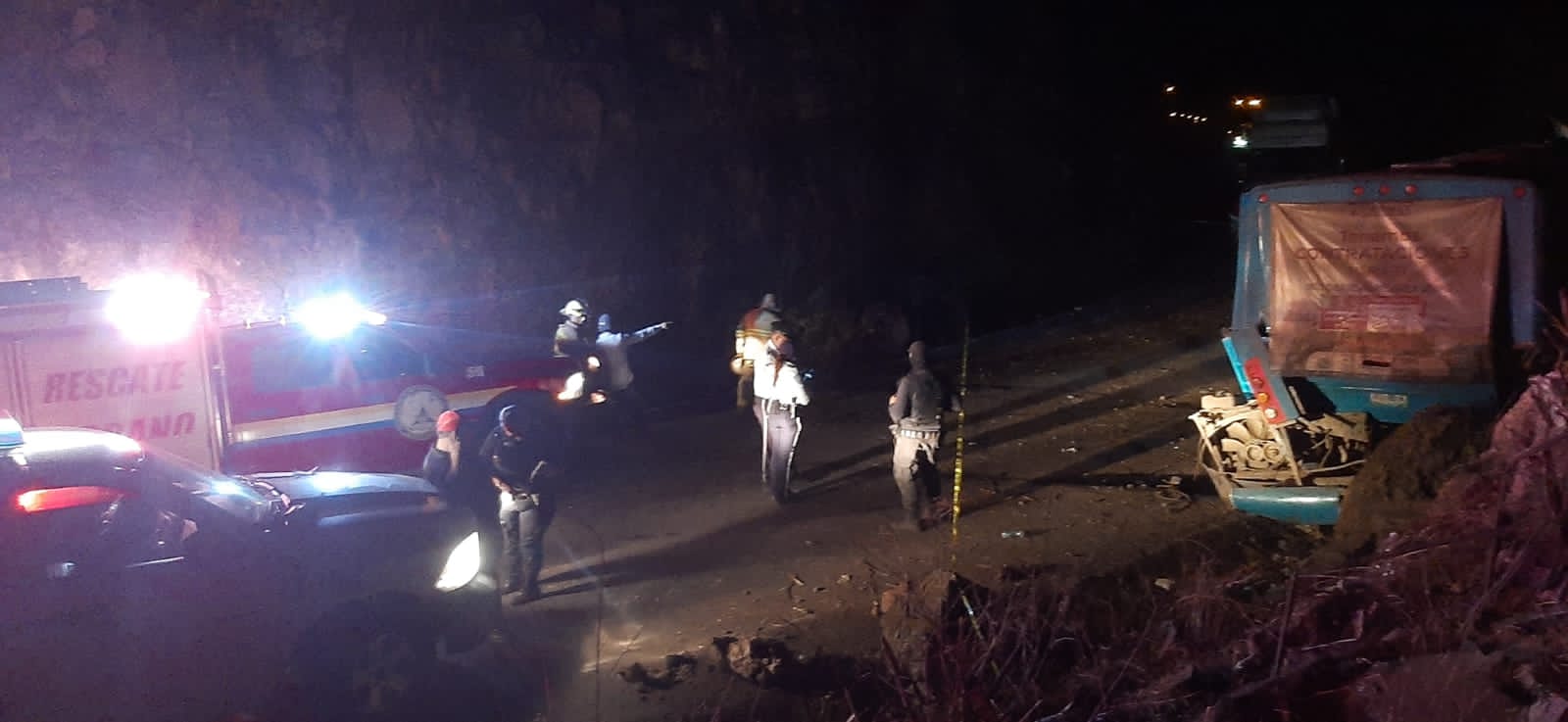

Rescuers work on the accident in which 13 day laborers lost their lives; Later, the driver died at the Jocotepec community hospital. Photography: Jalisco Civil Protection.

In the middle of the darkness, when he regained consciousness, Froilán saw that the rescuers were breaking the windows to get him out.

“I heard people crying, complaining about pain,” he says in an interview, in an effort to remember sequences from that night. “I regained consciousness for a moment from, I don’t know, adrenaline. I acted against my instincts, but then I gave up and stayed in the truck. I tried to help them [the injured]. "I didn’t even know what to do, I just felt, but there were already many people dead."

In that moment of lucidity, he felt how they took him off the destroyed bus and laid him on the ground. He was surrounded by wounded people and corpses.

The lights of the ambulance sirens illuminated the bodies lying on the asphalt; four had already been covered with blue bags.

A yellow tape delimited the scene. Two paramedics were applying cardiopulmonary resuscitation to a laborer who was lying on the floor. Less than two meters away, a bloodied companion, lying on her chassis, watched as they tried to revive her.

There were unconscious people on the floor, apparently alive, others were still trapped inside the truck while the rescuers tried to get them out.

After that moment he knew no more. He gauged the seriousness of the accident days later, in the hospital, when he watched television: the news broadcast the moment in which the paramedics loaded him unconscious into the ambulance.

Together with the rest of the survivors, they took him to the nearest hospital, the Comunitario de Jocotepec.

He woke up at the Regional General Hospital 180 of the Mexican Social Security Institute in Tlajomulco, Jalisco, where he was transferred to receive specialized care. There he asked about his relatives who were also traveling in the truck. Nobody wanted to reveal the truth to him. They told him they were taking care of them.

His wife, Miriam Ortiz Cortés, mother of Frank Irving and sister of Ariadna, moved from Pachuca, Hidalgo, upon hearing the news. When they saw each other, and she noticed that she was stable, Miriam told her that she would have to go out, she did not specify where, she did not give any explanations.

He returned to the hospital three days later. She had taken the bodies of his son and her sister to bury them in Tuxpan, Veracruz, where they were from.

Upon his return he gave Froilán the terrible news.

The “cachirul” truck

A video shot captured by the media the day after the accident shows a piece of the front of the impacted bus on the side of the road. It has a logo: a silver star on a black background, with a red circle in the center. It is the hallmark of the Brazilian brand Marcopolo buses. The word Ruza, the company hired by BerryMex to transport its personnel, was painted on the sides.

When investigating the 412-RR-6 plates of the bus, it was found that they were issued in 2015 by the Secretariat of Infrastructure, Communications and Transportation (SICT) of the federal government for a 2006 model truck of the Mercedes Benz brand — according to information obtained via transparency —and not for that Marcopolo of unknown antiquity.

This is not the only irregularity: his circulation permit was in the name of the company Transportes en Acción, not Ruza Empresas, and it was for “excursion tourism”, an activity other than personnel transportation.

Furthermore, the registration had expired on December 31, 2020, 16 months and 18 days before the incident.

In this mess the name of the Ruiz Zamora family appears as the owner of the two companies that exchange license plates and permits. The articles of incorporation of Ruza Empresas, SA de CV (created in January 1994) show that the partners are the couple formed by Ernesto Raúl Ruiz González and Aurora Zamora Hernández, along with their children Lidia, Estrella, Ernesto Gregorio, Ernesto Raúl and Nelly Ruiz Zamora.

The trade name or brand was registered with the Mexican Institute of Intellectual Property (IMPI) on July 7, 2000 - by Lilia Judith and Nelly Edith Ruiz Zamora - as Grupo Ruza.

In turn, Transportes en Acción (a company created in 2009) has another Ruiz Zamora as its main shareholder in its articles of incorporation: Alma Nallely. She also appears on LinkedIn as Director of Human Resources at Grupo Ruza.

In 2014 Lilia Judith and Nelly Edith Ruiz Zamora were appointed representatives of this second company of which Nelly Edith is also a shareholder.

Although there is no official public document that makes explicit that Transportes en Acción is also part of Grupo Ruza, Quinto Elemento Lab found that at least 12 people have shared work roles in both - from partners, legal representatives, administrators. In addition, several of its current and past workers identify themselves on Linkedin and social networks as part of “Grupo Ruza.”

Between the two companies they have at least 309 units with concessions: 194 with federal authorization, and 115 with state permit. Of the total, only eleven are in the name of Ruza Empresas, although on the streets this is the brand present on all the trucks.

José Antonio Pérez Gil, president of the Jalisco Bar Association, explains that a network of companies is frequently used to manage and obtain circulation permits, a practice that seeks to divert responsibilities or hinder the legal process in accidents like this one, in which Froilán and his family were victims.

“It does complicate [the legal process], seeing it from the point of view of the victim, who wants to seek reparation for the damage. But, in reality, the responsibility as such falls 100% on the employer, he is responsible, he has to guarantee this security to the worker, whether by subcontracting, whether by purchasing vehicles, whatever, but it must be guaranteed."

"We can’t blame the transporter and say: ’No, he told me that the truck was new, that this, that that other.’ You [employer] go against that transport company that breached the contract you made with him and the victims are going to go against you, because the person responsible is the employer, that is, you have to pay those compensations,” he says.

The lawyer summarizes the matter as follows: the employer, in this case BerryMex, is responsible for compensating workers and their families for damages suffered, regardless of the transport company.

However, relatives of the deceased and injured people affirm that what was described by the specialist was not followed; They did not receive any compensation.

On the day of the accident,

Froilán remembers that something was not looking good on May 18, the day of the tragedy.

In the morning, when he left the shelter and arrived at the stop, he realized that the transport had dropped him off along with a group of seven day laborers. The bus that always transported them had passed earlier than usual.

They called the manager, who sent the truck back to pick them up. But it was not the same unit, nor the usual driver. He missed him.

Even after the accident he connected the dots. He discovered that no one wanted to take responsibility for the damage: the vehicles that transported them were not even from BerryMex, which has its own yellow fleet, but only uses it for short trips. For periods of more than an hour and a half, like the one from Jocotepec to Mazamitla, he subcontracts to other companies.

The truck with license plate 412-RR-6 in which Froilán was traveling ended up stuck against a wall due to a brake failure, declared Francisco Javier Encarnación Morán, first operational officer of Jalisco Civil Protection, on the night of the accident.

“On the Tuxcueca cruise ship it already came without brakes and the driver chose to take the cruise ship to Citala,” he said in an interview with the media.

Arturo Hernández, the rookie driver, didn’t even have to drive that day because he had a break, but his boss asked him to replace a colleague, according to the story his mother, Hermila de los Santos, gave to the press during the wake. He orphaned a one and a half year old child.

Grupo Ruza published a statement on May 19 through its website and Facebook page in which it assured compliance with federal regulations, regretted the deaths and expressed its willingness to collaborate with the authorities. Comments were restricted in the publication.

Grupo Ruza issued a statement after the accident that occurred in Tuxcueca in which it regretted “the loss of valuable human lives.” Image: Facebook

For this investigation, Grupo Ruza’s testimony was sought on two occasions via email, and two more times by telephone call to the contact numbers that appear on its website. There was no answer.

This team of journalists went on October 17, 2023 to the company’s administrative offices, located at Anillo Periférico Poniente number 7450, municipality of Zapopan, Jalisco.

The worker who opened the door went to the Human Resources area when he was asked for an interview with one of the managers of Grupo Ruza; Upon returning, he said that the company would not talk about the accident. He added that it was a fact of the past, and the authorities had already carried out the corresponding investigations.

However, the expert reports are not public. The Jalisco Institute of Forensic Sciences refused, via transparency, to hand them over with the argument that the investigation folder, in the hands of the Jalisco State Prosecutor’s Office, is still open.

Permissive authorities

Of the 34 agricultural workers killed and 216 injured in road accidents during the last decade in Jalisco, which were transported by various companies, 14 died on May 18, 2022 in the accident of the Marcopolo bus with number 363, from Ruza .

Companies can exchange plates, use expired permits and trucks with mechanical failures because the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare (STPS) of Jalisco and the SICT of the federal government do not monitor them, they acknowledged via transparency, alleging that it is not their responsibility.

The one who does supervise them, but only on state highways, is the Ministry of Transportation (Setran) of Jalisco.

In responses delivered through public information requests and by its Social Communication area, Setran indicated that in its registry of the most sanctioned transport companies, Ruza Empresas occupies third place. Between January 2022 and March 2023, there were 18 units detained for not having valid permits or for not carrying license plates and 48 fines for speeding, driving with the doors open, the use of tinted windows, and traveling through prohibited places.

Setran reported that only between January and July 2023 it removed three units from Ruza Empresas: two because they did not have permission to circulate, and one because the license plate authorization had expired, as happened with 363, which caused the death of 14 day laborers in Tuxcueca.

Regarding Transportes en Acción, it indicated that it has not committed any infraction.

Lawyer Pérez Gil believes that accidents occur because the authorities allow companies to violate the law by not supervising them.

The solution, he clarifies in an interview, is not in reforming the laws, since they are clear. “The catalog says in the law: you have to do a, b, c. But since [me, a company,] the government does not supervise me, it is not supervising me, since corruption exists, well, things happen.”

Despite its history, Grupo Ruza has had contracts with governments via bidding and, for the most part, direct award. Among its clients are the Municipal Sports Council, in Guadalajara and Zapopan, the municipal governments of both districts, and the state government.

In May 2023, it obtained a contract by direct award with the Ministry of Education of Jalisco for almost 650 thousand pesos for the company Artificial and Human Intelligence , created by the Ruiz Zamoras in 2020, which, despite its name, also has as its activity the main personnel transportation service, in accordance with its articles of incorporation.

Through this contract, 105 Grupo Ruza trucks were rented to transport the 8 thousand people who obtained a subsidy from the DIF System (Comprehensive Family Development) Jalisco to attend the fight between boxers Saúl “el Canelo” Álvarez and John Ryder , on May 6 in Zapopan, which was sponsored by the state government and promoted by its owner, Enrique Alfaro.

A photo was published on the president’s Facebook showing the blue buses that transported the fans.

In May 2023, the Ministry of Education of Jalisco contracted, by direct award, 105 Grupo Ruza trucks to transport 8 thousand people to the fight between Canelo Álvarez and John Ryder in Zapopan. In the photo, Enrique Alfaro, governor of Jalisco. Image: Facebook

Safe transportation?

Old or damaged trucks are recognizable in the avocado and berry producing municipalities — such as Mazamitla, Jocotepec, Zapotlán el Grande, Sayula and Gómez Farías. Many are yellow and retain the word “School” on the front, because they are old school buses imported from the United States, where they had already been discarded.

Others, red or green, are trucks that previously operated in the cities of Jalisco as part of the urban public transportation system.

Between 2018 and 2023, Setran took more than 2,000 of these units older than ten years out of circulation, through a vehicle fleet renewal program. Some trucks that were saved from the scrapyard continue to circulate: they transport day laborers.

It is not uncommon for several to have fallen doors, broken windows, frames eaten away by the sun, or exhausts tied with wire that, when they advance, drag the noisy metal tubes and release dense black smoke.

Bus with 26 day laborers that, after leaving the municipality of Gómez Farías on December 16, 2022, fell into a ravine on the Sayula slope. There were 23 people injured. Photography: Jalisco Civil Protection.

Interviewed about the buses they use to transport personnel, such as the truck that transported Froilán and Abisai, Miguel Ángel Curiel Mendoza, who, in addition to directing Driscoll’s in Mexico, presides over the National Association of Berries Exporters AC (Aneberries), points out: “ From the standards of companies like BerryMex, Driscoll’s and members of Aneberries, they have to make sure that [the trucks] meet Mexican standards. “You can’t have transportation that doesn’t comply.”

—Do Mexican standards allow them to have trucks that are no longer used in the United States?

"Clear. They are not used [there] due to [lack of] efficiency in performance, mileage and so on. They are brought in, rehabilitated and meet standards. Let’s see, they have to be authorized by the Ministry of Transportation, that is, it is not something outside the regulation."

Between January 2013 and May 2023, at least ten trucks with these

characteristics were protagonists of the accidents in Jalisco. But there are also incidents in which workers were transported in cargo vans. Instead of carrying bags of fertilizer or boxes of avocados or berries, they were used to transport personnel.

They left, in total, 68 people injured and 20 dead. The name of the companies involved is not specified in the official and press reports.

The causes of the accidents are also not clarified.

However, the excess of passengers on low-speed roads is a serious problem: these vans carry between 10 and 27 day laborers in the box, according to the Jalisco Civil Protection news reports that were accessed via transparency for this investigation.

After the bus in which Froilán and Abisai’s family died, the second most serious case of the last decade occurred in the municipality of Casimiro Castillo, on the South Coast, on February 10, 2017. Eight people lost their lives—three They were girls—after the overturning of a three-ton truck in which 27 people were traveling, of which 12 were minors.

Since then, state authorities promised to strengthen surveillance of the transport of agricultural personnel, but road accidents and deaths continue.

Silence from the union

At the Aneberries International Congress, which took place in Guadalajara in July 2023, it was almost taboo to talk about the accidents suffered by day laborers on whom their earnings depend.

Interviewed for this report during the congress, Pierre Delort, representative in Mexico of the International Labor Organization (ILO), said that when the companies invited him to visit the fields of Zapotlán el Grande or Autlán, south of Jalisco, he saw new units and in good condition. He did not want to comment on the death trucks involved in the accidents.

“Safe transportation must have technical control, with as many passengers as there are seats and seat belts, with trained drivers and driver’s licenses,” he simply responded. What they have shown her falls within those parameters, she insisted.

Delort acknowledged that, in the event of accidents, the ILO does not have programs to monitor and support victims; For that, he said, unions exist.

BerryMex workers are unionized in the United May Day Unions of Workers and Employees (Súmate). When the general secretary, Gabriel Antonio Trujillo Ocampo, was sought to know how he protected his members and to know his position on the “trucks of death,” he did not respond.

The Secretary of Labor in Jalisco, Marco Valerio Pérez Gollaz (left), along with the general secretary of Súmate, Gabriel Antonio Trujillo Ocampo. Photography: Facebook of the “Súmate” union.

The Secretary of Labor and Social Welfare of Jalisco, Marco Valerio Pérez Gollaz, also refused to be interviewed for this report, although in his speech to the producers, during the 2023 Aneberries congress, he referred to the lack of security in the Shuttle service personnel.

“Another problem that we have to resolve with you is a personnel transportation protocol. As long as we make it more professional and safer for the most important thing that companies have, human capital, we will avoid these catastrophic accidents that, in many cases, occur due to distractions and lack of maintenance."

This occurs despite the fact that the Federal Labor Law (LFT), in its article 283, obliges employers to “provide workers with free, comfortable and safe transportation from living areas to workplaces and vice versa. The employer may use his own means or pay for the service so that the worker can use adequate public transportation.”

There is no justice, only impunity

The deaths of Abisai, Irving and Ariadna remain unpunished for almost two years.

The Jalisco State Prosecutor’s Office opened investigation file 2445/2022, but to date there are no sanctions for the crime of manslaughter, the illegal act that the prosecutor’s office pursues in these cases.

Lawyer Pérez Gil specifies that the only result that can be obtained from these investigations is economic reparation for the damage, because those identified as alleged culprits are legal entities (companies) and not individuals.

The families were denied a copy of the investigation folder: they were only given a letter to claim the bodies, as in the case of Miriam, Frank Irving’s mother, Froilán’s wife and Ariadna’s sister.

To find out the status of the investigation, they must go to the regional prosecutor’s office, which is an ordeal, since the victims’ relatives live in Hidalgo, Oaxaca, Veracruz, Puebla, the State of Mexico and Nayarit. And they can’t afford to miss their jobs.

A weekend before the accident occurred, Bisa had proposed to Wendy, his girlfriend. She dreamed of working abroad for a while so she could save and get married. He said that he worked at BerryMex because they promised him a visa to work with this same company in the United States or Canada; The accident ended his plans. Photography: Courtesy of family.

According to what was reported by the families, BerryMex, like Ruza Empresas, evaded responsibility for the death of their workers. To date, they have not received compensation or reparation for the damage as established by the Federal Labor Law.

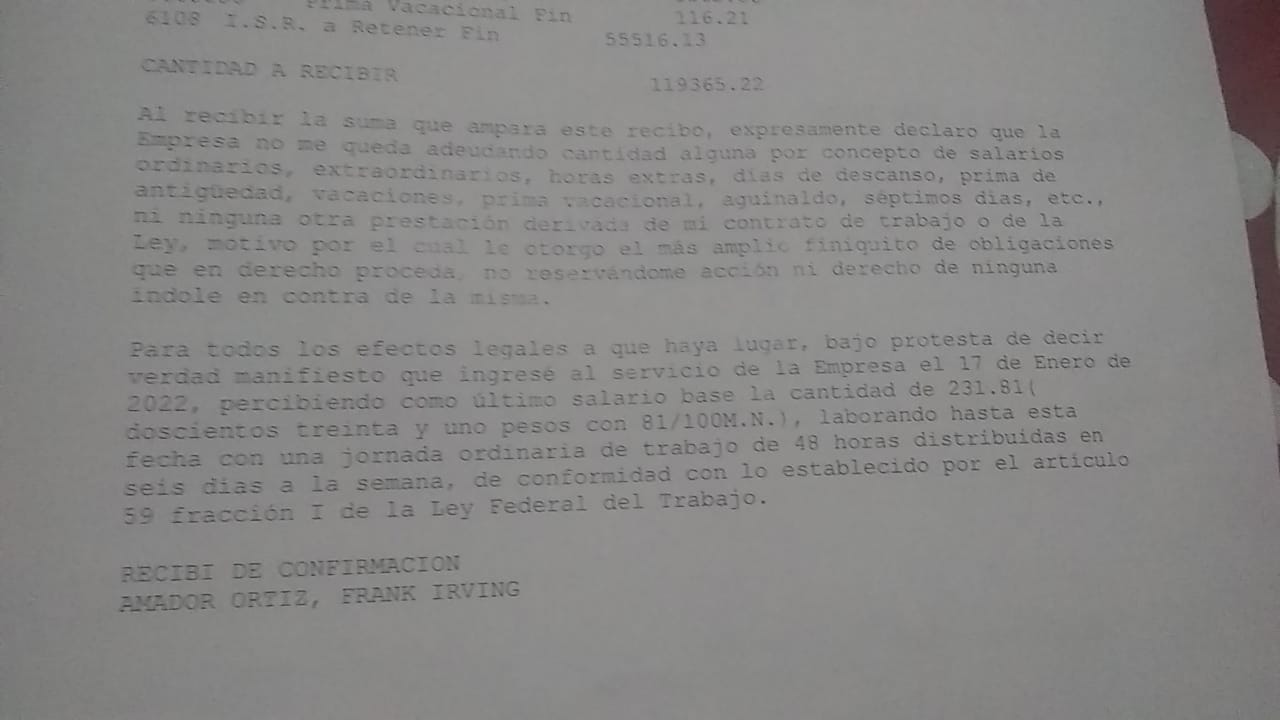

For BerryMex, the life of Irving, who was only 20 years old, had a value of 119,365.22 pesos. The company paid that as settlement.

Pérez Gil specifies that giving a severance payment – which is the amount of money that a company must pay an employee when the employment relationship ends – instead of compensation is illegal: the LFT stipulates in its article 502 that the minimum compensation is 5 thousand days of salary.

“That is what a person costs under the Federal Labor Law,” he admits.

Taking into account the legal reference, with a daily salary of 231.81 pesos, like the one Frank Irving received days before his death, his family had to be compensated with approximately one million 159 thousand 50 pesos gross, plus two months’ salary for funeral expenses. .

The settlement he received only represents 10% of what would correspond as compensation.

Miriam Ortiz, Irving’s mother, signed the settlement in the name of Frank Irving Amador Ortiz, he recalls angrily.

“They made us sign on their behalf to disclaim responsibility. Those gentlemen from BerryMex, to give me some of my son’s money, may he rest in peace, made me sign; If not, they would not give us anything to move around or for the expenses I was having with my other children. "With my husband hospitalized, taking advantage of the situation and our poverty, that’s how they played their card."

Frank Irving’s family shared the settlement document with reporters.

During the interview, Miriam’s face becomes sad, her eyes water and her voice breaks. She swallows hard to hold back her tears.

That tragic night was also different for her. She was waiting for a call from her son Frank Irving or her husband Froilán, who never came. Exhaustion overcame her and she fell asleep. When she woke up it was still early morning; She realized that she had several missed calls from Ariadne’s eldest son.

“What happened, son?”

“Auntie, I was calling him at around 3 in the morning, but he didn’t wake up.”

“No, son, I fell asleep.”

“Well, I want to tell you something, but I need you to be calm.”

“But then tell me, I won’t be calm if you don’t tell me.”

There he learned that Frank Irving and Ariadna had died in the accident and that Froilán was in serious condition in the hospital. She immediately traveled from Pachuca to Guadalajara, did the procedures to recover the bodies, consoled her nephew who also came to claim the body of her mother, and visited her husband.

“To do all that I had to break myself into a thousand pieces. My nephew went to Semefo [Forensic Medical Service] to recognize my sister and my son. "I didn’t have the courage."

Frank Irving, Froilán and Miriam Ortiz. Photography: Courtesy of the family.

After the tragedy, the international civil organization Information Center on Business and Human Rights (CIEDH) asked BerryMex and Grupo Ruza to respond to the public accusations made by the families.

BerryMex responded that “all workers affected by the unfortunate accident have the right to legal benefits, which include widowhood, orphanhood and disability pensions, as well as additional benefits and insurance provided by the company in accordance with the collective contract,” as published in the organization’s website . Grupo Ruza did not respond.

Claudia Ignacio Álvarez, researcher for Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean at CIEDH, points out in an interview that when there is a subcontracting of services such as transportation, the two companies are responsible for repairing the damage.

“Both companies must respond; “The guarantee of the adequate conditions of the units and the care insurance go through the transport company,” he states.

Pérez Gil agrees: subcontracting does not exclude BerryMex from responsibility. On the contrary, he says, if the company discovers that there are irregularities on the part of the carrier, it is obliged to report it.

BerryMex and Ruza don’t even answer Miriam’s calls anymore.

“For them, we are already forgotten. They did not even reimburse us for part of the expenses incurred; They just didn’t answer the calls anymore. They didn’t lose anything, it doesn’t hurt them, but I did lose a lot. My son had a life ahead of him, my sister was very young and she left two orphaned children.”

His family’s orphanhood and widowhood pensions, which BerryMex told the CIEDH it would deliver, remained promises.

When this team consulted relatives of the survivors who live in Hidalgo, Oaxaca, Veracruz, Puebla, State of Mexico and Nayarit, the four who responded agreed that they were not compensated or covered the cost of rehabilitation.

The injured also did not receive medical follow-up. Froilán says that companies ignored their recovery.

After being unconscious in the hospital, he woke up with a deep wound on his forehead and could not open his eyes properly because he had a piece of glass embedded in his eyeball from a window. Furthermore, she had part of her tongue detached; a fractured finger and nose, and the kneecap of a deviated knee with loss of synovial fluid.

While he was still hospitalized, his temporary contract with BerryMex ended, and the insurance expired. The company, he accuses, distanced itself from his medical condition.

Lawyer Pérez Gil specifies that what Froilán describes is another illegality. Companies should not terminate the contract of an employee who, while doing their job, is injured, and are obliged to pay salary and medical expenses, or pension in case of disability.

“[An injury after a road accident] is not a cause to terminate the contract between worker and employer, which is what normally happens. Companies say: ’Oh, no, it’s going to be more expensive, let me settle it and we’ll see you there and the problem will be over.’ As a company they have to, if necessary, maintain it, and if necessary pay the IMSS so that it is practically like a retirement, but more so due to accidents.”

This did not happen. Upon returning to Pachuca, still injured, Froilán immediately looked for work: he needed to recover his social security to take care of himself. He found work in a company that produces pork rinds.

“I get neuralgia [headaches], I hear loud noises and I get upset. I suffer from pain all over my body, my knee hurts as if I had rheumatism; I don’t walk well anymore,” she narrates. The scar on his forehead always reminds him of that May 18, 2022.

When this team of journalists sought out the Súmate union organization to find out his position, instead of agreeing, they informed BerryMex of this investigation. BerryMex, through Óscar Eduardo Olmedo, representative of the Cuadrante communication agency, sought out the journalists via email. In his message he stated that they would resolve in writing any questions sent to them. Although a questionnaire was sent to them, BerryMex’s response never came.

The ghosts of the tragedy

Almost two years after the incident there are not only physical consequences, the pain due to the absence and the disappointment due to the lack of justice and reparation for the damage also persist.

At the site of the accident haunt the ghosts of misfortune. A shredded tire on the side of the road, some discolored blue seats, a half-buried bluish-brown blanket, and, on top of it, the sole of a work boot.

On one side, a five-liter gallon and several plastic bottles. A cap with the initials “Súmate” stands out, from the union to which the workers belonged.

The metal retaining fence that bus 363 bounced off remains submerged and broken, with remains of its royal blue paint: a reminder of the first impact. The yellow tape with which they surrounded the scene remains tangled in the bushes.

View of the accident site from the opposite direction. The metal retaining fence that the truck collided with before crashing into the wall has not yet been repaired.

Before reaching the wall against which the unit crashed, three crosses commemorate the 14 lives that were lost on May 18, 2022.

Three crosses are the sign of death. BerryMex abandoned the families, although, on one of the three crosses placed at the site of the accident, a white one, the largest, pays tribute to them: “BerryMex, forever in the heart.”

The inscription recalls that the company was in charge of the safety of the deceased.

On another cross it reads: “Letting go is not saying goodbye, but thank you…”. The third, small, wooden one, is lying on a rock.

With remains of the truck, the mourners created a kind of altar between the rocks to place the candles. The glasses look broken and the wicks are extinguished.

“I do want justice to be done and for them to pay for the people who died, for the children who were orphaned, for the parents who lost their children. They [the businessmen] don’t earn five pesos and they left us with one hand in front and the other hand behind,” Miriam demands.

“Let them fix their trucks and take the units in poor condition out of circulation, so that no more innocents die. Let there no longer be incomplete families, empty chairs, due to the negligence of the owners who do not want to spend and become richer at the expense of innocent lives,” recriminates Santa, Abisai’s sister-in-law.

The huajes and tepehuajes trees that were hit by the truck have already begun to sprout and resume their path, something that the families, due to the lack of justice, cannot do